Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly

Formerly "Picture of the Month"

January-February 2017

The Magical Circle

The magic of a new beginning Happy New Year to you, welcome back.

"There

is a magic in the beginning of a new year:

it's all expectations and no regrets, as it were."

With this thought, inspired by Herman Hesse's (1986) poem Stages, I started the new year thirteen years ago (Ulrich, 2004). Unlike then, I do have some regrets to confess though: I haven't managed, as planned, to complete the final essay in the current series of explorative essays on the role of general ideas in practical reasoning, titled "The rational, the moral, and the general." I've now decided to make a virtue of necessity and prepare a brief, alternative Bimonthly page. Is there perhaps some way to connect the "magic" theme of that 2004 page with my current interest, emerging from the series on general ideas, in ancient Indian-Buddhist thought?

My idea is to offer a short introduction to the "magical circle," better known as Mandala, an age-old symbol of the unending cycle of creation and decay, of beginning and end, in the life of the cosmos as well as in our human lives. Mandalas can be seen as historically early attempts, particularly in Eastern thought but also in early American-Indian pueblo cultures and in medieval Christian spirituality (cf. Jacobi, 1973, p. 136), to come to terms with general ideas without which humanity may not be able to live and make sense of this world, ideas such as the existence and interdependence of an inner (spiritual, ideational, emotional) and an outer (social, material, phenomenal) world; the interaction of the realms of the human and of the divine; the unity of whole of the universe and its smallest parts; the world's origin and end in an all-encompassing, never diminishing source of energy and vitality; nature's unending cycle of birth and death; the creative tension between the real and the ideal; and so on. Handed down to us particularly through the Sanskrit scriptures of the Vedic, Vedanta, Buddhist, and other traditions of the East, mandalas have for some 2,500 years been an aid to meditation and reflection on such issues.

What is a mandala? The Sanskrit noun "mandala" means as much as "circle" or "whole (body)," whence it also refers to cosmological notions such as "universe" and a "collection" or "multitude" of phenomena, or the "orbit (or path) of a heavenly body," a "halo" around the sun or the moon. Further, derivative meanings are the "circumference" of a circle or globe, the "band" that connects, a "circular bandage," a "ring," "wheel" or "circular array" of something; but also a "province," "zone" or "territory," or a "surrounding district" or even "neighboring state" (see SpokenSanskrit.de dictionary, n.d.). The term also lends itself to adjectival use and then basically means "round" or "circular."

Roundness is indeed the essential leitmotif of all mandalas, whether they come in round or square form:

Roundness (the mandala motif) generally symbolizes a natural wholeness, whereas a quadrangular formation represents the realization of this in consciousness. (Franz, 1964, p. 234, with unspecific reference to Jaffé, 1964)

As an aid to meditation, mandalas come in two versions, either in graphic form as two-dimensional designs or in three-dimensional, geometrical forms. Graphic mandalas can take a square-shaped form that contains round, symmetric motifs or conversely, a round form that includes quadrangular or other geometrical shapes. Many also content themselves with circular motifs only. Common to all is a strict symmetric arrangement of all design elements around a center, toward which the beholder's contemplative, meditative or reflective endeavor will figuratively speaking be directed. Fig. 1 shows an example.

Fig. 1: Example of a graphic mandala

combining

round and other geometric forms

(Source:

Mandalas

Para Todos,

1986,

with a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 3.0 license)

The three-dimensional mandalas are made of (sometimes gold-plated) wire and (often imitated) jewels and can usually be arranged into different geometrical forms, all of which are characterized by a central, vertical axis of symmetry. Folded together they become flat and round and thus resemble the two-dimensional, graphic mandalas of the round type. The following account refers to the three-dimensional form. As it lends itself to easy rearrangement, it allows manual handling rather than mere contemplation and thus facilitates a process of exploring the associations and ideas that its different shapes may evoke.

What does a mandala "mean"? Common to all mandalas is their being seen and used as symbolic representations of the harmony and unity (or wholeness) of nature (or the cosmos) and of the flow of human life and consciousness in it. The ideas of harmony and unity come to the fore in the perfect symmetry that characterizes all ways of drawing or unfolding them. Early on these representations became an aid to mediation and reflection on the cosmological forces that shape human life, but also to getting in touch with one's inner self as the center of human awareness, balance, and spirituality.

In what follows, I take the liberty of assuming that there is no such thing as "the" meaning of mandalas. Rather, I propose to see mandalas as an invitation: an invitation, that is, to self-discovery. It is in this spirit that I will unfold and describe the mandala's different "stages," as I will call the succession of different shapes it can take, so as to remind us at all times that we are engaged in a personal process of "unfolding" what the mandala may mean to each of us as individuals, at the moment we are unfolding the specific stage considered. All I can attempt here is to give some hints at my personal way of interpreting each stage, here and now as I am writing. Some readers may be disillusioned by such restraint, but I find myself in rather good company: even C.G. Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist who first described the value of these ancient representations of wholeness for interpreting dreams and who probably has worked more intensively with mandalas than any other therapist – he is also the modern author who to my knowledge first proposed to name them "mandalas" and as such brought them to contemporary Western attention – refrained from assigning them any fixed meaning or purpose. Instead he described them in terms of a process of self-discovery and transformation, that is, of being on the way to "individuation" (i.e., finding one's inner center, the Self as distinguished from the Ego), which implies that their meaning must remain a deeply individual one and can change from day to day:

Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is: "Formation, Transformation, Eternal Mind's eternal recreation."1) … My mandalas were cryptograms concerning the state of the self which were presented anew to me each day. In them I saw the self – that is, my whole being – actively at work. To be sure, at first I could only dimly understand them.… I no longer know how many mandalas I drew at this time. There were a great many. While I was working on them, the question arose repeatedly: What is this process leading to? … I was being compelled to go through this process of the unconscious. I had to let myself be carried along by the current, without a notion of where it would lead me. [The mandala] is the path to the center, to individuation. (Jung and Jaffé, 1961, p. 196; the italics, omissions indicated by dots and addition in brackets are mine)

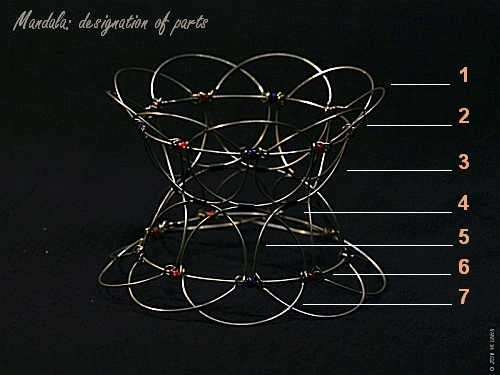

Using the mandala; designation of its parts The mandala is used by arranging it so that it takes on different shapes, one leading to the other. I understand each stage as symbolizing one of the different ways in which cosmic and personal forces shape the human condition and an individual's state of awareness. Originally there were seven or eight such stages, corresponding to the seven planets of the sun that were known in ancient times. Present-day mandalas usually comprise nine stages, which once again mirrors the nine planets of the solar system known today and moreover provides for stronger symmetry.

Below I depict these nine stages by means of conforming configurations of my personal, three-dimensional mandala, each being illustrated by a photograph. For each configuration, I'll briefly explain how it is obtained and what it symbolizes to me here and now. Readers should feel free to interpret these configurations differently, in ways that make personal sense to them. With the photographs and the associations they evoke in me, I merely hope to give an impetus for individual reflection, but not a model for their interpretation or even for their "correct" use.

In order to facilitate a systematic description of the handling of the mandala, here is a short definition of its parts:

|---------------- diameter approx. 10 cm ----------------|

Designations:

1 / 7 = outer wreaths (1 = upper, 7 = lower)

2 / 6 = constant circles or rings (2 = upper, 6 = lower)

3 / 5 = inner wreaths (3 = upper, 5 = lower)

4 = center = central circle

|

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

The nine stages: unfolding the mandala Corresponding to the fact that in ancient times, the solar system served as a basic cosmic model and inspiration and was also taken to be in the center of the universe, the mandala starts with the sun as its first stage and puts it in the center. Given its "central" importance, I will dedicate a bit more space to this first stage than to the later ones. So do not worry if the account that separates the second from the first stage should look overly long to you; the subsequent accounts will be shorter.

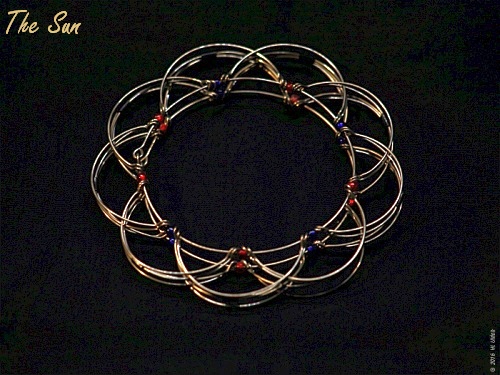

THE SUN

In the "Sun" position, the mandala is still closed. That is, it remains two- rather than three-dimensional. In this stage, it strikes me as a perfect symbol of completeness, roundness, wholeness. It is perfect, yet as a three-dimensional structure that is still folded together it allows of development and growth. It is potential as much as perfection. It is a beginning, with all the magic that accompanies every beginning:

There is a magic inherent in every new beginning, protecting us and helping us to live. (Hesse, 1986, p. 199; my transl.)

More specifically, as a metaphor of the cosmic order and particularly of the solar system, this initial stage of the unfolding process may be understood to symbolize the most fundamental beginning one can think of, I mean the central role of the sun as origin of all energy, movement, and life. The sun is such an important source of energy and life in this world of ours that it appears natural to give it a central place. If the sun did not exist, we would have to invent it for a perfect world!

A similarly central place in our lives belongs to our innermost Self, our soul (not to be confused with the Ego). It supplies the other major reference point of our lives, of learning to understand who we are and what to make of our time in this world. Accordingly important, but also difficult, is the effort of "finding oneself," that is, developing a fuller awareness of what moves us and what impedes us in becoming what we have the potential to be. This observation suggest to me that the "sun" configuration may also be understood to symbolize our individual quest for wholeness or completeness, for growth, for being alive and enlightened. Indeed, this is a perspective that became central to C.G. Jung's already mentioned notion of a "process of individuation" (see, e.g., Jung, 1961 and Jaffé, 1961; Jung et al., 1964; Franz, 1964; Jacobi, 1973), in which the use of mandalas does play an important role.

But of course, as already the name of this basic configuration of the mandala suggests, its basic reading is probably metaphysical rather than psychological. It then stands for the "cosmological" idea of an infinite universe, as the epitome (or embodiment) of the totality of conditions that rule our lives. At the same time, I am tempted to see in the mandala's "sun" stage not only a reference to the largest conceivable object of thought, the universe, but also to its smallest building stone, which for a long time in mankind's history of ideas was thought to be the atom. The photograph above strikingly reminds of the image of an atomic nucleus with its electrons (i.e., protons and neutrons) circulating around it. Thus seen, the mandala beautifully unites the largest and the smallest aspects of the universe of which human thought could conceive at the time.

This is the more remarkable as the old sages, for example, in the Upanishads, were very much aware of the fact that we may never be able to fully grasp and know these opposite, ultimate aspects of the universe – the infinitesimally small and the infinitely big or whole. I therefore tend to see in the mandala not only a metaphysical metaphor of the universe but equally an epistemological notion of the challenges and limits that human inquiry faces in the quest for valid knowledge and thought about the world, as well as for proper conduct of our lives in it.

I have spoken above of the "cosmological" idea of a universe. But mind you, the cosmological idea matters not only for astronomers but for all our daily thought and action. The category of the universal is more fundamental to our thought and knowledge than we usually assume. It is indeed present in all the particular ideas, images and concepts that we have or make ourselves of the concrete phenomena that surround us; for we can really understand the particular (or concrete) – and see just how particular it is – only as distinguished from the universal (or general). Consequently the opposition, and indeed the tension, between the particular and the universal is always also present in the ways we speak and argue about things. Whether we are aware of it or not, all thought and argument moves within a "universe of discourse," a universe that will usually be conditioned by particular no less than by truly universalizable views and values. To what extent it is so conditioned, we can "comprehend" only against the notion of an unconditioned whole as an indispensable critical idea of reason.

In the terms of my current series of essays on the role of general ideas, we encounter here the two fundamental limiting concepts of all metaphysical, epistemological, and moral reflection, the concepts of the particular and the universal, united in an integrative symbol of the universe and of all human awareness of it. Limiting concepts orient our thought and as such are indispensable for critical reasoning, but we should not take them for possible objects of knowledge.2)

As a final, related consideration, an association with Kant's transcendental philosophy offers itself to me here. As he taught us, any totality of conditions that can sufficiently explain a phenomenon or circumstance of interest is itself absolute, as outside it there are, by definition, no further relevant conditions. If this were not so, the totality of relevant conditions would still depend on some external conditions and thus would not embody the "whole series of conditions" required for really explaining anything, and certainly (as an ultimate limiting concept) the universe. A totality of conditions is necessarily unconditioned, that is, complete in an absolute sense:

The transcendental concept of reason is, therefore, none other than the concept of the totality of the conditions for any given conditioned. Now since it is the unconditioned alone which makes possible the totality of conditions, and conversely, the totality of conditions is always itself unconditioned, a pure concept [read: an idea] of reason can in general be explained by the concept of the unconditioned, conceived as containing a ground of the synthesis of the conditioned. (Kant, 1787, B379, similarly B444f; my italics and brackets)

In simpler terms: to explain anything seriously, reason has no choice but to consider the totality of relevant conditions; but since the totality of conditions is by definition unconditioned, that is, absolute, it lies beyond the reach of human knowledge. This consideration is indeed fundamental to a critical concept of reasoning. It tells us that whenever we claim (or tacitly assume) to have sufficient reasons for a theoretical or practical assertion – a judgment of "fact" or "value" – we risk claiming more than what we can justify. We tend to presuppose a comprehensiveness of knowledge that is not normally achievable to us. This is why it is so easy – and frequent – for all of us to claim too much! Just listen to people on the bus and you know what I mean (for a full account, you may want to read Ulrich, 2000).

THE SKY

Things begin to move now; we begin to unfold the mandala. Its second position is obtained by lifting the upper outer wreath (cf. the explanatory photograph above) and then turning it inside (i.e., towards the mandala's central vertical axis) until it is nearly closed. All other parts remain in their folded, flat position. The result should look approximately as follows:

In this "Sky" position, the mandala symbolizes the dome of the sky. The sky in turn stands for the heavenly side of our earthly existence and for all we may associate with this notion: hope and faith; redemption from material needs and deprivation; or, in the Vedic and Upanishadic tradition as well as in other traditions of Eastern spirituality, notably in Buddhism, Jainism, and medieval and contemporary Hindu philosophy, the eventual liberation (moksha in Hinduism, nirvana in Buddhism) from the perpetual cycle of rebirth and transmigration of souls (samsara).

In short – and I want to keep my promise and be short – the sky dome is traditionally understood as a symbol of liberation from all tribulations of earthly existence, and thus of infinite freedom and spiritual fulfillment. But it remains of course to you to find out what needs and chances for liberation you want to associate with this stage of the mandala. My own main interest here is in associating "liberation" with the redemption and/or critical handling of claims in practical thought and action, in particular in moral reasoning. Liberation in this context means for me a self-reflective effort of freeing my professional and personal practice from the eternal trap of claiming too much. To be sure, it's a kind of liberation (or better, of reflective practice) that I can only hope to achieve so far but never completely. In the terms of my mentioned series of essays, it is bound to remain a mere "approximation." Motto: The sky is the limit – that is, we can always try better.

THE EARTH

The third position of the mandala results from lowering and then closing the lower wreath, analogously to the way in which the upper wreath was previously lifted and closed.

In the "Earth" position, the mandala symbolizes the unity of heaven and earth; of the spiritual and the material world; of general ideas and particular phenomena. It creates an inner space that may also be seen to stand for the unity of the individual self (or atman, in the Upanishadic tradition) and the universal whole of cosmic reality (brahman). It might thus be understood to symbolize a space for personal growth on the way towards finding a proper balance between material and spiritual needs; between pragmatic action and remaining faithful to one's deepest ideas. It is, then, about achieving adequate pragmatic performance (Dash, 2001) in this multifaceted and imperfect world of ours, while still cultivating our innermost sense of self, that is, developing an adequate sense of identity (who we are as persons) and of self-fulfillment (how we may become what we have the potential to become).

THE EGG

The forth, "Egg" position of the mandala is achieved by grasping the earth-shaped mandala at the two outer wreaths (one hand holding the lower, the other the upper wreath) and then pulling them out carefully, making sure they remain closed and the central circle still stands out like in the "Earth" position, so as to achieve the oval shape of an egg rather than the round shape of a globe.

The "Egg" position is obviously an age-old symbol of fertility. As a stage in unfolding the mandala, we may understand it as a metaphor for individual or collective growth. I tend to understand "growth" here in a wide sense that includes everything that moves us towards becoming what we have the potential to be. How can we prepare the ground for such a process of becoming (see, e.g., Allport, 1955; Rogers, 1961)? Aspects of material (biological, economic, ecological, etc.), spiritual (emotional, intellectual, artistic, expressive, reflective, etc.) and societal (cultural, ethical, moral, political, aesthetic, etc.) development and creativity may be involved, with a view to one's own current needs as well as those of others.

My own preferred way of reflecting on my personal quest for growth is in terms of C.G. Jung's already mentioned "process of individuation" (Jung and Jaffé, 1961; Jung et al., 1964; Franz, 1964; Jacobi, 1973), as well as of Kant's eternally challenging call to striving for individual autonomy, maturity, and "good will," along with his concepts of "enlarged thought" and "consistent reasoning" (Kant, 1784, 1786, and 1793, as cited and discussed in Ulrich, 2009, esp. pp. 8-15).

THE UNIVERSE

The fifth, "Universe" position of the mandala is reached by pulling the two outer wreaths a bit further out, until a nicely round or slightly higher than wide globe or sphere results.

This globe shape, as shown in the photograph, represents the cosmos and as such should not be confused with the previous "Earth" stage. It might have us think about the origin and interconnected nature of the world in which we live, and about our place in it. What is real, what imagined? What should and what can we do? Who am I, and what is the meaning of it all?

This is the sort of themes the "Universe" shape of the mandala may suggest to us. It is the shape with which the mandala reaches its full size, and accordingly it suggests "big" and far-reaching questions; questions that point beyond the limits of what we can (claim to) know or achieve through our actions. From a Kantian perspective, I tend to associate with it a methodological and practical-philosophical intent; it then asks us to carefully consider the entirety of conditions and consequences on which the adequacy of our ways of acting depends. And since only gods and heroes achieve comprehensive thought and knowledge, we have to ask ourselves: In what ways may we fail to consider all relevant conditions and consequences? How "rational" can our practice consequently be said to be, and what does it contribute to "improvement"?

Such thoughts might in turn prompt us to review the views and values that make up our universe of discourse (or of thought and action) in specific contexts of (professional or everyday) intervention and decision-making. Compare the earlier, related discussion of the category of the universal in connection with the "Sun" position.

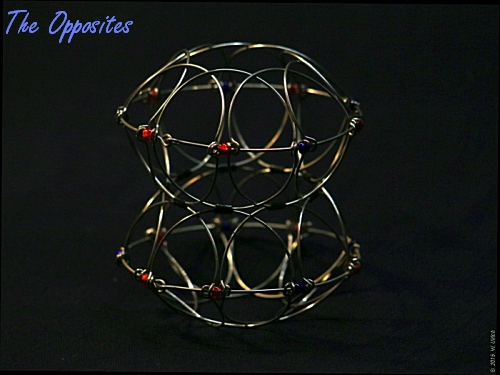

THE OPPOSITES

To go to the sixth position, the "Opposites," we now push the mandala's central circle about halfway towards the centre (the imagined central vertical axis), as if to give the previous globe shape a smaller waist size.

We thus get a double-sphere shape that symbolizes the Yin and Yang principle of Eastern thought and spirituality – the idea that all reality, and all proper reasoning about it, moves in-between pairs of opposites such a male and female, earth and heaven, light and night, the full and the void, the real and the ideal, the particular and the general, bounded and unbounded systems thinking, theory and practice, and so on. In my recent study of ancient Indian ideas, interesting new pairs of opposites have emerged that stand for complementarities such as "this" and "that" reality (or the inextricable link between experiential and ideational aspects of knowledge), paravidya and aparavidya (or the complementary search for "higher" and "lower" knowledge), atmavidya and brahmavidya (or the interdependent quest for understanding oneself and external reality), first- and second-order knowledge (or object- and meta-levels of thought and knowledge), unity and diversity (or the search for unity in diversity), and so on.

To be sure, these are mere examples of current personal interest. You should focus on whatever pair(s) of opposites that appear especially relevant to you in a situation of present concern. In my case, if there is a basic shared concern in my attempts to get inspiration or impetus for thought from the mandala, it probably is a mainly epistemological and methodological interest in the role of opposites rather than, say, a mainly metaphysical, psychological, or "spiritual" interest. As I realize with hindsight, this interest was already strong in my early work on critical systems heuristics (CSH), where I pursued it under headings such as the needs for "maintaining the contradiction" and for cultivating a "process of unfolding the reason-practice dialectic" (see Ulrich, 1983, pp. 275-314). More recently I have renewed and expanded this interest by trying to integrate ancient Indian thought, as described above, in my quest for understanding the role of general ideas in good research and professional practice, ideas such as the systems idea, the moral idea, and the idea of bringing more "reason" (or rationality) into human practice. The emerging outcome is a new focus on what I call "critical contextualization," that is, a reflective handling of the eternal tension of contextualizing and universalizing movements of thought in all inquiry and practice (see, e.g., Ulrich, 2014b, 2015, and 2016).

Generally speaking, I would suggest that the mandala's strongly symmetric design, and the sense of order and harmony thus expressed, translate into a quest for synthesis. The aim as I see it is to understand the interdependent and complementary nature and roles of chosen opposites or, practically speaking, the ways in which opposing concerns, ideas, or forces can be brought to work together so as to produce a stronger synthesis or integrated whole. In my personal view, "synthesis" as the mandala intends it is not, however, directed at making the opposites in question vanish; rather, a meaningful aim is to unfold and better understand the tension in question so as to handle it in reflecting and productive ways.

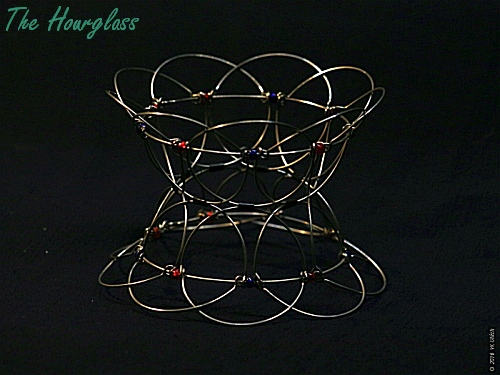

THE HOURGLASS

The next, seventh stage of the unfolding process is reached by opening the two outer wreaths symmetrically, so that one can imagine the resulting shape to represent an hourglass.

The "Hourglass" shape represents time as a movement that leads from the upper glass (standing for the past, as it were) to the lower glass (the future). The process is unstoppable and irreversible, thus symbolizing the continuous passing of time. However, as the mandala's circular structure reminds us, time also manifests itself in a cyclical nature of all worldly phenomena. As cosmological time passes, the worldly phenomena we know and cling to come and go, pass away and return. We find this eternal coming and going of things everywhere, in the endless cycle of birth and death, of growth and decay, of samsara (transmigration of souls) and moksha (release from the perpetual cycle of death and rebirth), in the history of human ideas, in art and fashion, and so on.

Practically speaking – imagining this mandala's use as a sand timer – we might be prompted to ask ourselves how we could best use the time that remains until the upper glass is empty, that is, how we should cope with the fact that in most human endeavors, time is a precious and scarce resource – a resource that, once it's gone, we cannot get back. The infinity of the universe and the finite nature of all human experience and control of time: a striking contrast that certainly can inspire many deep and moving thoughts.

THE WHEEL

The previous, hourglass shape of the mandala might prompt us to go back to the Opposites (stage 6) as well as to move forward to the Wheel (stage 8). Unfolding the mandala can be an iterative rather than a linear process. But for the sake of order, I suggest we now open the two outer wreaths fully and then turn them down (in the case of the upper wreath) and up (the lower wreath) towards the central circle, until a wheel or wheel rim emerges.

The "Wheel" shape is the perfect metaphor for perpetual motion. Unlike the hourglass, however, a wheel offers us some control, in that we can accelerate or slow down the motion by increasing or reducing the wheel's speed of rotation and can also change its direction. Again we thus have reasons to engage in reflection: How fast do we want the wheel of our life and undertakings to turn? And in what direction should we steer it?

The wheel (in Sanskrit: chakra) is in all Eastern traditions an important symbol of the spiritual transformation one can achieve through discipline, meditation, and a virtuous conduct of life. It is most important, however, in the Buddhist tradition, where it represents the teachings of Siddharta Buddha or, more accurately, the so-called wheel of the dharma. The Sanskrit noun dharma is an important and complex concept that has many meanings. In essence it refers to a practice that according to religious rule or traditional order is to be observed, as well as to the quality or virtue with which it is exercised and to the merits resulting from such exercise:

Dharma, -as, -am, m. [masculine] n. [noun] (rarely n.[neuter], "that which is to be held fast or kept, [e.g., an order,] ordinance, statute, law, usage, practice, custom"; [more abstractly also standing for] "customary observance [of caste, religious practice, etc.]; [hence also] "religion, piety; prescribed course of conduct, duty, ...; right, justice, equity, anything right, proper, or just; virtue, morality, morals, merit, good works; nature, character," [etc.]. (Monier-Williams, 1872, p. 449-c; cf. Monier-Williams et al., 1899, p. 510,3; SpokenSanskrit.de, n.d., entry "dharma" [additions in brackets are mine]).

By turning the wheel of dharma, we can – according to the Buddha's teaching – transform our destiny and gain liberation from samsara, the eternal cycle of death and rebirth. The wheel thus symbolizes the path to nirvana. The Sanskrit noun nirvana originally means "being out of a wood or in the open country" (Monier-Williams, 1872, p. 500-b; or 1899, pp. 542,1); hence, figuratively used as in the Buddhist tradition, also "cessation [of worldly existence, passions, suffering]," "emptiness [of mind]," "extinction [of the flame of life]," "salvation [from samsara]," "freedom," and so on (cf. 1899, p. 557,3, my brackets). It thus stands for the vision of final liberation and for the perfect inner peace and calm that the Buddha's path to nirvana brings. This path, to be sure, consists in following the Buddha's teaching or, figuratively speaking, turning the wheel of one's life.3) How might you try to turn the wheel of your life next? What might be your personal path to nirvana?

THE VOID

The ninth, "Void" position of the mandala comes about by pushing out the central circle so that it is in a strait vertical line with the two constant rings (which now form the mandala's outer rings) and all the wreaths (the outer wreaths folded outside on top of the inner wreaths). In other words, the mandala now looks like a wheel without wheel rim.

The "Void" is what remains after a whole cycle of the wheel of life or of the universe has been completed: an empty space with which a new chance for creation and unfolding opens up. A new cosmic or biological cycle, a new process of personal growth, a new universe of discourse can begin. This is expressed by the option of moving the two constant rings closer together until the Void is transformed back into the Sun, with which it all began (see this Bimonthly's main picture below).

The magical circle is completed, a new cycle can begin. I am again reminded of Herman Hesse's (1986, p. 199f) poem Stufen (stages), from which thirteen years ago, in that Bimonthly of January 2004 mentioned at the outset, I cited these two beautiful lines:

"There

is a magic inherent in every new beginning,

protecting us and

helping us to live.”

The magic of a new beginning can unfold.

Notes

1) [Goethe's ] Faust, Part Two, transl. by Philip Wayne (Harmondsworth, England, Penguin Books Ltd., 1959), p. 79. [Note by C.G. Jung added to the quoted text]. [BACK]

2) I have discussed the notion and importance of limiting concepts on various occasions. See, e.g., Ulrich, 2006, pp. 58-73, and 2009, pp. 13f, 22f, 31. More recently, within the current series of explorative essays on the role of general ideas, see Ulrich, 2014a, pp. 7, 13n; 2014b, pp. 20-28, 33; 2015, pp. 18f, 37; and 2016, pp. 4, 9, 13, 19, 31, and 36n. [BACK]

3) If you'd like to understand, without engaging in a scholarly study of the ancient sources, why the Buddha's path to nirvana – counter to what one might expect – led him "out of the wood" (the traditional metaphor for places of withdrawal and meditation, to which Gautama Buddha had originally withdrawn, as had countless Upanishadic sages before him), you may wish to read Hermann Hesse's (2008) beautiful novel Siddharta. [BACK]

References

Allport, G.W. (1955). Becoming: Basic Considerations for a Psychology of Personality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Dash, J. (2011). In quest of excellence: the problem of predication. Acarya Sankara's analysis of the Gita. Indian Journal of Analytic Philosophy, 5, No. 1, pp. 113-128.

Franz, M.L. (1964). The process of individuation. In C.G. Jung et al. (eds.), Man and His Symbols, London: Aldus Books, pp. 157-254.

Hesse, H. (1986). Jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne: Lebensstufen. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1986 (orig. 1942). The poem "Stufen" is found on p. 199f, the cited two lines are on p. 199; the English transl. is my own. (N.B.: Hesse also embedded the poem in his novel Glasperlenspiel (1943), an English transl. of which is The Glass Bead Game, transl., by R. and C. Winston, London: Random House / Vintage, 2000 (orig. 1970), p. 421. The two lines I have used are also cited on pp. 351 and 421. The Winston transl. reads as follows: "In all beginnings dwells a magic force / for guarding us and helping us to live.")

Hesse, H. (2008). Siddharta. Transl. from the German by Hilda Rosner. With an introduction by Paulo Coelho. London and New York: Penguin Classics (German orig. 1922; first Engl. transl. 1954).

Jacobi, J. (1973). The Psychology of C.G. Jung: An Introduction with Illustrations. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press (orig. German edn.: Die Psychologie von C.G. Jung, Zurich, Switzerland: Rascher, 1940; orig. English edn.: London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1942, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1943).

Jaffé, A. (1964). Symbolism in the visual arts. In C.G. Jung et al. (eds.), Man and His Symbols, London: Aldus Books, pp. 255-322.

Jung, C.G. (author), and Jaffé, A. (ed.) (1961). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House (Vintage Books edn., 1989).

Jung, C.G., Franz, M.L., and Freeman, J. (eds.) (1964). Man and His Symbols. London: Aldus Books.

Kant,

I. (1784). What is enlightenment? Orig.: Beantwortung der Frage:

Was ist Aufklärung? Berlinische Monatszeitschrift, VI, December,

pp. 481-494. Reprinted in: W. Weischedel (ed.): Werkausgabe Vol.

XI, Schriften zur Anthropologie, Geschichtsphilosophie, Politik

und Pädagogik 1, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp 1977, pp.

51-61. English transl. in L.W. Beck (ed.), Kant’s Critique of Practical

Reason and Other Writings in Moral Philosophy, Chicago, IL: Chicago

University Press, 1949, pp. 286-292.

[HTML] http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/kant-whatis.html

Kant I. (1786). What does it mean to orient oneself in thinking? Orig: Was heisst: sich im Denken orientieren? Berlinische Monatsschrift, VIII, October, pp. 304-330. Reprinted in: W. Weischedel (ed.), Werkausgabe Vol. V, Schriften zur Metaphysik und Logik 1, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp 1977, pp. 267-330.

Kant, I. (1787). Critique of Pure Reason. 2nd edn. [B] (1st edn. [A] 1781). Transl. by N.K. Smith. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1965 (orig. Macmillan, New York, 1929). German orig.: Kritik der reinen Vernunft, 1st edn. [A] 1781, 2nd edn. [B] 1787, in: W. Weischedel (ed.), Werkausgabe Vols. III and IV, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp 1977.

Kant I. (1793). Critique of Judgment. 2nd ed. [B] (1st ed. [A] 1790). Transl. by T.H. Bernard. New York: Hafner, 1951. German orig.: Kritik der Urteilskraft, in: W. Weischedel (ed.), Werkausgabe Vol. X, Kritik der Urteilskraft, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1977.

Mandalas

para Todos (2016). Mandalas para pintar o colorear. [A site

that offers graphic mandalas for download with a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) license.]

[HTML] http://www.mandalasparatodos.com.ar

(for the mandalas)

[HTML] http://www.mandalasparatodos.com.ar/61/Mandala-para-la-Gratitud

(for the specific mandala shown in Fig. 1)

[HTML] https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

(for the license)

Monier-Williams, M. (1872). A

Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Rev. edn.

1899. (Note; the standard edn. now used is the 1899 edn., cited

below and in the text as Monier-Williams, M. (1899.)

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/MW72Scan/2014/web/index.php

Monier-Williams, M. (1899). A Sanskrit-English

Dictionary. Etymologically

and Philologically Arranged, with Special Reference to Cognate

Indo-European Languages, rev. edn., Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press. (Orig. edn. Oxford, UK, Oxford University Press, 1872;

reprint edn., Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press /Clarendon

Press, 1951; "Greatly

enlarged and improved edn.," Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press,

1960, and Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1995).

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/MWScan/2014/web/index.php

(2014 edn.)

[HTML]

https://archive.org/stream/sanskritenglishd00moniuoft#page/n3/mode/2up

(facsimile of enlarged 1960 edn.)

[HTML] http://lexica.indica-et-buddhica.org/dict/lexica

(online search tool)

Rogers, C.R. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

SpokenSanskrit.de (n.d.). Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary.

Sanskrit to English and English to Sanskrit online dictionary

and transliteration.

[HTML] www.spokensanskrit.de/

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt. Pb. reprint edn. Chichester, UK, and New York: Wiley, 1994.

Ulrich, W. (2000).

Reflective practice in the civil society: the contribution of critically

systemic thinking. Reflective Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713693151

(restricted access)

[HTML] http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/713693151

(restricted

access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2000a.pdf

(prepublication version; also accessible via http://wulrich.com/downloads.html

)

Ulrich, W. (2004). The magic of a new beginning.

Picture of the Month, January 2004. [HTML] http://wulrich.com/picture_january2004.html

Ulrich, W. (2006). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics. In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business Ethics, Vol. I, Oxford, UK, and Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang Academic Publishers, 2006, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich,

W. (2009). Reflections on reflective practice (5/7): Practical reason

and rational ethics: Kant. Ulrich's Bimonthly, March-April

2009.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2009.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2009.pdf

Ulrich, W.

(2014a). The rational,

the moral, and the general: an exploration. Part 2: Kant's ideas of reason.

Ulrich's Bimonthly, January-February 2014.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2014.html

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_january2014.pdf

Ulrich, W. (2014b). The

rational, the moral, and the general: an exploration. Part 3: Approximating

ideas – towards critical contextualism. Ulrich's Bimonthly, July-August

2014.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_july2014.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_july2014.pdf

Ulrich, W. (2015). The

rational, the moral, and the general: an exploration. Part 5

(revised): Ideas in ancient

Indian thought / Analysis. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, May-June 2015.

[HTML]

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2015.html

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_may2015.pdf

Ulrich, W.

(2016). The rational,

the moral, and the general: an exploration. Part 7: Critical contextualization.

Ulrich's Bimonthly, November-December 2016.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2016.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_november2016.pdf

|

January 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

February 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Picture data Digital photograph taken on 26 December 2016 at 9:00 a.m. ISO 8000, no flash, exposure mode aperture priority with aperture f/5.6 and exposure time 1/160 seconds, exposure bias -0.67. Metering center-weighted average, contrast low, saturation high, sharpness low. Focal length 155 mm (equivalent to 155 mm with a conventional 35 mm camera). Original resolution 5472 × 3648 pixels; current resolution 700 x 525 pixels, compressed to 167 KB.

„There is a magic

inherent in every new beginning,

protecting us and helping us to

live.”

„Und jedem Anfang wohnt ein Zauber inne,

der uns beschützt und der uns hilft zu

leben.”

From Hermann Hesse's poem "Stufen" (Stages), 1942, cited in Hesse (1986, p. 199; my transl.)

|

Personal

notes: Write

down your thoughts before you forget them! |

|

Last

updated 5 Jan 2017

(first published 1 Jan 2017)

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2017.html