|

|

|

The

true system, the real system, is our present construction of

systematic thought itself, rationality itself.… There's so much

talk about the system. And so little understanding. (Robert

M.

Pirsig, Zen or the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, 1975,

p. 94)

"The

system," our construction of rationality

In his novel Zen and the Art of Motorcycle

Maintenance, Pirsig (1975) explains to his son Chris what

it means to maintain a motorcycle. The key is to see the technological

artifacts and systems that surround us as ideas rather

than objects. A motorcycle consists of parts made of metal,

yes; but whether and how well it works depends on the understanding

and care that flow into its construction and maintenance. The

true system we call "motorcycle" is really a system

of concepts – a mental construct – worked out in steel:

That's

all the motorcycle is, a system of concepts worked out in steel.

There's no part in it, no shape in it, that is not out of someone's

mind.… I've noticed that people who have never worked with steel

have trouble seeing this – that the motorcycle is primarily

a mental phenomenon. They associate metal with given shapes

– pipes, rods, girders, tools, parts – all of them fixed and

inviolable, and think of it as primarily physical. But the person

who does machining or foundry work or forge work or welding

sees "steel" as having no shape at all. Steel can

be any shape you want if you are skilled enough, and any shape

but the one you want if you are not. Shapes, like this

tappet,

are what you arrive at, what you give to the steel. Steel

has no more shape than this old pile of dirt on the engine here.

These shapes are all out of someone's mind. That's important

to see. The steel? Hell, even the steel is out of someone's

mind. There's no steel in nature. Anyone from the Bronze Age

could have told you that. All nature has is a potential

for steel. There's nothing else there. But what's "potential"? That's also in

someone's mind!… Ghosts. (Pirsig, 1974, p. 94f)

The

"ghosts" to which Pirsig refers at the end of this

short extract are the ghosts of

rationality, rationalities that we construct ourselves in our

minds by the way we conceive of the "systems" that

surround us – not only those worked out in steel but

also the institutions and governance systems by which we run

our societies. The rationality of systems lies in the minds

of those who design and control them. Due to the subjective and often self-serving

nature of such rationalities, they risk leading us away from

true knowledge and understanding and thus also from true rationality

and improvement of practice. This kind of alienation

of prevalent notions of rationality from people's experience

and needs is what ordinary citizens mean when they

refer to the responsible instances and administrative structures

of their societies as "the system" – the impoverished

constructions of rationality they see embodied in these instances

and structures and which are not really connected with their

own experiences, needs, and hopes, yet shape their everyday

reality. "The

true system," as Pirsig (1975, p. 94) puts it in the

motto cited at the outset, "is our present construction

of systematic thought itself, rationality itself."

The

reference systems of which we speak in boundary critique

are ideal-typical reconstructions of such rationality perspectives.

They are "ideal-typical" in that they

hardly ever occur empirically in pure form; rather, they shape

real-world practice in constantly changing combinations and situational adaptations. They can help us understand the rationality

perspectives that inform claims to relevant knowledge and rational

action. In what ways are such claims selective as to

the facts and values they consider relevant, and partial

as to the parties that are likely to benefit?

Critical

systems thinking Systems

thinking has long assumed that taking a "systems approach"

– conceiving of situations or issues in terms of relevant whole

systems, with a consequent effort of

"sweeping

in" a broad range of circumstances and considerations

(Singer, 1957; Churchman, 1968, 1982) – can help us avoid

such selectivity and partiality and thus can secure a higher

degree of rationality than conventional analytical thinking

can. In practice though, the quest for comprehensiveness is

bound to fail inasmuch as it finds

no natural limit. It is a

meaningful effort but not an arguable claim. Accordingly,

the sweep-in principle cannot resolve or avoid the problem of

the inevitable selectivity and partiality of all practical claims

to relevant knowledge, rational action, and resulting improvement.

Rationality and selectivity are inseparable siblings, regardless

of whether we take a systems approach or not. This is why in

my work on critical systems heuristics (CSH),1)

the principle

of boundary critique – the requirement of promoting

a reflecting and transparent employment of the boundary judgments

that are constitutive of our reference systems – had ultimately

to

replace Singer and Churchman's sweep-in principle as a methodological

core principle of systemic thought and practice (Ulrich,

2004, p. 1128).

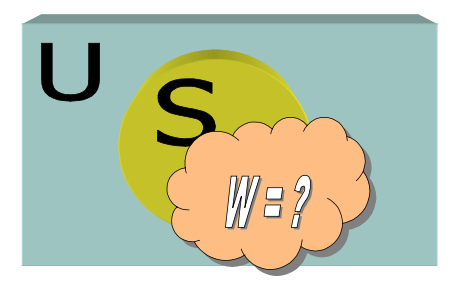

Rationality

and

reference systems Critical systems thinking begins

when we first realize that our reference systems of thought

and action (S) do not usually comprise all the aspects

of the universe (U) that might conceivably be relevant and on

which our claims may consequently depend (Fig. 1).

Fig.

1: Reference system vs.

universe

U

= universe; S = current reference system of thought and action.

Critical systems thinking begins when we realize that our reference

systems (S) for judging situations and for assessing related

claims may (and as a rule, do) not comprise all the aspects

(or conditions, circumstances) of the universe (U) that would

allow conclusive arguments to systemic rationality.

We

may refer to the unknown section of the universe that in a specific

situation or issue would allow conclusive arguments to sufficient

knowledge, rational action, and resulting improvement as the

"relevant whole system" (W).

The difficulty is, we do not and cannot usually know W, for it represents

a totality of conceivably relevant conditions or of related

circumstances, concerns, and ideas and as such lies beyond

the reach of empirical knowledge or, in any case, beyond what

from a critical point of view we should assume to know for sure.

There is, in this sense, a critical difference between

S and W (Fig. 2).

Fig.

2: The "critical difference"

in systems thinking

The

proper reference system for arguing claims is not a matter of

course but rather, a matter of discourse! U = universe; S = current

reference system of thought and action; W = the "whole relevant system"=

the totality of

circumstances and concerns that in principle would allow for

conclusive argumentation of related claims to knowledge, rationality,

or improvement, but which in practice we can hardly ever claim to fully

and securely know.

We

are facing an eternal dilemma of reason: the

quest for considering everything possibly relevant is as unachievable

in practice as it is indispensable in theory. Assuming that

we can live up to it and indeed consider everything relevant

leads to dogmatism (e.g., in the form of boundary judgments

taken for granted); abandoning it, to uncontrolled deficits

of rationality (e.g., in the form of neglected "external

effects" and suboptimization). Responding to the dilemma

by discarding the systems idea does not help either, for that

would merely mean to accuse the messenger of causing the bad

news it brings us. But the systems idea is neither the cause

nor the solution of the problem, it is only the messenger. The

only reasonable way out is to take the messenger seriously and

choose the critical path, that is, undertake a systematic

effort of dealing carefully and openly with the deficits

of knowledge and rationality in question. While we cannot avoid

such deficits, we can at least deal carefully with them and

make an effort to lay them open to all those concerned. We can

trace their sources in the assumptions of fact and value that

guide us. We can analyze their actual or potential consequences,

that is, the ways they may affect people. And we can then assess

the claims in question in the light of these assumptions and

consequences and can qualify (i.e., specify and limit) their

meaning and validity accordingly. That is what critical systems

thinking and its central methodological principle of boundary

critique are all about.

The

critical path or how to handle reference systems Given

the importance of reference systems for our constructions of

rationality, a critical path will have to dedicate special attention

to their choice and handling. In particular, it will not allow

the systems perspective, with its focus on a system or situation

of interest (S), to become the only reference system for claims

to knowledge and rationality. Accordingly, from a critical systems

point of view, our handling of (S) should never assume that:

- S

= the only reference system that matters for adequate and

rational practice;

- S

= W, that is, the system or situation of interest exhausts

the totality of relevant conditions, circumstances,

and concerns (a basic error of thought to which

virtually all conventional systems thinking submits);

- W

= S + E, that is, the system of concern (S) and its

environment (E) exhaust the "relevant whole system"

(W) or even the total conceivable universe of discourse

(U); and that

- we

ever have sufficient knowledge of W or even U to fully

justify our claims regarding S and E.

Critical

systems thinking (CST) is to avoid these common pitfalls

of conventional systems thinking. They all are rooted in

a mistaken identification of S with W, that is, in a tendency to elevate S to the only reference system considered

for judging rationality. This is why CST is essentially

about what above we have called the "critical difference"

between S and W:

CST

= f (Δ{W-S})

To

be sure, the notion of a whole relevant system (W) is a vague

and problematic one. I use it rarely and for critical purposes

only, that is, as a conceptual tool that reminds us of the

inevitable imitations of any reference systems S on which we

may choose to rely. The essential methodological consequence

of this reminder is that we need to resist the temptation of

making the system of primary interest or concern an unquestioned reference

system for assessing claims. To put it perhaps a bit more succinctly,

a basic imperative of critical systems thinking is this:

Never

try to solve "the problem" of the system

without

also making "the system" the problem.

Thus

understood, critical systems thinking always faces us with the

question of whether the situation or context considered

provides the proper reference system for identifying relevant

"facts" and "values" and for accordingly

justifying claims to relevant knowledge, rational action, and

genuine improvement. Consequently we should always ask:

What

"critical difference" might a shift of perspective

make,

from the assumed system of concern (S) to different

notions

of the whole relevant system (W)?

It

is with a view to making this question a focus of systematic

methodological attention – in short, to "making the

system the problem" – that in my work on critical systems

heuristics (CSH), I have found it useful to rely on a standardized

basic typology of reference systems (Ulrich, e.g., 1998 and

2017d). We may then understand such a typology as a basic conceptualization

of the "critical difference" between S and W.

A typology of reference systems

for boundary critique To guide systematic

reflection on the conditioned nature and limited reach of our

claims – to practice boundary critique, that is – CSH

relies on these four ideal-typical

rationality perspectives:

S

– the situation of concern or system of primary interest;

E

– the relevant environment or decision-environment;

A

– the context of application or of responsible

action; and

U

– the total conceivable universe of discourse or

of potentially relevant circumstances (see Ulrich, 2017d, pp.

17-28).

CSH

takes these four types of reference systems to embody four fundamentally

different rationality perspectives, each of which is essential

for a systematic practice of boundary critique and is accordingly

also informing some of the boundary questions that together

make of the standard checklist of boundary questions used in

CSH.2) (The French

word seau – whence comes the acronym S-E-A-U – means as much as bucket, pot, or

pail and is thus apt to remind us of the idea that all four

perspectives belong to the toolbox of boundary critique.) In

what follows, I would like first to briefly explain why the

four reference systems are actually needed (i.e., what is the

underlying logic) and

then to take a closer look at the rationality perspectives they

embody (i.e., how does this logic translate into rational practice).

Two related

core concepts will be what I call "the missing element"

in the conventional logic of systems thinking and a resulting

"three-level concept of rational practice" for critical systems thinking and practice.

"The

Missing Element" The way I introduced

the four types of reference systems in Part 1 of the previous

essay (Ulrich, 2017b) was in terms of the kind of boundary judgments that

shape our mental constructions of "the system" and

which consequently allow us to trace the selectivity of related

claims. A slightly different way is to

look at the criteria for what "matters" in a situation

and how what matters is related to S. Four such relations are logically

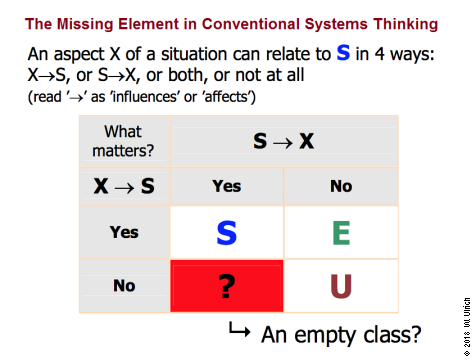

possible (Fig. 3).

Fig.

3: The "missing element"

in systems thinking

Conventional

systems thinking is based on the systems / environment distinction.

By assuming that the universe of discourse is exhausted by the

reference systems S and E, such thinking leaves open the question

of the nature and relevance of the "missing element"

located in the red box, apart from tacitly narrowing the meaning

of "relevance" to what matters to S.

U

= universe; S = system of primary interest or concern; E = relevant

environment (relevant, that is, to S); ? = "missing element"

= gap in the argumentation logic of conventional systems thinking

Of

these four relationships, three (S-E-U) can easily be understood

in terms of the conventional reference systems of systems thinking,

that is, the system of primary interest or concern (S), the

relevant environment (E), and the remaining universe (U, also

called the "irrelevant environment"). The boundary

judgments that this conventional logic of systems thinking requires

are (a) the delimitation of S from E (S/E) and (b) the

delimitation of the environment considered relevant from

that considered irrelevant (E/U). But what about the fourth

relationship, the one marked by the red box in Fig. 3?

In conventional systems thinking, this fourth basic relationship

appears to be an empty class, as no corresponding reference

system is identified and dealt with systematically, that is,

as a constituent of any claim to systemic rationality. There

is a gap here in the argumentation logic of conventional systems

thinking that I have hardly ever found to be recognized and

systematically questioned.

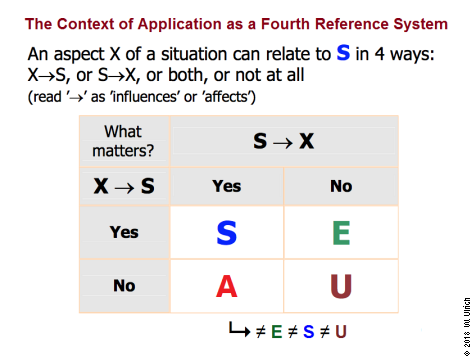

The

"context of application" This fourth

relationship is what in CSH is called the "context of application"

or also the "context of responsible action" or of

accountability. It is a mandatory

part of the suggested S-E-A-U formula of boundary critique (Fig. 4);

but as far as conventional systems thinking is concerned, it

has remained a "missing element" in its table

of reference systems.

Fig.

4: The "context of

application" in critical systems thinking

In

conventional systems thinking, situational aspects or conditions

that influence the system of primary interest but which cannot be

controlled by it are considered "environment" in the

sense that they constitute the system's relevant decision-environment

(E). As they condition the outcome of systemic rationality or,

in everyday terms, the system's success, there is an intrinsic

interest to take the thus-understood environment

into account. This is different from the context of application

(A), which comprises all those situational aspects that are

affected by (claims to) systemic rationality or, in everyday

terms, by the system, but have no influence on it (i.e., the

way rationality is defined and measured). A, then, is not part

of the relevant environment E of S but rather, S is environment

for A. Accordingly the implications of systemic rationality

for interests and concerns treated as A are often neglected

or considered as "external effects" about which one

cannot do much, rather than as a systematic part of all claims

to rationality.

The

designation of A as "context of application" comes

from science-theory, which conventionally distinguishes between

three methodologically different tasks of research, concerning

its proper handling of the contexts of discovery, of justification,

and of application of scientific propositions. The aim is to

narrow the relevant context for validating propositions so that

the circumstances of their emergence as well as the practical

applications to which they lend themselves may be considered

irrelevant for their justification. In distinction to this conventional

view, the point of introducing A as a reference system for judging

claims is of course that in the applied disciplines, and indeed

in all inquiry that may eventually be put to practical use (that

is, in virtually all forms of inquiry), considering the context

of application is essential for justifying claims. In

fact, it makes sense to conceive of the justification of all

practical claims – to relevant knowledge, rational practice,

and resulting improvement – in terms of the context of application,

regardless of whether their context of discovery is science

or everyday experience, for the selectivity of the claims in

question remains the same. Well-understood science distinguishes

itself from other forms of research and practice not by being

free of selectivity but rather, by laying it open. We can then define the context of application

quite generally as the real-world context in which a claim's

consequences, when used as a basis for action, become manifest

and should be systematically examined and justified.

There

have been a number of efforts in recent decades to do more justice

to the context of application (see, e.g., Beck, 1992, 1995;

Gibbons et al., 1994; and Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993, 1995);

but neither the prevalent science-theory nor the dominating

research practice appear to have taken much notice of them.

Originating in the Vienna Circle's tradition of logical empiricism

(e.g., Carnap, 1937; Ayer, 1936; Reichenbach, 1938) and in Popper's

(1959, 1963, 1972) subsequent work on critical rationalism, the prevalent model of science

today has remained focused on the "context of justification"

as distinguished from the "context of discovery,"

a distinction first introduced by Reichenbach (1938, pp. 6f,

382) and later particularly emphasized by Popper. Even less importance is given in this model to

the "context of application," the real-world situations

in which scientific knowledge becomes "applied science"

and in which accordingly it is supposed to secure successful and

rationally defensible practice, that is, ultimately,

some kind of improvement of the human condition. In any case,

what I wrote about the issue

some thirty years ago still remains a continuing challenge:

Epistemologists

such as Karl. R. Popper (1959, 1963, 1972) have claimed that

the context in which science is applied is relatively irrelevant

for the justification of its propositions. In distinction to

this position, I propose to understand – and indeed define –

applied science as the study of contexts of application. Of

course this definition renders the distinction between the two

contexts obsolete. From an applied-science point of view, the distinction

is really quite inadequate: to justify the propositions

of applied science can only mean to justify its effects upon

the context of application under study. (Ulrich, 1987, p. 276)

In

an age in which virtually all science sooner or later tends

to become applied science and in which, conversely, ever more

realms of practice are influenced by scientific research and

professional expertise, the distinction between the context

of justification and the context of application has indeed become

obsolete. This is the more so if one considers how frequently research-based

practice produces adverse external effects, cases of obvious

suboptimization, and

situations of "organized irresponsibility" (Beck,

1992, 1995). The implication can only be that the context of application

is rapidly becoming an indispensable part of the context of

justification. Yet in conventional

systems thinking, as in many other fields and methodologies

of inquiry, the context of application is still not systematically

considered.

Environment vs. context of application There is a frequent

confusion in that calls for considering the "environment"

are mistaken to ensure a concern for the context of application.

However, in systems thinking and in the many fields that have

been influenced by it, the relevant "environment"

is usually understood in a different way. The focus is on a

system's decision-environment, that is, the situational

aspects or conditions that influence the system of primary interest

but cannot be controlled by it. As they co-produce the system's

success or, in the terms of CSH, condition the outcome of systemic

rationality, there is an intrinsic interest on the

part of those involved to take the thus-understood

environment into account. Accordingly it is also called the "relevant environment,"

meaning that part of the environment which has repercussions

on the system. In this sense, then, systems management

– the pursuit of systems rationality – includes environmental

management, though not necessarily a stance of ecological concern.

We are dealing with a managerial understanding of the environment

that has little to do with what the concept of the application

context intends; in fact it runs counter to it.

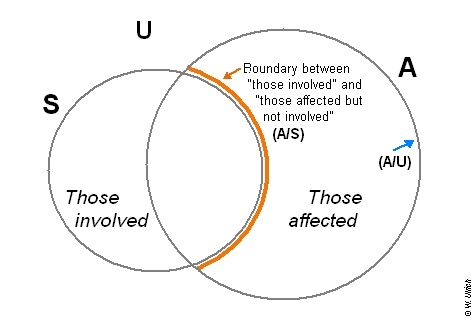

Those

involved vs. those affected In

distinction to the relevant environment (E), the context of application

(A) comprises all those situational aspects that are affected

by "the system" or related claims to systemic rationality

but which are not included in the reference system for assessing

systems rationality or success. In consequence, the context

of application tends to be

taken into account – in short, to "count" – systematically only inasmuch as it happens to coincide

with S or E, which is the case to the extent the affected parties have

ways to influence the way "systems rationality" is defined

or to coproduce a corresponding measure of "success."

For the rest, S is relevant environment for A rather

than the other way round. The methodologically essential focus

will therefore be on those situational aspects – concerned

parties or interests – that are treated as A only. The crucial boundary issue concerns

the delimitation of those affected but not involved from

those affected who are also involved (A/S). A graph offered

in two previous publications may make this clearer than many

words, I reproduce it here for the reader's convenience (Fig. 5).

References to "those affected"or simply to "A," unless otherwise

specified, will accordingly

be understood to focus on the group of those affected

but not involved.

Fig.

5: Those involved vs. those affected but not involved,

and

how they relate to the two reference systems (S) and (A)

S = system (or

situation) of primary interest, A = context of

application, U = universe. While

A as delimited from U (A/U) includes all those

affected and thus provides the basic reference system for responsible

action, the crucial boundary issue is often how those affected

but not involved (A/S) are treated. (Source: adapted from

Ulrich, 1983, p. 248, and reproduced from Ulrich, 2017d,

p. 23, cf. pp. 19-27 for definition and discussion of reference systems E,

A, and U.)

The

context of application vs. the universe Remains

the fourth reference system, the universe (U). Apart from being

a logically needed residual category, it takes on a specific

methodological meaning when it comes to dealing critically with

the normative3)

content of systems rationality:

it refers us to the Kantian principle of moral universalization,

better known as Kant's (1786) "categorical imperative."

The idea is to question the way we delimit the context of application

– the external effects and concerns to be considered – as distinguished

from the universe of all other, actual or conceivable, known

or unknown external effects, many of which may be beyond closer

consideration. Kant's idea was that a subjective norm (or maxim,

as he says) of action cannot count as morally arguable and in

this sense rational unless all those affected could in principle

agree. The difficulty is, how do we know whether they could?

Kant invented the categorical imperative as a practical

universalization test: it asks us to put ourselves in

the place of all those effectively or conceivably concerned

and check whether we could then still find the maxim in question

to be arguable, and thus generalizable (i.e., a general norm

of action rather than just a subjective maxim). In our epoch,

Apel (1972) and Habermas (1990) have uncovered the communicative

kernel of the categorical imperative and hence have translated

it into a model of rational practical discourse, an idea

that is beyond adequate discussion in this Postscript but which

I have discussed extensively on a number of other occasions

(see Ulrich, 2009a-c; 2010a, b; 2011b; 2013; 2015). Suffice

it here to note that (U) is a relevant reference system inasmuch

as in morally arguable practice, the delimitation of A against

U is to be considered no less carefully than all other boundary

issues (S/E, E/U, and A/S).

The

"three-level concept of rational

practice" In his ground-breaking

work on "ideal-types" of rational action,4)

the German sociologist Max Weber (e.g., 1968, pp. 6-9, 20f)

distinguished between social and nonsocial action on the one

hand and between rational and nonrational action on the other.

Action is "social" when it is oriented towards mutual

understanding in the double sense of sharing individual ideas

about what is good and rational action with others and trying

to find agreement on them; it is "nonsocial" when

it is oriented towards securing one's owns interest or success

by means of purposive-rational action. Further, action is "rational"

rather than "nonrational" to the extent it is guided

consciously and coherently by either of these two orientations,

with the added benefit that an objective interpretive can better

recognize it as such. From these distinctions Weber derived

four (in practice: more or less) coherent types of action,

the intrinsic logic of which an observer can rationally

understand (in the order of decreasing weight of rational as

compared to empathetic understanding):

–

purpose-rational action uses efficacious means

for reaching ends;

– value-rational action

is consistent with underlying values;

– affectual

action responds to empathetic or emotional reasons;

and

– traditional action follows individual

habit and social custom

(cf.

Weber, 1968, esp. p. 24f).

Weber's

account is complex and need not concern us here in any more

detail, the more as interested readers will find my understanding

of it explained elsewhere (Ulrich, 2012b, pp. 4-18). For our

present purpose it will be quite sufficient to rely on a helpful

revision of Weber's typology by Jurgen Habermas (1984, pp. 284-288),

a revision that was motivated by the attempt to incorporate

the "communicative" side of rational action, along

with a shift of perspective from that of an understanding observer

(aim: "interpretive social science") to that

of a responsible agent (aim: "theory of communicative

action").

Like

Weber, Habermas starts by distinguishing situations of social

from nonsocial action. But he then adds a distinction that matters

for identifying the quality of social action, between "consensus-oriented"

(or communicative) and "success-oriented" (or noncommunicative)

orientation, rather than just distinguishing with Weber between

rational and not so rational orientation (the latter distinction

is implicit in the proper use of ideal-types). It helps to understand

the intent of the additional distinction by recalling Habermas'

(1971) earlier, largely parallel distinction between "work"

and "interaction" as two fundamental dimensions of

practice that go back to Aristotle's concepts of poiesis

(work, production) and praxis (action, interaction).

Cross-tabulating the two distinctions yields three basic types

of rational action, one standing for a "nonsocial"

type of rationality and the others for two variants of the "social"

type (Table 1).

|

Table 1: Social

and nonsocial types of rational action

(Source: adapted

from Habermas 1984, p. 285, cf. Ulrich, 2012b,

p. 26 )

|

|

Action

situation

|

Action

orientation

|

|

Noncommunicative:

"Success"

(own

interest)

|

Communicative:

"Consensus"

(mutual

understanding)

|

|

Nonsocial

|

Instrumental

action

|

—

— —

|

|

Social

|

Strategic

action

|

Communicative

action

|

|

Copyleft  2012 W. Ulrich

2012 W. Ulrich

|

"Instrumental"

action represents a type of nonsocial action that is

oriented toward what Weber called purpose-rationality, a rationality

that is defined by the choice of efficacious means for achieving

given ends. As Habermas puts it, it pursues a type of rationality

that in its pure form is not oriented towards securing mutual

understanding as a value of its own but only towards securing

"success" in the limited sense of reaching the end

as fully and efficiently as possible. By definition, then, there

is no "communicative" variant of nonsocial action

and for this reason, the corresponding box in the table remains

an empty class. Such a type of rationality, if it existed, would

violate Weber's requirement of a recognizable internal "logic"

or coherence; in the terms of Habermas, an agent cannot adopt

a nonsocial orientation (i.e., prioritize a private utilitarian

rather than a communicative and cooperative agenda) yet claim

to be oriented towards mutual understanding or "consensus"

rather than "success."

"Strategic"

and "communicative" action, by contrast, both represent

types of social action. Since such action may be oriented

towards either success or consensus, there are two ideal-types

of socially rational action. When oriented primarily to success,

social action is interested in the concerns of others only in

the opportunistic sense of securing its own success by taking

into account their intentions and actions; it represents a "strategic"

type of rationality rather than a "communicative"

orientation in the full sense of securing mutual understanding

and cooperation. This latter orientation is what "communicative

rationality" as Habermas understands it is about; the ideal-typical

focus is on reaching "consensus" rather than "success"

or, to put it differently, its notion of success is oriented

towards a type of rational action that is coordinated discursively,

by "communicative practice" rather than merely strategic

behavior (cf. Habermas, 1984, p. 101).

The

merit of Habermas' reading of Weber's typology of rational action

is that it lends itself to much further reaching critical use.

This is so because it overcomes several of the difficulties

in Weber's attempt to clarify the meaning of rational action

within his framework of interpretive social science, I mean

particularly its identification of purpose-rationality with

the most rational type of action and its lacking grasp of the

social (meaning both intersubjective and societal) dimension

of well-understood "rational" practice. As I would

argue, Weber's inadequate grasp of what rational social

practice means is rooted precisely in his focus on interpretive

social science: it caused him to mistake the internal

"logic" or coherence of individual action for a major

criterion of socially rational action. Such a perspective is

meaningful for an interpretive

observer, but not for a responsible agent. Weber ended up elevating

purpose-rationality to the highest level of his typology of

rational action simply because it is the type of rational action

that is most easily recognized – or as Weber might put it, the

internal logic of which is most easily interpreted – by an objective

observer. The result is a fundamental confusion between the

rationality of the social scientist's understanding on the one

hand and that of the social practice to be understood on the

other hand. As the former moves into focus, the latter becomes

blurred and ultimately vanishes from sight (see Ulrich, 2012b,

p. 19f).

Integrating

the communicative dimension of rational action, among other

important merits such as its opening up the perspective of a

discursive concept of rationality, has the advantage of overcoming

Weber's fixation on purpose-rationality and thereby opening

up new horizons for rational critique and improvement of social

practice. As Habermas puts it:

The

theory of communicative action can make good the weaknesses

we found in Weber's action theory, inasmuch as it does not remain

fixated on purposive rationality as the only aspect under which

action can be criticized and improved. (Habermas, 1984, p. 332)

Three

types of rationality critique Let us see,

then, how this basic typology of rational action might be put

to critical use within a framework of critical systems thinking

and practice. To this end we need to clarify the relations between the three ideal-types

of rationality – instrumental, strategic, and communicative

–

a bit more. How precisely should we understand and handle their

basically complementary, yet in practice often conflicting,

nature? Is there a way to use them

so that together they can ensure rational practice? And

hence, do they lend themselves to constructing a practicable,

integrated model of rational practice?

I

propose that a satisfactory answer depends on a transition from

Kant's (1786,

1787) two-dimensional concept of reason (theoretical vs. practical

reason), which we still recognize in the framework of Habermas

(success vs. consensus, work vs. interaction, noncommunicative

vs. communicative rationality), to an integrated, hierarchical

concept. A multi-level conception of

rational practice converts the merely "horizontal"

addition of practical reason to theoretical-instrumental

reason into a vertically integrated conception,

so that practical reason is construed as a higher

(or perhaps better, richer) level of rationality that incorporates all lower levels.

I have long since used such a framework in my work on critical

systems thinking (see esp. Ulrich, 1988, pp. 146-160; 2001b, pp. 79-82; and 2012b,

pp. 31-34); but its focus was on integrating the normative

dimension of systems rationality into contemporary,

science-based and often also one-sidedly technical and/or

managerial notions of rationality, rather than on operationalizing

boundary critique. In short, the aim was to explain the nature

of rational practice, while now it is to explain the reference

systems for boundary critique. Here, then, is the latest version of my three-level concept

of rational practice (Table 2).

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

PDF file

Note: This

s a postscript to the preceding two-part

essay on "Systems thinking as if people mattered"

(Ulrich, 2017d, e). It takes up the notion of reference systems

for boundary critique and aims to cast a little more light on

the different rationalities they embody, by situating them

in the author's earlier three-level concept of rational practice

(Ulrich, 1988, 2001b, and 2012b).

|

|

|

|

This

new version of the model now explicitly ties the quest for rational practice to

systematic boundary critique, which thus becomes an integral

requirement of all applied rationality critique. To each of its three levels of systems rationality,

the model assigns a

conforming type of reference systems, as defined in the S-E-A-U

formula of boundary critique. Conversely, the scheme can be

understood to work out the different rationality perspectives

for which the reference systems stand. The explanation thus

works in both ways: rationality perspectives can be explained

in terms of boundary critique, and boundary critique in terms

of rationality perspectives.

A

further,

essential element of a proper understanding and employment of

the model consists in what I propose to call the principle of critically

vertical integration of systems levels. Since introducing

it requires a bit more space, I will do so in a separate, concluding

subsection below. First, I suggest we very briefly consider

some of the main theoretical merits of a multi-level conception

of rational

practice and then illustrate its practical implications – the

difference it can make for our understanding of rational practice –

by means of two examples.

Regarding

the more theoretical merits, there are some rather

obvious advantages of the shift from a horizontal to a vertical

understanding of systems rationalization. Conventional

horizontal conceptions of systems rationality

locate gains of rationality primarily in an expansion of systems boundaries;

they have therefore tended to overlook the need for not only enlarging

but also questioning and changing the reference systems presupposed

in claims to rationality. At the same time, they have found

it difficult (and have usually failed) to integrate the normative/communicative dimension

of rationality, that is, to give it a systematic place

in the quest for rational practice and in conforming efforts

of rationality critique. A multi-level framework can help to reduce these difficulties

along the following lines (I'll content myself with simply

listing them, without

discussing them any further):

(1)

Most basically, the framework puts the three ideal-types of

rational action (as summed up in Table 1 and emerging from

the sociological tradition of Weber and Habermas) into a compelling

yet simple order and thereby clarifies their meaning and

mutual relationship.

(2)

It connects the three Weberian

/ Habermasian ideal-types of rational action with the

two traditions of practical philosophy and of systems

theory, and thereby corrects a fundamental

deficit of Weber's typology of rational action, it's not being

grounded in practical philosophy, along with the missing recognition

of the role of boundary critique in Habermas' work.

(3)

It gives new meaning and practical significance to Kant's two-dimensional conception of reason and thereby

to his demand for the primacy of practical reason, thus helping

us to breathe new life into practical philosophy and to pragmatize these two basic ideas

of it.

(4)

It enriches the "horizontal" thrust of conventional

systems thinking, towards expanding systems boundaries, by a

methodologically more fruitful "vertical" perspective

of conceptual levels of progressive rationalization of systems

(compare on this Feibleman's notion of "integrative

levels" as discussed in the concluding section on "vertical

integration").

(5)

It integrates the communicative turn of our understanding of

rationality, as introduced by Karl-Otto Apel (e.g., 1972) and

Jurgen Habermas (e.g., 1984), into the practice of rationality

critique and thereby paves the way for a critically-normative

and discursive concept of rationality, another missing element

in the prevalent, scientifically oriented conception of reason.

(6)

Last but not least, it systematically relates the three ideal-types

of rationality to the reference systems for boundary critique

proposed by the S-E-A-U scheme of CSH and thereby is apt to

deepen our understanding of both, the idea of a three-level

concept of rational practice and the meaning of the related

reference

systems for boundary critique.5)

It is

obviously the last of these six points that interests us here particularly.

Understanding Weber's

and Habermas' ideal-types of rational action in the terms of

corresponding reference systems for boundary critique is to my

knowledge a new idea. More importantly, I see in it the key

for developing a conception of critically-normative practice

that unlike Habermas' (1979, 1990, 1993) ideal conception of

discursive rationality, which ties rational consensus to ideal

conditions of practical discourse, is both theoretically convincing

and practically achievable. This is so because boundary critique

allows critical argumentation on all aspects and implications

of claims to rationality, including its normative implications,

without depending on conditions of perfect rationality. Quite

the contrary, as it does not depend on any particular knowledge

or skills that ordinary citizens would not be able to have,

boundary critique is apt to promote a new kind of symmetry

of critical competence among experts, decision-makers, and

citizens so that they can all meet as equals (see Ulrich, 1993

and 2000).

At

the same time, I should emphasize that the six listed points are interdependent.

Together, they open up a systematic perspective

for bringing back in to our contemporary conception of rationality

the practical-normative dimension that has largely been lost

with the rise of science and the expansion

of theoretical-instrumental rationality it brought. At good

last, we may hope to find some systematic ways for "disciplining"

the dominance of instrumental rationality, and thus to recover

some of the lost balance between theoretical and practical reason:

Both

philosophically and pragmatically speaking, … the quest for

rational action needs to break through the usual dominance of

theoretical-instrumental rationality. To this end, we need to

"discipline" the use of theoretical-instrumental rationality

by subjecting it to the primacy of practical reason, thus advancing

from a state of mere co-existence of theoretical and practical

reason ("mere" in that it remains methodologically

undefined and gives us no orientation as to how to handle their

clash) to an understanding of rational practice that gives practical

reason a chance. (Ulrich, 2012b, p. 32)

Such

an understanding of rational practice should

make it definitely clear that the three

underlying ideal-types of rational action do not embody meaningful

alternatives, not any more than Kant's two dimensions of reason

do. Rather, they are part and parcel of an integrated concept

of levels of systems rationalization, whereby each level is

characterized by a specific type

of reference system for rationality critique (which in turn

is supported boundary critique). Although in

actual practice the three levels may of course be developed

to varying degrees, it is clear that good practice depends on

giving due consideration to all three levels, as each depends for its

full rationalization on the other two. Any

gains of rationality at the two higher levels must build on

the two lower levels, and at the same time, the upper levels must

provide

orientation to the good use of the lower levels. The scheme

thus suggests that the handling of each level is deficient so

long as it is not informed and supported by the other two. Consequently,

the three rationality perspectives

each also lend themselves to critical use with respect to the other

two, in addition to their relevance for examining claims at

their own level of systems rationalization. Accordingly, the

three-level concept of rational practice can also usefully be

understood as a framework for applied rationality critique.

To

illustrate the practical relevance of the three levels of critique

and the ways they are tied to the reference systems

S, E and A, I have added in the right-hand column of Table 2

an example of their interpretation in the field of corporate

management.6)

In management terms we can understand the

three rationality perspectives of S, E, and A to focus on these

three management levels (beginning with the lowest level):

–

operational systems management, in which the focus is

on the management of cost and resources (i.e., building up potentials

of operational success, with the main system of concern being

S);

–

strategic systems management, in which the focus is on

the management of complexity (i.e., developing steering capacities

in view of uncertainy and change, with the main system of concern

being E); and

–

normative systems management, in which the focus is on

the management of conflict (i.e., building up potentials of

mutual understanding with all the parties concerned).

In

short, the three rationality perspectives can be characterized

to focus on managerial core issues related to the management of cost, of complexity, and of conflict.

To be sure, this is not an entirely new idea. Such multi-level frameworks have been proposed

before, for example by

Jantsch (1970, 1975), Beer (1972

/ 1981), Espejo et al. (1996),

and Schwaninger (2001, 2009). However, while these schemes offer a useful extension

of the management and planning approaches of the fields in which they were developed, among them technological

forecasting and planning, organizational cybernetics, and management theory,

they differ from the scheme suggested here in one important

respect: they are not grounded in practical philosophy.

In the terms of Habermas' typology (Table 1), they remain more

or less

limited to an orientation towards success (with the "less"

applying to Jantsch's framewok, to which we will return below).

Accordingly their

highest level of systems rationalization remains that of strategic

management. They have no means for dealing with the communicative

requirements of conflict management that arise when it comes

to resolving normative issues, including ethical and moral

issues, by means of openly and critically normative argumentation

and discourse. In contrast, the three-level concept of rational

practice suggested here is grounded in practical philosophy

and for this reason can overcome the other schemes' tacit limitation

to a merely managerial and strategic notion of rationality that

remains tied to an orientation to success. The aim of the present

framework reaches further, at what on an earlier occasion I described as vindication beyond mere reference to self-interest, that

is, as an understanding of rationality that includes reference

to the views and values of parties other than those directly

interested and involved – the very core idea of "communicative

rationality" (see Ulrich, 2011a, p. 9f).

These few remarks must suffice here; for a detailed discussion

of the three management levels as understood in the management

literature and in my work on critical systems thinking, I may refer

the reader to the earlier-mentioned essays (Ulrich, 1988, 2001b,

and 2012b).

Two

application examples

To help readers in appreciating the

relevance

of the proposed three-level framework of rational practice,

let us now turn to two major examples of application. I adapt

them here from earlier discussions (see Ulrich, esp. 1988 and 2012b).

First

example: "Stakeholder

management" In the seminal

text on "stakeholder theory," Freeman (1984, p. 46)

defined stakeholders as "any group or individual who can

affect or is affected by the achievement of an organization's

objectives." A similar, slightly shorter definition defines

them as "groups or individuals

who can affect, or are affected by, the organization's mission"

(p. 52). The definition is widely cited and accepted to this day,

yet it is so underspecified that it is hardly useful, in fact,

it glosses over the problems it raises. There is no mentioning

of the boundary judgments involved, and accordingly no specification

of criteria and processes for the boundary critique that would

seem required for critical practice (cf. Achterkamp and

Vos, 2007). Even worse, the definition glosses over the crucial distinction between stakeholders who

are in a position to influence the organization's success or

mission and thus the ways it affects them, and others who

cannot. In the terms of our earlier Fig. 5, doing justice

to stakeholders requires a clear distinction between those involved

and those affected but not involved.

From

a perspective informed by our three-level model of rational

practice, it is indeed crucial to carefully distinguish the

two groups, as they belong to different reference systems. The

first group, inasmuch as it is not identical with those involved

in the organization (reference system: S) belongs to the organization's

decision-environment (reference system: E), which is that

section

of the universe which affects the system but is not part of

it. The second group, in contrast, comprises all those stakeholders

that are or risk being affected without having any influence

upon the organization; they are, in the terms of CSH, the group

of "those affected but not involved" (reference

system: A).

As

soon as one understands the two stakeholder groups in such terms

of boundary critique and related reference systems, it becomes

clear that glossing over their different nature in the way Freeman's

definition does it is bound to lead into an inadequate treatment

of the second group. Its treatment risks being perceived to

be of secondary importance as no repercussions are expected

for S; it is to S part of the "irrelevant" environment

(U) rather than of the "relevant" environment (E).

Not surprisingly, then, stakeholder management has achieved

little in strengthening corporate social responsibility for

all stakeholders, not just for those who are in a position to affect

the corporation's success and whose correct treatment is therefore

in the very interest of corporate management. This is indeed what has happened,

and continues to happen regularly, in the

practice of this so-called "stakeholder theory."

In the

terms of the three-level concept of rational practice, stakeholder theory has remained limited to the

strategic level of systems rationalization. It has no conception

of the normative level and its need for boundary critique oriented

towards careful identification and handling of the context of application

(or of responsible action). This limitation comes as no surprise,

given that stakeholder theory was developed

within the horizon of the strategic management literature. As

a representative text book of strategic management (Thompson

(1997) puts it bluntly, a key concern in taking account of the

needs of different parties concerned by the corporation's aims

and activities is indeed a party's power to affect the corporation's

success:

Stakeholder

theory postulates that the objectives of an organization will

take account of the various needs of these different interested

parties who will represent some type of informal coalition.

Their relative power will be a key variable, and the organization

will on occasions "trade-off" one against the other,

establishing a hierarchy of relative importance. (Thompson,

1997, p. 148)

Mind

you, the stakeholders will be ranked regarding their importance

according to their "relative power" to affect

the organization or its success, not the other way round, according

to the severity of the ways in which they may be affected. In

the terms of Figures 3 and 4 above, what is taken to "matter"

for the organization's response to stakeholder concerns – the

way it will treat these concerns – is the relation X–>S rather

than S–>X; which is to say, the reference system identifying

relevant concerns and rational responses is taken to be E, not

A. In everyday terms: thus-understood stakeholder management

is motivated by the organization's own interests rather than

by the genuine interests and concerns of third parties, particularly

if they have little power. One must wonder, then, what should

be new in stakeholder theory as compared to previous management

theories in its handling of third parties. After all, the reference

systems for assessing managerial or organizational "success"

and related rationality claims remain the same (S/E).

The level

of communicative rationality and its normative core thus remain

outside the conceptual grasp of stakeholder theory. With its

deficient definition of stakeholders, it misses its aim from

the start. The underlying concept of rational practice remains tied to the

idea of building operational and strategic potentials of success, rather than

opening up the universe of discourse to ethical and moral

issues of dealing with genuine conflicts of interests and needs,

of views and values, whereby all the parties concerned would

be treated with equal regard for their concerns, regardless

of the influence they have upon the

organization. The conclusion is inevitable: due to its being

grounded

in strategic management but not also in practical philosophy, stakeholder theory

fails to do justice to the level of normative management and its requirements

of critically-normative discourse. This theoretical deficit

need not

of course preclude that individual managers of good will may still

want to do justice to the concerns of all affected parties;

but such a personal stance will not be a systematic part of the

systems rationality at work. It does not "count"

in the system's measure of success and worse, to the extent

that caring about the interests of third parties may involve

some cost, such managers of good will even risk being accused

of not living up to their full responsibility for the organization's

success.

Stakeholder management

has thus become for managers a lip service paid routinely – a

managerial ritual, so to speak – rather than a new stance of responsibility,

much less a new concept of corporate rationality. As Freeman himself avows in explaining

his above-cited, crucial definition of stakeholders,

the outlook remains basically utilitarian or oriented to "success"

rather than to mutual understanding and cooperation with all

the parties concerned:

From

the standpoint of strategic management, or the achievement of

organizational purpose, we need an inclusive definition. We

must not leave out any group or individual who can affect or

is affected by organizational purpose, because that group

may prevent our accomplishments. Theoretically, therefore,

"stakeholder" must be able to capture a broad range

of groups and individuals, even though when we put the concept

to practical tests we must be willing to ignore certain groups

who will have little or no impact on the corporation at

this point of time. (Freeman, 1984, p. 52f, italics added;

compare also Freeman's additional reference to the "stakeholders whose support is necessary for survival"

on p. 33.)

From

the outset, stakeholder management thus fails to recognize –

or take seriously – the

conflict of rationalities involved. It knows only one type of

rationality, that which serves its own interests. Consequently

it also fails to systematically develop the idea that stakeholding

might serve a self-critical purpose and might to this end be driven by different rationalities

and corresponding action orientations and reference systems.

In the terms of our three-level concept of rational practice

(cf. Table 2 above), it would indeed make a fundamental difference

if corporate managers would approach stakeholders not only with a strategic but

also, and primarily, with a communicative concept of rationality

in mind. So long as stakeholding

relies on an unquestioned strategic concept of rationality,

it will

deal inadequately with the normative level of management and

thereby forsakes much of its potential for improving

management practice. Which after all is what stakeholder theory,

by advancing a supposed alternative to the

classical, economic and managerialist theory of the firm, was

meant

to achieve in the first place.

Second

example: the

"open systems" fallacy A

second example is offered by the so-called open systems approach

in systems thinking. There is a widespread belief in the systems

literature that an "open systems" perspective is more

conducive to societally rational decision making than are conventional

closed systems models. But once again, like in the previous

example, we are facing a claim that

in practice turns out

to be misleading, due to its not being grounded in a clear conception

of the rationality concepts at issue. I analyzed this "open systems fallacy," as

I call it, on three earlier

occasions7) and found it a useful way to explain

one of the core ideas of my work on "critical systems heuristics"

(CSH):

"Open,"

in contrast to "closed," systems models consider the

social environment of the system; but so long as the system's

effectiveness remains the only point of reference, the consideration

of environmental factors does nothing to increase the social

rationality of a systems design. In fact, if the normative orientation

of the system in question is socially irrational, open systems

planning will merely add to the socially irrational effects

of closed systems planning. For instance, when applied to the

planning of private enterprise, the open systems perspective

only

increases the private (capital-oriented) rationality of the

enterprise by expanding its control over the environmental,

societal determinants of its economic success, without regard

for the social costs that such control may impose upon third

parties.

Generally speaking,

a one-dimensional expansion of the reach of functional systems

rationality that is not embedded in a simultaneous expansion

of communicative rationality threatens to pervert the critically

heuristic purpose of systems thinking – to avoid the trap of

suboptimization and to consider critically the whole-systems

implications of any system design – into a mere heuristics of

systems purposes. This means that it is no longer "the

system" and the boundary judgments constitutive of it that

are considered as the problem; instead, the problems of the

system are now investigated. (Ulrich, 1988, p. 156, orig.

italics; with

reference to Ulrich, 1983, p. 299)

Not

unlike what has happened in strategic management theory and management

education, as

illustrated above by the example of so-called stakeholder theory,

systems thinking has become seriously impoverished as it has

lost sight of the other, non-utilitarian dimension of rationality,

a rationality perspective that we have characterized above in terms of social rather than

nonsocial orientation (M. Weber), communicative rather than success-oriented rationality

(Habermas),

or in Kantian terms also as theoretical-instrumental vs. practical-normative

reasoning. The two fields of management thought and systems

thinking also have in common that they both have been influential,

in the past few decades, in shaping our contemporary notions

of good and rational practice – so much so that an effective handling of the

many pressing problems of our epoch is now almost synonymous

with calls for more systemic thinking and for stakeholder management.

However, the promise of these two approaches is unlikely to

be fulfilled so long as the underlying rationality concepts are

impoverished.

Accordingly

imperative it is that the two-dimensional nature of rationality

receive more attention and become an integral part of the "open

systems" approach, no less than of stakeholder management.

This should happen

in a manner that would clarify the

mutual relationship of the two dimensions and strike a better

balance between them, that is, strengthen the communicative

dimension and with it the critically-normative issues that

it entails. As long as we merely see in the latter dimension

an added consideration that is "nice to have" but, regrettably, often clashes with the

need for successful action under pressures of time and money, little will change. Since the two

dimensions often clash, it is indeed difficult to think and argue

clearly and consistently about what constitutes good and rational practice.

Again a Kantian handling of the two dimensions gives us the

crucial hint: we can avoid unresolved rationality conflicts between them by bringing them into a vertical order,

so that their relationship and ranking become clear and do justice to

their nature or to what Kant (1786) calls the primacy of

practical reason. In everyday terms we might speak of the

means character of theoretical-instrumental

reason as related to the selection of ends that

must inform it and which in turn is to be guided

by practical-normative (including moral) reasoning and corresponding,

critically-normative discourse.

A multi-level conception

of rational practice as proposed in Table 2 offers a relevant,

practical framework for such two-dimensional systems thinking,

lest it remain a mere ideal. It

frees "open" systems thinking from being tacitly and

unquestioningly tied to a merely instrumental, success-oriented

concept of rationality; a concept of rationality that extends

the reference system from S to E but has no grasp of A, and which

for this reason also achieves little in the way of bringing into play the level of

communicative rationality. The crucial point, as we have well

understood by now, is that a mere expansion

of systems boundaries from S to E does not at all achieve a

change of the rationality perspective at work; for the

assumed reference systems for measuring successful and rational

action remains the same (S/E). Only the conceptual move to a different

reference system, the context of application (A), implies a

substantial shift of the rationality perspective at work; which

is what the suggested framework achieves with the move to the

third level of communicative rationality.

Generally speaking, then,

reflective practice calls not only for an

extension of our horizon of considerations but also for a conscious change

of the standpoint from which we seek to extend it. A mere expansion

of systems boundaries does not achieve this, as the underlying

rationality remains basically the same. Within a framework of conventional

systems thinking, chances are that an expanded "systems

rationality" (sic) will remain focused on the

success of the system of interest. It will thus tend to remain

subject to a strategic (i.e., utilitarian) rather than communicative

(critically-normative) handling of the social aspects of the situation.

The open systems fallacy occurs when our systems thinking aims

at an expansion of rationality without being embedded in a reflective

and communicative effort of challenging the notions of

rationality in play (cf. Ulrich, 1988, p. 156f).

Open

systems thinking that understands the issue becomes critical

systems thinking. Its methodological focus will

be on systematically questioning the different reference systems – the sets

of boundary judgments, that is – that inform the "facts"

and "values" (or the considerations and concerns)

taken to be relevant for judging situations and assessing good and rational

action. This is of course what CSH's core principle and major

tool of boundary critique is all about. By explicitly

integrating the concept of boundary critique into the three-level

concept of rational practice (an aspect that was still only

implicit in the framework's earlier versions of 1988, 2001,

and 2012), I hope that both concepts as well as their interdependence

have gained in clarity and critically-heuristic power, so that

they can support one another in the never ending quest for good

and reflective practice.

I

would like to conclude this discussion on the meaning and use

of reference systems in boundary critique with a hint at one

more methodological principle that is apt to guide critically-normative

practice along the lines suggested in this essay, I call it

the principle of critical

vertical integration of rationalization levels.

I adopt it, once again, from an earlier account (Ulrich, 2012b,

pp. 37-39).

Final

consideration: the principle of critical vertical integration

The term "vertical integration"

was to my knowledge first used by Erich Jantsch (1969a, p. 54f;

1969b, p. 190f) in

the context of technological forecasting and planning. He used

it to

refer to the integration of all its tasks – "activities"

or "functions,"

as he called them, such as exploring and assessing existent technologies;

anticipating and designing technological futures; and defining

objectives and policies for the "joint systems of society

and technology" (p. 8) – within a systems-theoretically

and scientifically based framework of policy sciences,

a field emerging in the 1950s and 60s (the seminal publication is Lerner and Lasswell, 1951).

Jantsch calls such an integration of forecasting and planning

functions "vertical," in distinction to the need for

considering, in each stage of technology development, the larger

context of the different

subsystems involved (man-technology, nature-technology, and

society-technology), to which he referred as "horizontal"

integration.

In

a slightly broader perspective, exploring the integration of

human design with an evolutionary perspective, Jantsch (1975, pp. 123, 209, 224) also speaks of "vertical centering," in a sense that

comes closer to what I mean with the vertical

integration of rationality levels. I can best explain my intention

by means of a graph that I equally owe to Jantsch (esp. 1975, p. 209).

Adapting it to our present aim of grounding the notion of rational

practice in practical philosophy rather than in management and

planning theory (along with systems thinking), and consequently

integrating the level of communicative rationality, we get the

following scheme (Fig. 6).

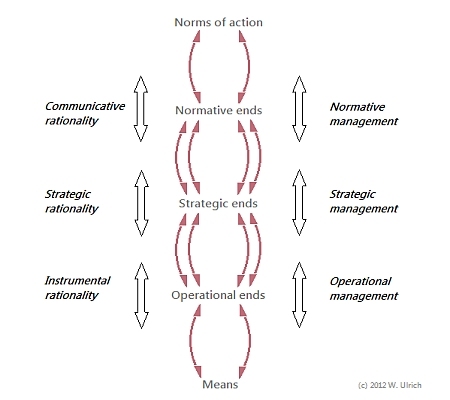

Fig. 6: The principle of vertical integration of rationalization

levels

"Critical

vertical integration" is a major principle that helps to

understand and apply the three-level concept of rational practice

proposed above properly. (Source:

adapted from Jantsch, 1975, p. 209, and Ulrich, 1975, p. 75)

The graphic

part of the scheme (but not the revised text) betrays its origin in cybernetic thinking and more specifically,

in Ozbekhan's (1969, p. 132f) notion

of "controlling feedback" loops, according to which

"each distinct level of action is controlled by feedback

emanating from a different level of the hierarchy" – the

idea that provided the inspiration for Jantsch's original graph. In my own

understanding of such integrative multi-level thinking, Ozbekhan's

and Jantsch's planning levels become levels

of rational practice in general. As the previous discussion should also

have made clear, I do not follow Ozbekhan and Jantsch

in their cybernetic rather than moral and political

understanding of "control." The

point is not

to adapt plans or actions to supposedly objective or

natural requirements of the planning "environment" (reference

system: E)

but rather, to subject them to the views and values of those

who may have to live with the consequences (reference system:

A) – the communicative

dimension of rationality. Accordingly, the different

levels of thought are to guide rationality critique (including

boundary critique) rather than just managerial control of "turbulent"

environments so as to achieve "organizational stability,"

as a famous concept of the epoch had it (Emery and Trist, 1969,

pp. 248-253).

The fact

that the idea of communicative

rationality was not available to Ozbekhan and Jantsch at the

time may explain why their frameworks for technological planning

and policy "sciences" remain strangely apolitical

and do not (or at least, not systematically) take up the ethical

and moral

questions involved, despite frequent references

to values and "normative" forms of planning. Again,

the difference is that Ozbekhan and Jantsch did not ground their

notion of rational policy-making in practical philosophy but

on the contrary, aimed to extend the reach of science into practical-normative

territory (compare my discussion,

in Ulrich, 2012a, pp. 6-9, of these

two opposite approaches to improving practice).

Where

I agree with Jantsch and Ozbekhan is that integrative multi-level

thinking, and thus (in our case) well-understood instrumental,

strategic, and communicative rationalization of practice, should

always move (or perhaps better, communicate) between and across the different levels at which ends and means,

and with them also values and consequences, can be defined and

questioned. Only thus can each level of rationalization infuse meaning (cf.

Ozebekhan, 1969, p. 133) into the other levels, whether

(as I'd like to add) in the form of direction (e.g., guidance,

support) or challenge (e.g., questioning of reference systems,

unfolding of selectivity and partiality). Consequently, each of our three levels of rational

practice also call for examination (and implicitly, again, for

communication) from both a top-down and a bottom-up

perspective. To handle the three levels reflectively, we therefore need to conceptualize means and ends

at no less than five levels, as suggested by the middle

column in Fig. 6 above:

- Norms

of action: highest standards or principles of action

(e.g., moral and democratic

principles); they shape our values and ideals.

- Normative

ends: standards of improvement defined by personal

and institutional values and by related notions of intended

consequences; they shape our policies.

- Strategic

ends: objectives defined by policies; they shape

our strategies and tactics of action.

- Operational

ends: goals defined by strategies and tactics;

they shape specific operations or procedures

of action. And finally,

- Means:

basic resources defined by available sources of support;

they shape the feasibility and efficiency

of action.

We

may then understand our three levels of rational practice to

function as communication channels or platforms, as intersections

at which different needs and notions of rationalizations meet

and can convey meaning and challenges to one another. Such communication

across systems levels or, implicitly, across the boundaries

of different reference systems, is indispensable with a view

to recognition and integration of competing or clashing rationality

requirements. We

may consequently also capture the

idea of a mandatory process of moving up and down the hierarchy

by referring to the three rationalization levels

as integrative levels, a concept that to my knowledge

Feiblemann (1954)

was first to explain systematically, although still in a context

of mainly functional thinking (e.g., in biology and ecology).

In the present context I understand integrative levels as conceptual

levels of rationality that gain their full meaning and validity

only in the light of a combined, or "integrative," multi-level perspective. The practical way to implement this

idea is by an iterative process of vertical centering:

each level

is at regular intervals (iteratively rather than permanently) to

be in the center

of systematic review both from above and from below.

This

way of visualizing and describing the idea of vertical integration should also

remind us that each of