Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly

Formerly "Picture of the Month"

July-August

2009 (Cloudspotter's Summer Break)

Reading Habermas in the Garden Chair

Cloudspotter's summer break Summer's here. Time for sun, sandals, shorts, and slowing down. Time also for some reading, relaxing, and reflecting (R3). So, if you wonder about the fate of Habermas in my "Reflections on Reflective Practice" series, I can report that I am busy reading Him, relaxing in the garden chair! What about the reflecting part of my triple-R (R3), you wonder? Well, that's what this Bimonthly is about.

You are not thrilled? Why, you mean you insist on having a summer break, too? Fair enough. Go and have your break, and then return in September to read about Habermas, rather than reading about my reading him now. But just before you leave, since you absolutely don't want to read this page, may I suggest that you briefly look at it. The thing is, I try to practice what I preach. Sitting in the garden chair as I am, I am hunting not only for Habermasian ideas these days but also for clouds. It's not that reading Habermas can occasionally be a clouded experience. Yes it can, but that is true whether you are sitting in your garden chair or not. What I mean is that as a confessed cloudspotter and amateur cloud photographer (see Ulrich, 2008), I can have a break simply by raising my eyes towards the heavens. Or I walk through the countryside near our home and watch out for some interesting clouds. Now in summer the sky is replete with collector's items, if only you care to look and carry your camera. Perhaps I may help you discover a new hobby that gets you into summer break mood, by sharing with you some of my recent summer cloud pictures? Ideally, you might then grab your camera and become a cloud spotter & photographer yourself, but it's not a condition. Nor is it a condition that you read any further in this page. Here is your chance to escape:

![]()

![]()

![]()

For those who are still with me, here is my progress report on reading Habermas.

Reading Habermas in the garden chair, thirty years later Habermas is the third of my "big three" of practical philosophy, after Aristotle (Ulrich, 2009a) and Kant (Ulrich, 2009b). Some 30 years have passed since I first studied Habermas in some detail and also was fortunate enough to meet him personally. Although I have kept reading him ever since, it is certainly an interesting experience to return to my roots and read him anew, against the background of my current work. It provides an occasion to have a serious look at his major recent publications, among them Truth and Justification (2003, enlarged German ed. 2004) and the brand new collection Philosophische Texte (5 vols., 2009). In addition, I am re-reading some of his earlier writings, particularly the books Communication and the Evolution of Society (1979), Theory of Communicative Action (2 vols., 1984 and 1987), and Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action (1990), both to refresh my memory and to see in what ways I read them differently now.

It's still a daunting task to try and overview such a wide-ranging and difficult philosophical work. Fortunately, summer affords me some extra time; moreover, the purpose of my present review of practical philosophy – the idea of mobilizing it as a third pillar of reflective practice – provides a helpful focus. Also, reading Habermas productively now is perhaps not quite as difficult as it was thirty years ago, at the outset of my academic path; yet it is hardly less rewarding. There is still this unique combination of scholarship and vision that I find attractive in Habermas. His scholarship remains an inspiring and much-needed example of forceful and differentiated argumentation. What a difference it makes to the mass of dull and sloppy writing that faces us in Academia today!

Grasping the central vision I have always found it helpful, in facing the overpowering erudition of Habermas, to remind me of the essential vision that motivates his work. I may even owe it to my repeated experience of reading Habermas, in fact, that I discovered how much it helps in reading any demanding work to try to grasp its underlying central vision. This is certainly true with Habermas. The insight remained at an intuitive, almost unconscious level though, until one day I found it spelled out beautifully in a lecture of the American pragmatist William James:

«Any

author is easy if you can catch the center of his vision.»

(James,

1977, p. 44)

For me, the center of Habermas' vision is rooted in the Kantian spirit of enlightenment (thinking for oneself); of emancipation (striving for personal autonomy, maturity, and responsibility); and of republicanism in its most basic sense (caring about the res publica). As I see it, Habermas translates this Kantian spirit into contemporary categories of critical discourse, of a functioning public sphere, active citizenship, equal opportunities, democratically legitimated rule of law, deliberative democracy, civil society, global citizenship, modernity, and so on; ideas that I not only find deeply ingrained in his writings but to which I also feel a strong personal affinity. Although I may never be able to fully master all the scholarly resources that Habermas mobilizes for the job, I feel I do understand the genuinely liberal and democratic spirit of his work, as well as its essential roots in Kant's vision of modernity, the never-ending quest for an enlightened and open society.

The hint I wish to give you, to be sure, is not that you should adopt this or any other specific understanding, but rather that you should discover your own notion of Habermas' central vision, so that you may then find it easier to deal with his overpowering scholarship. The point is not to approach Habermas with any idée fixe or prejudgment of what his effort is all about, but to encounter him with an open mind, looking out for the central vision that speaks to you in his writings. If you do approach Habermas in this way, I am confident you will find it a bit easier to read him; you will also quickly discover that Habermas' philosophy has little to do with the wholesale Marxist ideology that superficial commentators keep ascribing to him, for whom everything "critical" is apparently equal to Marxism; an allegation that also ignores the fact that Habermas has dealt carefully with an impressive range of contemporary philosophical currents, from critical social theory (Horkheimer, Adorno) to critical rationalism (Popper) and social systems theory (Parsons, Weber, Luhmann), from phenomenology (Dilthey, Husserl, Schütz) to language analysis (Chomsky, Austin, Searle), and from hermeneutics (Heidegger, Gadamer) to pragmatism (Peirce, Rorty) and postmodernism (Foucault, Derrida), to mention just a few main sources. Through his careful analysis and combination of such varied philosophical sources with the mentioned democratic ideas, Habermas remains for me one of our epoch's most forceful philosophical advocates of democracy.

What's changing? It seems to me I note some interesting, though subtle, changes of emphasis in Habermas' work, changes that seem to support rather than question the nuances to some of his basic tenets and the somewhat different views of critical practice that informed my work on Critical Heuristics, notwithstanding the important inspiration it owes to Habermas. I am thinking, for example, of his partial revision of the way he had originally tied the communicative turn of critical reason to an "ideal speech situation" and a "consensus theory of truth," with the result that his notion of discursively enlightened social practice was rather one-sidedly located within the boundaries of reason. Empirical and contextual considerations seem to gain a little more weight meanwhile, whereby it is not easy for me to say to what extent this is due to my different reading of Habermas now and to what extent it reflects an actual change in his thinking (I assume both aspects play a role). I am equally thinking of the notion of "discourse ethics," which appears to become a bit more open than before, in the sense of giving more room to issues of grounding actual ethical practice, or to what in the body of literature around discourse ethics is now increasingly (although perhaps somewhat misleadingly) described as the unsolved "problem of application" of discourse ethics (an issue I have discussed in Ulrich, 2006). As I argued already in my review of Habermas in Critical Heuristics (Ulrich, 1983, Ch. 5, esp. pp. 130n [note 25] and 162-172, although I prefer to put some of those early observations in slightly different words today), Habermas might originally have tied his conception of rational practice a bit too closely to universal and formal standards of "pure" communicative rationality, leaving insufficient systematic space for more contextual and material-pragmatic considerations.1)

My focus on critical heuristics of social practice, rather than on critical theory of society, was indeed motivated by a hope to overcome what I saw as a relative neglect of the pragmatic and contextual roots of critical practice in Habermas' understanding of the communicative turn, and of the issues of practicability that such a neglect was bound to raise (see the entire section "Conclusions: Critical Theory or Critical Heuristics?" of the 1983 review, pp. 153-172). It is with interest, therefore, that I observe some subtle but important changes in this respect. They not only are distinctive of a philosopher who has never stopped to question his own ideas; they are also helpful and encouraging to me with a view to pursuing the idea that philosophy in practice, properly informed by philosophy of practice but not identical with it, might furnish a much-needed (but thus far largely missing) pillar of reflective practice.2)

Challenges of quality and quantity My experience in reading Habermas is changing in some other respects, too. I may be a little less impressed (and patient) today than I was thirty years ago with the long-winded, often complex and laborious writing style that Habermas cultivates in the typical fashion of German erudition. The older I grow, the more I tend to appreciate the virtue of simplicity; the art of saying things as accurately as necessary, yet as simply as possible. The English language seems to encourage a simpler and more flowing writing style than German; so much so that I find myself reading Habermas in English whenever good translations are available, and consult the original text only to check the accuracy of both, the translation and my grasp of Habermas' meaning. One might regret that despite the important influence that Anglo-Saxon writers have had on Habermas' thinking, they apparently have not had a similarly important influence on his writing style.

But then, what is true in other fields may not be entirely wrong for philosophy: we probably cannot have the cake and eat it. That is, we should perhaps not expect to be able to learn from the outstanding erudition and sophistication of this writer yet have it all prepared in bite-sized pieces, as it were. Scholarly accuracy has its price.

In addition to the peculiarities of German academic writing at which I have hinted, it is of course equally essential to recognize that the subject of Habermas' social theorizing and practical philosophy – How we can we ground social science and critical practice philosophically and methodologically? – is intrinsically difficult. Just think of the enormous gap to bridge between the worlds of academic philosophy and everyday social practice (including the practice of research and professional practice). It is thus to be expected that such work does not lend itself to easy simplification and application, whether on the side of authors or on the side of readers. I find it certainly refreshing that Habermas, confronted years ago by an interviewer with the question of how we might reasonably practice the idea of critical science today, avowed with disarming honesty and accuracy:

«This

entire issue isn't altogether clear to me either.»

(Habermas,

1985, p. 167, my transl.)

Nobody can possibly claim to master the subject entirely, given that we are dealing with unresolved philosophical issues; and it is again distinctive of a critical mind like Jurgen Habermas that he does not try to make it look as if he could. So much is certain: new ideas are required if we are to assure not only philosophical credibility but also practicability to the quest for practical reason and critical practice; but when ideas are really new, they cannot always be formulated from the outset as simply as we may wish, as we are still struggling with them. Simplicity must come at the end, not at the beginning. That is what keeps me reading.

|

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

![]()

![]()

![]()

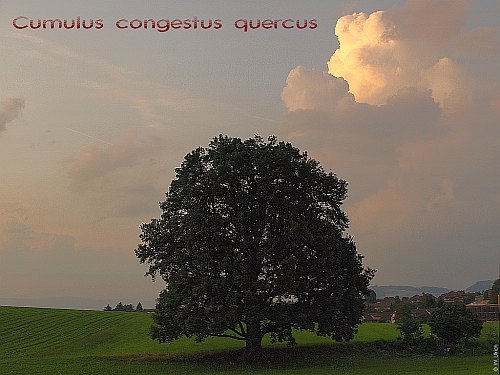

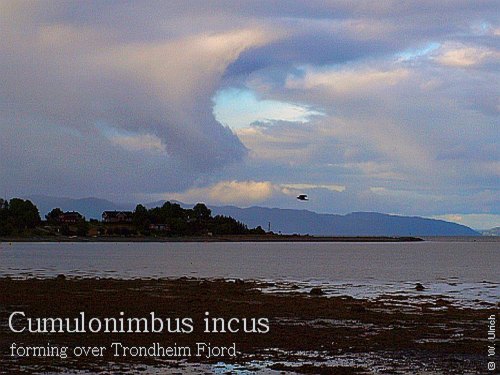

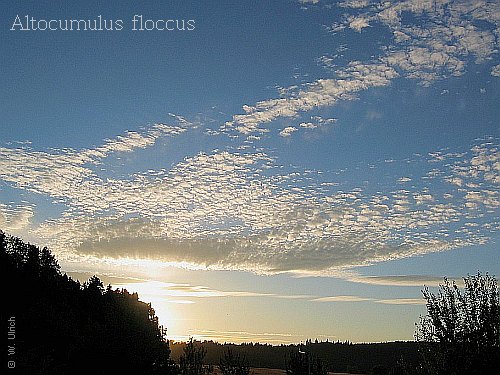

Summer clouds I've said enough; clouds, take over! Although our writing and reading experience is often more clouded than we'd like – for now, the clouds are to give you a moment of pure enjoyment and relaxation.

Clouds, so proclaims the Manifesto of The Cloud Appreciation Society, are "Nature’s poetry, and the most egalitarian of her displays, since everyone can have a fantastic view of them." I agree. Could one wish for more inspiring, yet tranquil and relaxing company in a summer dedicated to reading Habermas?

Let me have my summer break, then, while leaving you with my cloud pictures. See you later this year! Yours with best wishes for a gorgeous summer break!

W. Ulrich

P.S.: It's OK if you spend this summer reading Pretor-Pinney (2006) rather than Habermas. [BACK]

(Click

on pictures to enlarge them)

And ... dont' forget to see the main bimonthly picture at the bottom of the page!

Notes

1) A basic distinction that I still find useful for understanding the development of Habermas' work, from his original framework of a theory of knowledge-constitutive interests to a discourse theory of rational practice tied to ideal conditions of rational motivation and consensus, is that between the so-called a priori of argumentation and the a priori of experience; see Ulrich, 1983, pp. 114f, 152-158, and 163-166. [BACK]

2) We touch here upon a distinction that I have suggested earlier in this series to structure our step-by-step approach to practical philosophy, I mean the distinction between philosophy of practice and philosophy in practice (Ulrich, 2009a and 2009b). To do justice to Habermas, we probably need to recognize his work primarily as a (brilliant) example of philosophy of practice, which means we can hardly do justice to it if we try to read it with a view to immediate application in everyday practice. Our current effort, the reader will remember, is aimed at philosophy in practice; however, we currently are still trying to prepare the ground theoretically and methodologically, by learning from major philosophers of practice. [BACK]

References

Habermas, J. (1979). Communication and the Evolution of Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1984). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 2: The Critique of Functionalist Reason. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Habermas, J. (1985) Dialektik der Rationalisierung, in J. Habermas, Die Neue Unübersichtlichkeit, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, pp. 167-212. Orig. published as "Dialektik der Rationalisierung: Jürgen Habermas im Gespräch mit Axel Honneth, Eberhard Knödler-Bonte und Arno Widmann" in Aesthetik und Kommunikation, No. 45/46, 1981. Engl. transl.: The dialectics of rationalization: an interview with Jurgen Habermas, Telos, 49, Fall Issue, 1981; reprinted in P. Dews (ed.), Autonomy & Solidarity: Interviews with Jurgen Habermas, London: Verso, 1992, pp. 95-130.

Habermas, J. (1990). Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. German orig.: Moralbewussstein und kommunikatives Handeln, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1983.

Habermas, J. (2003). Truth and Justification. Boston, MA: MIT Press. German orig.: Wahrheit und Rechtfertigung: Philosophische Aufsätze. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp; enlarged paperback ed. (orig. 1999). (Note: The English translation, apparently due to its being based on the original 1999 edition, does not contain the two important chapters 2 and 5 of the enlarged German edition.)

Habermas, J. (2009). Philosophische Texte. 5 vols. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

James,

W. (1977). Hegel and his method. Lecture III, in W. James, A Pluralistic

Universe, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[HTML] http://www.fullbooks.com/A-Pluralistic-Universe1.html

Pretor-Pinney, G. (2006). The Cloudspotter's Guide: The Science, History, and Culture of Clouds. London: Hodder & Stoughton. [BACK]

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt, pb. reprint ed. New York: Wiley, 1994.

Ulrich, W. (2006). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics. In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business Ethics, Vol. I, Oxford, UK: Peter Lang Academic Publishers, 2006, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich,

W. (2008). Practical reason: drawing the future into the

present. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, November-December 2008.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2008.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_november2008.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2009a). Philosophy of

practice and Aristotelian virtue ethics. Reflections

on reflective practice (4/7). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, January-February 2009.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2009.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_january2009.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2009b). Practical

reason and rational ethics: Kant. Reflections

on reflective practice (5/7). Ulrich's

Bimonthly, March-April 2009.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2009.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2009.pdf

This Bimonthly's main picture: dove-shaped altocumulus Digital photograph taken on 11 August 2007 around 16:15 p.m. near Bern, Switzerland. Altocumulus in combination with a contrail formed a dove of rare perfection and size. My wife and I had just begun a leisurely walk near our home, when the phenomenon occurred. It covered such a huge area of the sky that it filled the entire 28 mm wide-angle range (small-picture equivalent) of the lens that I had mounted on the camera. There would have been no time to change the lens, as the phenomenon was moving fast and quickly lost its perfect shape. Click to enlarge. Technical details: ISO 100, aperture f/3.5, shutter speed 1/200, focal length 14 mm (equivalent to 28 mm with a conventional 35 mm camera), original resolution 3648 x 2736 pixels. The smaller picture was reduced to 700 x 525 pixels and compressed to 56 KB, the larger picture to 1024 x 768 pixels and 98 KB.

|

July 2009 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

August 2009 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

„Clouds are Nature’s poetry, and the most egalitarian of her displays, since everyone can have a fantastic view of them.”

From the "Manifesto of the Cloud Appreciation Society" (Pretor-Pinney, 2006, p. 11)

Notepad for capturing personal thoughts »

|

Personal notes:

Write

down your thoughts before

you forget them! |

|

Last updated 22 Jun 2014 (title layout), 10 July 2009

(text); first published 9 July

2009

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_july2009.html