|

|

|

Part 6c: Discourse ethics and deliberative

democracy, or the difficult path

to communicative practice – Habermas 3

(1st half) In

two previous essays of the series of reflections

on reflective practice, we examined the methodological foundations

of Habermas' practical philosophy. Practical philosophy is concerned

with the nature of human practice and ways to improve it, as

distinguished from the attempt of theoretical philosophy to

help us understand the nature of the world and of our knowledge

about it. We first focused on Habermas'

formal pragmatics,

an account of the deep

structures of rational communication (Ulrich,

2009c), and then on what we called the Toulmin-Habermas model

of argumentation, a pragmatic

logic of cogent argumentation (Ulrich, 2009d). The

former explains the general validity basis of speech and thus

of communicatively secured

mutual understanding, whereas the latter aims at a general model

of discourse and thus also of practical discourse in the sense

in which "practical" is understood in practical philosophy,

meaning as much as raising, or being about, normative questions. The two models embody closely interdependent

theoretical

attempts to elucidate the general pragmatic presuppositions of communicative rationality,

that is, to explain how practice can in principle be rationalized

through dialogical means

(see, e.g., Habermas, 1984, pp. 25 and 34; 1998, p. 44; 2009, Vol. 2,

p. 266). As a convenient term for both models, I will speak of the formal-pragmatic

framework (or model) of rational practice.

The

central question to which we now turn is this: Does

this framework lend itself to practice, and to the extent it

is not practicable without further ado, how might we pragmatize

it? To put it differently, the

question that interests us particularly in this third part is

whether the practical philosophy of Habermas is merely an original

and insightful theory of practice or whether it also

provides a theory for practice, a framework of thought

about good practice that allows of discursive realization. Since

our overall aim in this series is to revive the almost forgotten idea

of practical reason as a missing element in contemporary notions

of reflective

professional practice, we can also formulate the above

question as follows: Is

it possible to employ the formal-pragmatic

framework so as to breathe new life into the concept of practical

reason? I

suggest to discuss this question by considering two major applications

of

the framework

that promise to be relevant to the aim of promoting reflective

professional practice:

- Discourse

ethics: What light does formal pragmatics

shed on the importance and possibility of moral reasoning with a view to recovering

the ethical dimension of rational practice?

- Deliberative

democracy: What light does formal pragmatics shed

on

the political and legal control of power

with a view to strengthening the democratic constitution of modern societies?

For

the first question we can partly draw on two previous essays

in which we explored Habermas' notion

of discourse ethics

(see Ulrich, 2010a and

b). Although they are not part

of the current series of reflections on reflective practice,

they were indeed written with a view to

preparing the present effort, so that we need not burden

the current analysis with so much theoretical background discussion.

It will be worthwhile though to recall some of the basic

earlier conjectures on the idea of a discursive grounding of

ethical practice. The focus, however, will be on the more specific

question:

Can discourse ethics become a relevant part of actual professional

practice?

The second question aims at the need for grounding good

practice not only ethically but also democratically, that is,

in democratically institutionalized processes of decision-making

about matters of not purely private concern. We need

to understand the ways in which an adequate ethical grounding

of practice relates to its democratic grounding, and how a formal-pragmatic

framework might help us in doing justice to this interdependence.

Can there be an ethically relevant and practicable concept

of democracy as discursive practice?

It

should be clear though that the institutional issues involved

in a democratic grounding of professional practice reach deeply

into the fields of political philosophy, philosophy of law,

and theory of democracy, and thus beyond practical philosophy.

Since our main interest in this series is in the practical-philosophical

leg of reflective professional practice, I will address the

topic of deliberative democracy in a relatively cursory manner

and only inasmuch as it plays a complementary role to the discussion

of discourse ethics; the focus of the present Bimonthly

will be on discourse ethics.

Discourse

ethics Discourse

ethics is Habermas' answer to Kant's practical philosophy. It aims at a contemporary

interpretation of the tradition of rational ethics and its core

idea of grounding ethics in reason rather than in personal virtue,

social custom and convention, or religious faith and authority. At the same

time, discourse ethics is a major application and to some extent

also an extension of

the basic methodological framework that Habermas proposes as

a basis for critical social theory and practice, formal pragmatics.

We can thus introduce discourse ethics in two ways: first,

by analyzing its basic motives and conjectures against

the background of Kant's conception of rational ethics as we

discussed it previously (see Ulrich, 2009b, 2010a, b; in addition,

Ulrich, 2011c, offers a concise introduction to Kant's rational

ethics);

and second, by understanding it as a development of Habermas' framework

of formal pragmatics as we equally discussed it earlier (see Ulrich,

2009c and d). We will follow both paths. Our main interest will be in discussing

discourse ethics as a special application of formal pragmatics,

while situating discourse ethics in the tradition of rational

ethics will be useful to prepare us for that discussion. First,

however, we need to clarify some basic

terminological issues, concerning the relationship of ethical

to moral questions on the one hand and of practical to pragmatic

reasoning on the other hand.

Some

terminological basics

Ethical and moral

questions General

usage subsumes under "ethics" two different types

of normative issues. On the one hand, there is the basic issue

of how people's notions of the good – their

worldviews and values – condition what they consider to be desirable ways

to live and act, say, with a view to "improving" an unsatisfactory

situation or ensuring "good" professional practice.

On the other hand, there is the more specific issue of how people

try to handle conflicting notions of the good,

an issue that in the face of increasing cultural diversity and

ethical pluralism becomes ever more important. Both issues may be called "ethical," but

only the second is also "moral"; it raises the

question of what kind of standards (if any) there are to resolve

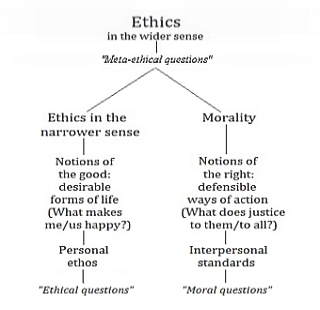

ethical conflicts. We thus arrive at

three concepts of ethics as shown in Fig. 5. Ethics as

a generic term includes all questions of value judgment, including

reflections on the nature of such questions, that is, ethical

issues and judgments (meta-ethical questions). In the

present essay, we

will focus on the two more specific kinds of ethical issues

at the lower level of Fig. 5. They concern people's

personal notions of what is good

and desirable ("What makes us happy?") on the one

hand and interpersonal

notions of justice or fairness ("What is right?")

on the other hand.

For the sake of brevity and clarity, I will refer to

the first kind of issues as ethical questions and to

the second as moral questions.

Finally, the term evaluative

questions will refer to ethical issues that may include

ethics in the wider and the narrower sense but not moral questions,

while the term normative questions will also include

the latter.

Fig. 5: Concepts

of ethics: ethical and moral questions

The

narrower

concept of ethics appears to become more prominent recently.

In media discussions

for example, politicians nowadays talk of "ethical

and moral issues" as if it were a matter of course

to distinguish between the two and everyone understood

the difference (I doubt everybody does). The implicit idea seems to be that

due to different cultural backgrounds and personal experiences, people

have increasingly divergent views about good and desirable ways to live and hence,

that ethics in

the face of such value pluralism cannot make itself the

arbiter of right and wrong. Ethics is thus moving closer to

ethos,

a personal stance that we may or may not share with others but which we

cannot

meaningfully say to be right or wrong. Your way of life is just

that and it would be presumptuous for me to claim that my different

way of life is better.

Ethically alert readers are

bound to sniff danger here:

such ethical relativism threatens to undermine any solid basis

for rationally defensible, yet ethically grounded action. This

is why a second concept of ethics is needed, morality. Morality

is concerned with the ways an agent's personal ethics may clash

with that of other people and may affect their lives, by constraining their options to live and act in

accordance with their personal ethics. We are confronted

with a collective issue of reconciling different

notions of what is a proper way to live and to act. Moral

questions thus cannot avoid the issue of defining some basic interpersonal

standards for handling ethical clashes. That makes them

difficult questions. Such standards are not easy to find; they must arguably

deserve recognition by everyone who might face a similar situation, for example, because they treat people

with equal respect for their individual needs and values and

in this sense may count as impartial. To the extent such standards can

indeed be found, moral questions become rationally decidable

and in this respect are easier to handle than other ethical questions.

Whether a certain

action or action-related proposal is up to standard can then

be systematically

examined, for example,

by considering past experiences or anticipated consequences

of a proposed action and measuring them against such a moral

standard. Morality is the territory on which ethics and

rationality can meet and can support one another.

An

important methodological difference emerges here between moral

and other normative questions. We can argue about the moral implications

of an action with a view to determining whether a proposal is

right or wrong, but we can only reflect on the underlying

ethos and discuss it with a view to understanding people's assumptions,

say, about what would constitute an improvement of a specific situation

of concern to them. In short, we can dispute and

justify moral claims, but we can at best recognize (in the

double sense of understanding and tolerating) ethical claims.

Discourse ethics accordingly

focuses on moral questions, as the only kind of normative issues

that allow of rational decision-making. Insofar the name of discourse ethics is a misnomer. Discourse ethics

is neither a general method for discussing ethical questions

nor an ethical code

of conduct for discourse in general. Rather, it is a specific

piece of meta-ethical theorizing in the tradition of Kantian

rational ethics. Habermas really intends with it a new approach to moral theory,

understood as a general theory of moral action. A name such as "discourse

theory of morality" or "communicative moral philosophy"

would have expressed this intention more clearly. Not unlike other contemporary work on moral

philosophy written in this tradition, such as Baier's

(1958) account of the moral point of view, Rawl's (1971) theory

of justice, Hare's (1981) account of moral thinking, or Kohlberg's

(1981) theory of moral development, to name just a few

outstanding examples, it aims at clarifying the methodological foundations and formal properties of moral reasoning.

This theoretical aim is not to be confused with the different,

"applied" aim of explaining how the requirements of

moral reasoning thus

identified can

be met in practice, or what substantial norms of action an agent

should rely on in a specific situation.

In

one respect though, "discourse ethics"

is not an entirely ill-chosen name for Habermas' project: discourse

ethics indeed seeks

to ground the theory of moral action in an ethos of communicative practice.

It embodies a response to the ethical pluralism of our epoch that wants

us to rely on rationally motivated, argued reconciliation of interests

and value conflicts rather than on non-argumentative means such

as recourse to authority, power, or manipulation. At the bottom

of the moral aim of discourse ethics lies Habermas' overall ethical

vision of a communicative

rationalization of society. In this respect the impetus of discourse ethics reaches beyond moral theory,

towards a form of life that we may associate with an Enlightenment

ethos in the tradition of Kant. This is the ethos of citizens

who, because they see themselves as free and responsible

members of a community that offers space for a plurality

of forms of life, are prepared to settle conflicts with others

on the basis of mutual tolerance, respect, and

deliberation. So the name "discourse ethics," despite

the terminological

difficulty it raises, is indeed programmatic; it

stands for the double ambition of reconstructing moral

philosophy and promoting an ethos of communicative practice.

Practical

and pragmatic questions A second terminological difficulty

arises

from the close link between discourse ethics and communicative

practice. Communicative

practice faces not only ethical questions in the two senses

we have distinguished above, relating to "good" (desirable)

and "right" (just) ways to act, but also empirical

questions of "fact" (circumstances to be considered)

and "feasibility" (effective and purposive ways to

act). In his often-cited essay "On the pragmatic, the ethical,

and the moral employment of practical reason," Habermas

summarizes these different kinds of "practical" (i.e.,

action-related) problems under the question "What should I do?" and

aligns them with "moral, ethical, and pragmatic questions"

(1993a, p. 2 and 8f). Further, he

distinguishes a "pragmatic" from an ethical or moral

perspective by its orientation to a

"horizon of purposive rationality, its goal being to discover

appropriate techniques, strategies, or programs" (1993a, pp. 3 and 9). He also emphasizes that practical discourse

need not "neglect the calculation of consequences of actions

rightly emphasized by utilitarianism nor exclude from the sphere

of discursive problematization the questions of the good life

accorded prominence by classical ethics, abandoning them to

irrational emotional dispositions or decisions." (1993a,

p. 2)

We

can appreciate Habermas' intent: there is no need to

limit the relevance

of practical discourse and discourse ethics to any particular tradition

of ethical and/or moral thought. Nor should we as a matter of

principle immunize any kind of ethical assumptions or claims

against careful questioning and deliberation, by relegating

them from the outset to a sphere of nonrational acts of faith

only. Even so, we better try to avoid the terminological confusion that threatens here. In

particular, I do not think we should equate a pragmatic perspective

with purposive-rationality. The essence of pragmatic thinking

consists in considering the meaning and validity of a claim

in the light of its actual or potential consequences, which

does not imply a merely instrumental or strategic concept of

rationality at all, as little as it implies a merely utilitarian ethics. Well-understood

pragmatic thinking remains open to different notions of rationality

(including communicative rationality) and ethics (including

Aristotelian ethics and Kantian morality). Likewise, we better

avoid subsuming under practical questions each and all action-related

issues. The question "What should I do?" is philosophically

ambivalent; it stands for questions not only of practical reason

(i.e., normative issues) but also of theoretical reason (i.e.,

instrumental or strategic issues). Associating these with "practical" discourse may correspond

to an everyday usage of theses terms but runs counter to standard usage in practical philosophy, where "practical"

reason, following Aristotle and Kant, stands for a specifically

normative dimension of reason that is distinct from its theoretical-instrumental

dimension.

To be sure, the answers

we give to questions of feasibility

and purposiveness

may and usually do have normative implications, just as the answers we give

to ethical and moral questions may in turn raise instrumental

or strategic questions. In

discursive practice, theoretical-instrumental and practical-normative

questions tend to come up together. For instance, the choice

of means to achieve an end (an instrumental question of purposiveness) always

also entails normative questions (how do different means affect

different groups of concerned parties), just as the selection

of the ends to be reached (an ethical and often also moral question) raises questions of feasibility and purposiveness. Even so, it is essential

to distinguish between issues of "practical"

(i.e., normative) and "theoretical" (i.e., instrumental)

reason; for they pose different methodological demands. Thus seen, associating "practical" discourse

with all action-related question of the type "What should I do?"

is unfortunate. A more exact way of talking might have said

that the quest for rational practice (as distinguished

from practical reason)

raises different kinds of action-related or "What should we do?"

type

of questions,

some of which confront us primarily with issues of theoretical reason (What

is the feasible and purposive thing to do?) and others, with

issues of practical reason

(What is the good and right thing to do?).

Terminological

confusion threatens because Habermas, without saying so, switches between everyday and philosophical

usage of terms such as "should," "practical,"

and "pragmatic." While in everyday language these

terms are used loosely to refer to both normative and instrumental

or strategic forms of reasoning, in philosophical usage they refer to genuinely normative forms of reasoning only

and that is how we will employ them here.15) 16)

We will thus continue to associate "practical discourse" with

genuinely normative questions only. This excludes questions

of feasibility and purposiveness, which fall under the jurisdiction

of theoretical discourse; they may and usually will

come up in practical discourses, but they need to be clarified

by the specific means of theoretical-instrumental reasoning

and scientific discourse (think of tools such as feasibility

studies, cost-benefit analysis, forecasting, risk assessment,

strategic management, etc.). As soon as we enter into

such discussions of feasibility and purposiveness, we have in fact switched to theoretical

discourse. Conversely, inasmuch as theoretical-instrumental

questions entail normative questions, the latter of course fall

under the jurisdiction of genuinely practical reason and discourse

and thus are proper subjects of discourse ethics. Further, we will not equate "pragmatic"

reasoning with a particular focus on instrumental and strategic

questions; rather, we will continue to understand a pragmatic

perspective as encompassing all forms of theoretical-instrumental and

practical-normative reasoning inasmuch as they regard a claim's

consequences as the touchstone for assessing its meaning and validity.

This use of language is in line with Kant's distinction

between the "pure" and the "pragmatic" employment

of practical reason: both entail moral reasoning but

the former relies on a priori reasoning only, so that

its resulting rules of action are not conditioned by any empirical

contingencies, whereas the latter does consider empirical circumstances.

In short, practical reason is "pragmatic" whenever

it is not pure, but in either case its rationality is of a moral

kind (see Kant, 1787, B828, and the brief discussion in Ulrich,

2006b, p. 58f).

We are now ready to introduce the

essential ideas of discourse ethics, beginning as

announced with a short glimpse back at Kant's cognitive turn

of ethics.

Discourse

ethics and Kantian ethics

The cognitive

core of ethics Kant

saw the ultimate root of morality in the good will of mature,

responsible agents who act with respect for others and therefore

place

themselves in the situation of those concerned by an action. Such an understanding of

ethics confronts moral agents with major cognitive demands.

Agents need to understand the implications of their ways of

acting for other people as well as for the communities of which

they are part, along with other communities and ultimately the global human community,

now and in future. Further, it is

not good enough to have a "good will" and lean back;

a good will must also express itself in an active effort to

pursue the good, which in turn demands an effort of finding

out, through careful reflection and observation, what "good"

action means in specific situations.

As

we learned from Kant, agents who

are not willing to make such an effort will hardly be able for

long to guide and justify their

conduct without entangling themselves in contradictions.

An agent who egoistically acts without considering the implications

of his conduct for others, risks treating other people in

ways they do not want to be treated, for example, because they

hold different ethical and cultural values or because they

may have to bear adverse consequences. Such an agent tacitly claims to be entitled

to treat others in ways he or she would not want to be treated

by them, that is, without their consideration and respect for his

needs and values. We briefly considered the example of so-called

tax heavens (see Ulrich, 2009b, note 3, and Ulrich, 2010b. p. 22f): tax heavens allow banking secrecy

to facilitate tax evasion

on the part of the

citizens of other countries, yet they would not want their own citizens to

find shelter from paying taxes in these other countries. Or,

to use two of Kant's examples, a liar does not want others to

lie at him, just as a murderer does not want others to murder

himself.

The

immorality of such actions roots in the fact that agents

– whether consciously or not – claim for themselves exceptions

from principles they expect others to respect, or privileges they do not grant to other people. Accordingly

they cannot justify their conduct

except by exempting themselves from the implications of their

actions. They therefore cannot help but argue inconsistently,

by invoking norms or rules of conduct they do not respect themselves.

This is why they are bound to become caught up in contradictions.

"We cannot demand from others what we refuse to respect.

It is a practical impossibility." (Mead, 1934, p. 381).

It is, in fact, both an emotional and a logical impossibility:

those affected will feel moral indignation, and those involved

will be unable to argue consistently. This, in short, is why

Kant sought to give morality a rational foundation: one cannot shut one's eyes to the moral dimension

of action and still claim to have reason on one's side.

Kant

thus became the pioneer of rational ethics, the idea

that morality resides in the agent's moral alertness and

reflection rather than in some external authority such as tradition or convention, or

religious or political leaders who tell

us what is allowed and what is not. If there is any philosophical basis for

grounding ethics, Kant taught us, it is to be found in

reason's internal demands, that is, in those general structures and requirements of

rationality without which it cannot operate. For example, reason cannot help but regard itself as free;

it cannot allow itself to be inconsistent; and quite generally,

it needs to preserve its own integrity (cf. the earlier discussion in

Ulrich, 2009b, p. 9f).

Ever since, practical philosophy

has been the philosophical discipline that examines the question

of how moral

issues can be handled "with reason." There exists,

for Kant, a deep link between morality and rationality: we

cannot be moral without being reasonable. Ethical traditionalism

consequently gave way to ethical cognitivism; the moral authority

of custom, dogma, and power was replaced by the quality of the

agent's moral sense and reasoning or, to speak with

Baier (1958), by the agent's cultivating the moral point of view.

We

say of someone that he is a person of good will if he is always

prepared (should it be necessary) to enter, before acting, into

moral deliberation, that is to say, to work out what is, morally

speaking, the best course open to him, that is, the course supported

by the best moral reasons, and also prepared to act in accordance

with the outcome of such deliberations. (Baier, 1958, p. 82)

As

we further learned from Kant, the link between the moral and

the rational involves the idea of

moral universalization: our subjective maxims

or principles of action, and with them the normative implications

of what we claim and do, can be rationally justified to the

extent they are generalizable – generalizable, that is, in the strong

sense that we

not only may expect any mature (or "reasonable") person

to accept them (factual acceptance)

but also can explain

why they deserve being generally accepted (good grounds).

For example, as I have hinted above, they might deserve such recognition because they are impartial, that is, they

treat everyone according to the same criteria and do not privilege any particular

interests or (possibly hidden) private agenda. Accordingly, we should also be able to defend such

principles publicly and

to teach them generally across all cultures and customs

(see Ulrich,

2010c).17)

The

communicative turn of cognitivist ethics Kant's

way of tying morality to reason was ingenious and fruitful;

but it has its difficulties and in some respects I think

he methodologically overburdened it. What in Kant's epoch may have been a reasonable

demand – that agents of good will should consider all the implications

their ways of acting may have from the perspective of those

concerned – appears to become increasingly difficult in an age

of ethical pluralism and global interconnectedness.

Who in this complex world of ours can claim to anticipate and appreciate (let alone justify)

all the implications an action may have for all the parties possibly

affected in some way, here and there, now and in future? True,

Kant emphasized the overriding importance of the agent's

good will as compared to the importance of correctly

anticipating and appreciating all conceivable consequences;

even so, it is clear that our notions of what a "good will"

means in a specific situation of action originate in our perceptions

of the world we live in and in our previous accumulated

experience of the effects that our conduct and that of others

has had on that world we live in. Therein consists the cognitive

kernel of all ethics and morality, to which Kant drew

our attention more than anyone before.

To

some extent, one might argue, the historically increasing cognitive

burden of good-willed action is compensated for by the hugely

expanded knowledge and tools of inquiry and expertise that are

at our disposal today. This is indeed so. But there is another, even more fundamental difficulty: by formulating the core idea of rational ethics

as an abstract principle of moral universalization, Kant removed it

entirely from the context in which moral consciousness originates

in the first place, the social lifeworld

of interacting and communicating individuals in which mutual

recognition, respect, and responsibility can naturally

develop and unfold.

The

first critic who famously (and somewhat unjustly) accused Kant

of proposing a mere "moral formalism" that was removed

from the social context of moral consciousness, was of course

Hegel (1802, p. 331). Habermas (1973a,

p. 150; cf. 1990c, pp. 195f, 201-211) took up Hegel's critique

in an early discussion that anticipated some aspects of his later communication-theoretical

turn. Habermas found that Kant

indeed missed the essentially interactive and communicative nature of moral

practice from the outset. Moral practice is fundamentally constituted

by communicating individuals who out of mutual recognition and

respect try to coordinate their actions with reason rather than

with force. In one phrase, morality roots in a fundamentally

cooperative stance. As we might put it (not following Habermas),

the

essence of morality is cooperation. What Habermas (1973a,

p. 150) beautifully describes as morality's inherent utopia of "unbroken

intersubjectivity" is, I would argue, indeed implicit in

Kant's notion of good will. The problem is, by assuming that

agents of good will are both willing and able to put themselves

in the situation of everyone concerned, Kant's formulation of

the moral principle takes such unimpaired intersubjectivity for granted rather than showing

how it can be supported – so much so that in the end it does not

emerge as a methodological issue of moral theory at all,

much less as a challenge to moral practice.

Both

from the everyday perspective of a contemporary understanding

of responsible

practice and from

the theoretical perspective of formal

pragmatics as Habermas has elaborated it meanwhile, the categorical imperative really calls for

being freed from the "monological" straitjacket in which Kant

put it. Rather than conceiving of moral universalization as an

"exercise of abstraction" (Habermas, 1993b, p. 24,

cf. 1990c, p. 195),

we might situate it directly in communicative

contexts

in which

participants can voice their concerns authentically and

can challenge one another's assumptions and conclusions. From

an everyday perspective it is obvious that under modern

conditions of life characterized by ethical and cultural pluralism,

philosophy can no longer credibly play the role of an arbiter

and decree on behalf of ordinary people what are proper forms of life and

of conduct. Rather,

How

one lives one's life becomes the sole responsibility of socialized

individuals themselves and must be judged from the participant

perspective. Hence, what is capable of commanding universal

assent becomes restricted to the procedure of rational

will formation. (Habermas, 1993d, p. 150; different transl.

in 1992b, p. 248)

From a

formal-pragmatic perspective, the question arises of

how under contemporary conditions of ethical pluralism, rational

will formation about normative questions is still possible at all. The answer can only

be that rational ethics must limit its ambition to those normative

questions

that we have earlier called moral questions, that is, questions

that implicitly refer to generalizable standards and which accordingly,

to the extent such standards can be found, lend themselves to

interpersonally binding answers.

We

can't expect to find a generally binding answer when we ask

what is good for me or for us or for them; instead, we must

ask what is equally good for all. This "moral point

of view" throws a sharp, but narrow, spotlight that picks

out from the mass of evaluative questions practical conflicts

that can be resolved by appeal to a generalizable interest;

in other words, questions of justice. [Only these questions]

are so structured that they can be resolved equitably in the

equal interest of all. Moral judgments must meet with agreement

from the perspective of all those possibly affected and not,

as with ethical questions, merely from the perspective of some

individual's or group's self-understanding or worldview. Hence

moral theories, if they adopt a cognitivist approach, are essentially

theories of justice. (Habermas, 1993d, p. 151; different

transl. in 1992b, p. 248)

The

fundamental standard that the moral point of view brings into

play is the quest for impartial answers to moral

questions. The binding force of such answers originates in the

interpersonal acceptability and persuasiveness of ideas such

as reciprocity of behavior and expectations; respect for the

intrinsic autonomy and dignity of all individuals; equal consideration

for the different views and values of everyone concerned; fair treatment

for all; or in short, what Habermas refers to as "justice."

This, in a nutshell, is the basically simple, although in its philosophical

execution complex, change of perspective

introduced by the communicative turn of

ethics. The fundamental question that it entails is how interpersonally binding answers to moral questions can

be rationally identified and justified through communicative

interaction.

The

discursive turn of communicative ethics Readers

will remember from the previous two parts of this introduction

to the practical philosophy of Habermas that he calls interactions "communicative"

when they entail an obligation to redeem a claim discursively,

by relying on argumentative rather than nonargumentative

means. Here is a somewhat longer extract from his "Notes"

on discourse ethics that summarizes the main ideas:

I

call interactions communicative when the participants

coordinate their plans of actions consensually, with the agreement

reached at any point being evaluated in terms of the intersubjective

recognition of validity claims.…Further, I distinguish between

communicative and strategic action. Whereas in strategic action

one actor seeks to influence the behavior of another

by means of the threat of sanctions or the prospect of gratification

in order to cause the interaction to continue as the

first actor desires, in communicative action one actor seeks

rationally to motivate another by relying on [the

performative or regulative function of] his speech act.

The fact that a speaker can rationally

motivate a hearer … is due not to the validity of what he says

but to the speaker's guarantee that he will, if necessary, make

efforts to redeem the claim that the hearer has accepted.… As

soon as the hearer accepts the guarantee offered by the speaker,

obligations are assumed that have consequences for the interaction,

obligations that are contained in the meaning of what was said.

In the case of orders and directives, for instance, the obligations

to act hold primarily for the hearer, in the case of promises

and announcements, they hold for the speaker, in the case of

agreements and contracts, they are symmetrical, holding for both

parties, and in the case of substantive normative recommendations

and warnings, they hold asymmetrically for both parties.

… Owing to the fact that communication

oriented to reaching understanding has a validity basis, a speaker

can persuade a hearer to accept a speech-act offer by guaranteeing

that he will redeem a criticizable validity claim. In so doing,

he creates a binding/bonding effect between speaker and hearer

that makes the continuation of their interaction possible. (Habermas,

1990a, p. 58f; similarly 1984, p. 302)

In

short, the validity basis of communicative practice

resides in a tacit offer by the participants to redeem all validity

claims they raise, if asked to do so, by providing convincing grounds or "reasons."

Communicative interaction is effective so long, and only so

long, as this offer is credible. Successful communicative

interaction thus depends on an anticipation of cogent argumentation.

In fact, I would add, not only the validity but also the meaning

of a moral judgment is difficult to appreciate without grasping

a speaker's reasons. "To understand

what moral judgments and claims mean, we need to understand

how we can argue them." (Ulrich, 2010b, p. 13)

Such argumentation need not actually take place so long as the

participants can recognize each other's motives and do trust in the

readiness of the other participants to redeem their

claims explicitly if asked to do so. But implicitly, it

is at all times clear that

To

say that I ought to do something means that I have

good reasons for doing it. (Habermas, 1990a, p. 49)

Rationality

and reason-giving are inseparable, in practical-normative questions

no less than in theoretical-instrumental or other questions.

So,

what kind of good reasons might allow us to appreciate and

justify normative

claims? A

previous discussion of Strawson's (1974) analysis of the nature of moral consciousness

pointed to the kind of reasons

we need: they should help us in reestablishing the sense

of unbroken or unimpaired intersubjectivity that has been lost or is

at peril whenever normative expectations are violated (cf.

Ulrich, 2010b, p. 10f). Unresolved moral issues tend

to undermine the tacitly shared validity basis of communicative

practice. Unless a shared validity basis can

be reestablished, communicative practice risks breaking

down.

It

follows that communicative ethics depends on a model of argumentation

that can remedy a lost or impaired communicative basis. What,

then,

does cogent argumentation to that end mean? How can a shared

validity basis be reestablished in practical discourse once

it has been lost?

A communicative turn of rational ethics can succeed only to

the extent it can answer this sort of question convincingly.

The project of communicative

ethics thus amounts to the task of "recasting moral theory

in the form of an analysis of moral argumentation" (Habermas,

1990a, p. 57)

or, slightly more accurately, of reformulating Kant's moral

philosophy in the terms of a "special

theory of argumentation" (1990a, p. 44). This is where our earlier discussion of

Habermas' framework of formal pragmatics comes into play.

Discourse

ethics and formal pragmatics

Presuppositions

of moral argumentation It may be helpful at

the outset to recall some of the major ideas

that inform a formal-pragmatic approach to argumentation theory.

Basically, argumentation

theory begins where deductive logic ends: with nontrivial,

because substantial, judgments of fact or value. Justification of

such judgments reaches

beyond deductive-logical consistency

and instead raises empirical and normative questions. That is, it involves

both epistemological and practical-philosophical

validity claims – claims to the truth of knowledge (regarding

judgments

about disputed facts or instrumental relationships) and to the rightness of norms (regarding

judgments about value conflicts or interpersonal relationships).

A logic of substantial argumentation

cannot hope to establish certainty about such questions of theoretical-empirical

or practical-normative validity in a way that would be comparable to analytical

necessity; for when it comes to such questions, alternative premises

or conclusions are always conceivable. Nor can it credibly go

back today to Kant's presumption of an absolute, context-independent

philosophical viewpoint in the form of "transcendental"

philosophy. Consequently, the only manner in which

we may still hope to achieve some certainty is by

reflecting on those unavoidable presuppositions of reasoning and argumentation

that in principle would allow us to reason

and argue compellingly, even though in the practice of empirical

inquiry and moral reasoning they may not usually obtain. To

put it differently, What are the presuppositions that we cannot

help but pragmatically assume to hold in raising and discussing

empirical or normative validity

claims, regardless of the extent to which they may actually

obtain in

ordinary discursive practice? If we could identify such unavoidable presuppositions

of argumentation, we might understand them as a kind of "social-practical analogues of Kant's ideas of reason,"

as McCarthy (1994, p. 38) aptly puts it.

This

sort of presuppositional analysis (cf. Habermas, 1990a,

pp. 83-86) represents a post-Kantian,

quasi-transcendental type of reflection in the tradition of Peirce's (1878) pioneering

account of the "indefinite

community of investigators"

as an unavoidable presupposition of a pragmatic logic of inquiry. A number of authors took this

idea up prior to Habermas and applied it to the logic of theoretical

or moral justification, among them notably Royce

(1913, cited in Apel, 1972, notes 4 and 5), Mead (1934), Collingwood

(1940), Apel (1967-70, 1972, 1973, 1980, 1980a, 1981, 1987; cf. Mendieta, 2002 on the importance of this somewhat

neglected source of inspiration and collaboration for Habermas), Peters

(1974, cited in Habermas, 1993a, p. 84f), and Watt (1975,

cited in Habermas 1993a, p. 83). The basic

argument it yields in Apel and Habermas' development of Peirce's

approach on the basis of speech-act theory is that there

are argumentative presuppositions that we cannot reasonably dispute without entangling ourselves in a performative

contradiction, that is, a misfit between what we say (the

propositional content of a speech act) and what me mean to achieve

by saying it (its performative, or relational, aspect;

cf. Apel, 1987, p. 277; Habermas, 1990a, pp. 80-82, 89,

95; 1990b, p. 129; 1993b, p. 33; 1993d, p. 162). For

example, it would mean to succumb to a performative contradiction

if a speaker were to argue against some specific claim to normative validity

(performative aspect: I want to convince you of this

normative claim through my argument) by asserting that "rational argument about normative claims is not possible"

(propositional content: normative claims cannot be argued).

Much the same observation holds true, if we are to believe Apel

and Habermas, for all the conditions on which rational argumentation as such depends,

quite regardless of what it is about. There are features of

the process of argumentation that we cannot help but

assume to be respected by everyone who means to seriously participate

in an argument. As Habermas sumps up these unavoidable requirements:

The

four most important features are: (i) that nobody who

could make a relevant contribution may be excluded; (ii) that

all participants are granted an equal opportunity to make contributions;

(iii)

that all participants must mean what they say; and (iv) that

communication must be freed from external and internal coercion

so that the "yes" or "no" stances that participants

adopt on criticizable validity claims are motivated solely by

the rational force of the better reasons. (Habermas, 1998, p. 44;

cf. his similar lists in 1973c, p. 255f, and 1990a, pp.

87-89, the latter with reference to the account by Alexy,

1990, pp. 163-167, which in turn goes back to Alexy, 1978, p.

156f; for our own previous short summary, see Ulrich, 2009c,

p. 22).

Although

these requirements stand for counterfactual ideals, "every

speaker knows intuitively that an alleged argument is not a

serious one if the appropriate conditions are violated – for

example, if certain individuals are not allowed to participate,

issues or contributions are suppressed, agreement or disagreement

is manipulated by insinuations or by threat of sanctions, and

the like." (Habermas, 1993b, p. 56) The power of these

ideals is that a speaker cannot deny their relevance without

getting caught up in a performative self-contradiction. This

is what Habermas (e.g., 1973c, p. 258) means when he declares

that although being counterfactual, they are nevertheless "operative"

in any discourse. They embody a part of the general validity

basis of speech that is merely "anticipated yet effective"

(1971c, p. 140).

In

the terms of our previous introduction to formal pragmatics

(Ulrich, 2009c and d),

we are dealing with general pragmatic presuppositions of

argumentation on which we "always already" rely

as soon as we argue (cf. Habermas, 1984, pp. 25 and 34; 1998, p. 44; 2009, Vol. 2,

p. 266). Formal pragmatics, since it is able to explain

the unavoidability of these presuppositions by the means of language

analysis, speech-act theory, and argumentation theory rather

than by taking recourse to transcendental philosophy, offers itself as a framework

for elaborating contemporary concepts of rationality both in epistemology

(esp. science-theory) and practical philosophy (esp. moral theory).

Compared to transcendental

philosophy, its appeal is not only that it is more accessible

and can build on a broader basis of philosophical tools than

were available to Kant, but also that it can do so with weaker

assumptions – assumptions closer to life, as it were, as communication

and argumentation are such central features of our social lifeworld.

From

this perspective, then, we may understand discourse ethics as a

special application of presuppositional analysis. It

is an attempt to explain what kind of specific argumentative

conditions would allow justifying moral claims cogently. These conditions,

so goes the reasoning, we cannot help

but assume to be operational whenever we want to bring to bear

in communicative practice

the moral point of view, as the one viewpoint from which can decide rationally about

clashing normative claims. In

short, discourse ethics assumes the methodological function of a presuppositional

analysis of what it means to practice the moral point of view

discursively. Let us have a closer look, then.

Two

fundamental principles of discourse ethics When

Habermas introduced discourse ethics, he was exploring new theoretical

terrain. Although he was addressing theorists rather than practitioners,

he could not presuppose

that they were all familiar with the idea of a communicative turn

of ethics (which he had pioneered in close exchange with Apel,

e.g., 1972, 1980a, 1990) or even with his own formal-pragmatic

framework

of the logic of substantial argumentation (which he had developed

drawing on Toulmin's work, esp. 2003/1958). He therefore

needed to explain why a discourse-theoretical

reformulation of rational ethics made sense in the first place

and how it situated itself in the broader context of contemporary

ethical theorizing. Accordingly

his early essays on discourse ethics (esp. 1990a, b; 1993a, b, c) focus

on discussing its cognitivist, universalist,

procedural, and formal perspectives and how they relate to the

ideas of other contemporary theorists such as Baier (1958), Singer

(1961), Rawls (1971, 1985), Apel (1972, 1973,

1980, 1981, 1988), Frankena (1973), Strawson (1974),

Hare (1981), Kohlberg (1981, 1984),

MacIntyre

(1981), Mead (1934), Strawson (1974), Toulmin (1970, 1972,

2003), Tugendhat (1982, 1984, 1989), Watt

(1975), and Williams (1985); compare

Ulrich (2010a, b) for a highly selective review and discussion

aimed at preparing the present essay.

The same circumstances

may explain why Habermas, rather than explicitly and systematically deriving discourse

ethics from formal

pragmatics, chose to introduce and discuss it in terms of two distinctive principles:

the principle of

discourse ethics (D) and the principle of moral universalization

(U). This has largely remained so in his later essays (see

in particular 1993d, 1996a, 1998, 1998a; 2003a; 2009a); there

is, unfortunately, no systematic book by Habermas on discourse

ethics. I'll briefly introduce the two principles before discussing them in more detail.

The

principle of discourse ethics (D) stipulates that

(D)

Only those norms can claim to be valid that meet (or could meet)

with the approval of all affected in their capacity as participants

in a practical discourse. (Habermas, 1990a, p. 66,

similarly p. 93 and 1990c, p. 197)

and

hence, that:

(D)

Every valid norm would meet with the approval of all concerned

if they could take part in a practical discourse. (Habermas,

1990b, p. 121)

(D)

Just those action norms are valid to which all possibly affected

persons could agree as participants in rational discourses.

(Habermas, 1996a, p. 107)

(D)

Only those norms can claim validity that could meet with the

acceptance of all concerned in practical discourse. (Habermas,

1998a, p. 41)

(D)

embodies both Habermas' communicative turn of the concept

of rational justification in general and the communicative turn of rational

ethics in particular. As a specific principle of discourse ethics, the

above formulations of (D) refer to the aim of justifying norms,

that is, to questions of moral rightness. It is clear though that the underlying general principle of a discursive examination

and substantiation of validity claims is also relevant and applicable

to questions of truth and instrumental rationality, and quite

generally to all questions that lend themselves to rational

consideration of supporting assumptions and foreseeable consequences.

Habermas (e.g., 1996a, p. 107) mentions the example

of questions of democratic legitimacy; I would add questions

of legal compliance and other forms of value-rationality in

the general sense of conformity to defined values (e.g., social

and ecological standards). These different questions imply different

validity standards but not different principles of discourse;

in particular, there will be different criteria for determining

who counts as "concerned" and what kinds of "reasons"

count as relevant. In questions of truth, for example, those concerned

will be competent inquirers, and relevant reasons will refer

to high-quality observations about pertinent empirical circumstances;

whereas in questions of democratic legitimacy, those concerned

will include all citizens and relevant reasons will refer to applicable

citizens rights, legal and constitutional norms, the common

good, principles of equal treatment and minority protection,

previous democratically grounded decisions in the matter at

issue, and so on. It helps to substitute "claims" for "norms" in the above-cited formulations of

(D),

to render the

generic nature of the discursive principle obvious. The core

idea remains the same across all areas of application; it is

that discursive procedures of will-formation allow for consideration

of different perspectives and concerns, doubts and reasons,

and thus provide for a broad basis of information and legitimation.

In short, discursive will-formation is reasonable regardless

of the matter to be decided.

Although

Habermas introduces (D) as a specific principle

of discourse ethics, I therefore propose that we take it to embody the

basic procedural requirement of communicative rationality in general.

There is no reason to restrict its relevance to moral

discourse only. In the terms of formal pragmatics, (D) stands for the general pragmatic

presuppositions of valid argumentation in any kind of discourse;

these presuppositions, as we have seen, are to make sure that

all relevant contributions and concerns can be articulated and

their consideration is free from external or internal sources

of distortion. This is not to say that (D) is devoid of any ethical

concern, on the contrary; the principle may indeed be understood

to provide a basic ethical grounding of all discourses, in the

form of the cooperative stance to which we have referred above

and which sets the quest for communicative rationality off from

mere reliance on strategic rationality or non-argumentative forces. Strictly speaking

though, (D) is a discourse-ethical principle only inasmuch

as it stipulates the indispensable ethical core of all

communicative rationality, rather than in the further-reaching

sense in which Habermas

usually employs the label "discourse ethics," of a

discursive approach to moral theory.

To avoid confusion, (D)

might thus better be called a discourse-theoretical principle,

or simply a general discourse principle. Its

basic message is:

communicative rationality and communicative reciprocity go together.

It belongs to the cognitive core

not only of ethics but of all rationality that we take others'

views and concerns seriously and consider them in an unbiased

and impartial way. In this intrinsic

reference to the idea of impartiality lies the methodological

secret of formal pragmatics as it were: since impartiality

– doing justice to the perspectives of others – is both a cognitive

and a normative principle, the demands of rationality and morality

converge. That is what Habermas means, I suspect, when he seeks to

"derive" discourse ethics from the general presuppositions

of discourse rather than by normatively introducing a moral

principle.

Such

a reading of (D) suggests that it is indeed a fundamental principle

of all rational will-formation; but it also suggests that (D)

does not furnish a

sufficiently specific, constitutive principle of discourse ethics. Even

philosophers cannot have the cake and eat it – (D) is either

a general principle of reason or it is a specific principle

of moral reasoning, but not both at once. Reference to the shared ethical core of all communicative

practice does not enough to specify moral discourse, no more

than other specific kind of discourse. What

(D) fails to specify is the particular aspects of rationality

under which different types of theoretical and practical

questions need to be discussed: What does it mean to substantiate

a claim

to moral rightness as distinguished from a claim to truth, to purposive-rationality, or

to value-rationality? That is, what are the specific kinds of

"good reasons" that are required in each case? To specify the particular nature of moral discourse

and moral reasons, discourse ethics therefore needs an additional principle:

The

principle of moral universalization (U) stipulates that

(U)

For a norm to be valid, the consequences and side effects that

its general observance can be expected to have for the

satisfaction of the particular interests of each person

affected must be such that all affected can accept them

freely. (Habermas 1990b, p. 120, similarly 1990c, p. 197)

and

hence, that::

A

contested norm cannot meet with the consent of the participants

in a practical discourse unless (U) holds, that is, unless all

affected can freely accept the consequences and the side

effects that the general observance of a controversial

norm can be expected to have for the satisfaction of the interest

of each individual. (Habermas, 1990a, p. 93)

(U)

Every valid norm must satisfy the condition that the consequences

and side effects its general observance can be anticipated

to have for the satisfaction of the interests of each

could be freely accepted by all affected (and be preferred

to those of known alternative possibilities for regulation).

(Habermas, 1993b, p. 32)

(U)

A norm is valid when the foreseeable consequences and side effects

of its general observance for the interests and value-orientations

of each individual could be jointly accepted by all concerned

without coercion. (Habermas, 1998a, p. 42)

We

recognize in (U) the Kantian principle of moral universalization, discursively

redefined. Quite in a Kantian spirit, the

italicized parts of Habermas' definitions are to make sure "that

a practice of justification conducted in this manner selects

norms that are capable of commanding universal agreement – for

example, norms expressing human rights."

(Habermas, 1998a, p. 43) Unlike in Kant's formulation of

the principle, however, empirical aspects do play a certain role;

there is reference to the consequences and side-effects of norms

of action, and to the individual interests and value-orientations

of the participants. This allows moral discourses to be more

than mere exercises of abstraction and instead to take into

account the particular experiences and concerns that shape the

participants' notions of what is good and right. Therein consists

one of the basic points of a communicatively turned moral universalism:

it creates room for considering norms from the different vantage

points of participants, although with a view to giving

the moral point of view a chance.

The

purpose of (U), then, is not to enforce a "pure" Kantian

morality in communicative disguise. To be sure, moral discourse is to overcome

a merely egocentric perspective or private stance of the participants;

but that need

not mean it has to ignore their individual views and values. Discourse makes

sense in the first place because and to the extent those involved

bring in different perspectives. The aim of moral deliberation

is not to abstract from all personal motives but only to make sure

that these motives are controlled by respect and responsibility

for the concerns of others. As Habermas (1998a, p. 40) puts

it, the aim is "equal respect for everyone else

demanded by a moral universalism sensitive to difference."

This is clearly a normative consideration, one that may be

seen to reach beyond the minimal normative content of argumentation

to which (D) has already drawn our attention. Still, it

is not just a normative consideration; for taking an interest in others' interests is also an intrinsic

requirement of communicative rationality as such. (U) and (D)

are closely related in this regard – a circumstance that is

to be expected, given the ties between the moral and the rational

that we have encountered earlier. As one of Habermas' translators explains

the rationale of (U):

In

choosing to argue, each party commits itself not just to its

own rational conviction but to that of others as well. This

is the kernel of intersubjectivity in (U).… The commitment to

rational conviction must involve something like taking an interest

in others' interests. (Rehg, 1994, p. 70f)

One

may wonder indeed whether the same statement would not provide

a better description of the rationale of (D). As I see it, reference

to the kernel of intersubjectivity underspecifies the

methodological intent of (U), but it sums up the intent of (D)

rather well. Be that as it may, so much is clear: together,

(D) and (U) establish a fundamental nexus between the

two concerns of ensuring communicative rationality among those

involved on the one hand and equal respect and responsibility for all others

on the other hand

– the two major concerns to which refers the title of Habermas' (1990) first

collection

of discourse-ethical essays, Moral Consciousness

and Communicative Action. Thus seen (D) stands for the generic

intersubjective kernel of all communicative action whereas (U)

adds the specifically moral point of view that is constitutive

of moral action. While (D) takes care of the communicative

requirements of rational will-formation as such, (U) is to ensure that

the reasons a discourse identifies as good grounds

for accepting a claim are moral reasons – "good" reasons not just for

those involved but for everyone else concerned as well, in the strong

sense of being equally

good for all (Habermas, 1993d, p. 151; cf, 1990a, pp.

68-72, and 1992b, p. 248). In this "equally good for

all" consists

the justification of good reasons as moral reasons. Cogent

moral arguments refer us to reasons that deserve recognition by all, even those not

involved as participants, as they satisfy both (D) and (U).

How

do (D) and (U) relate to one another? The fact that Habermas explains

discourse ethics in terms of the two apparently similar principles (D) and (U)

has caused considerable confusion about their relationship. Many

a reader may feel a need for some additional discussion of this

rather difficult issue before moving on to a critical discussion

of discourse ethics. The present

and the next subsection are for them. Readers who at this stage

prefer to gain some critical distance before they burden themselves with more details about the

two discourse-ethical principles and how they relate

to one another, may wish to jump directly to the next main section

titled "Critical Discussion"

and then to come back to the present discussion later.

Some

text passages in Habermas' discourse-ethical writings suggest that (D) is

presupposed in (U), for instance when he refers to the communicative kernel that only

waited to be uncovered in Kant's moral principle or when he

explains

that "for the justification of moral norms, the discourse

principle takes the form of a universalization principle"

(1996a, p. 109, italics added). On other occasions he seems to

suggest that things are the other way round in that (U) is presupposed in (D), for example when he explains that "the principle

of discourse ethics (D) … already presupposes that we

can justify our choice of a norm [by means of (U)]"

(1990a, p. 66) or that "to introduce such a discourse

principle already presupposes that practical questions can be

judged impartially and decided rationally." (1996a, p. 109).

Quite frequently he also states that (U) is "derived" or "abducted" from

(D) or "operationalizes" it (e.g., 1990a, p. 82f

and 92f;

1996a, p. 109; 1998a, pp. 43 and 46).

It

is one of the innovative features of discourse ethics that it

seeks to avoid the need for "introducing" the principle

of moral universalization in ways that would boil down to a

mere appeal to the moral sense or

good will of those involved. Instead, it locates the principle

within the formal properties of practical discourse, where it

is "always already" presupposed in the form of "universal

presuppositions of argumentation" (1998a, p. 43). In

this respect it seems adequate to say that discourse ethics derives the

moral principle (U)

from the discourse principle (D) and thus does not merely postulate it

but actually justifies it. There are some difficulties involved

though. Strictly speaking, (U) is then to be considered an argumentative

(or logical) rather than a normative (moral) principle; it explains

how moral claims can be buttressed argumentatively but not why

they should, that is, why people ought to reason and

act morally. By implication,

practical discourse can be expected to produce moral insight

(i.e., moral reason) but not necessarily also the will to act

accordingly (i.e., moral motivation).

Habermas recognizes the difficulty when

he points out that "it is part of the cognitivist understanding

of morality that justified moral commands and corresponding

moral insights only have the weak motivating force of good reasons."

(1993b, p. 33) It remains unclear how discourse ethics

is to close the resulting gap between moral reason (as an

ideal of universalizing moral discourse) and moral motivation

(as a normative force that inspires and regulates moral

practice).

A

related difficulty is this. Deriving

(U) from (D) does not appear to account for the fact that the moral point of view unfolds normative force

not only in its discursive employment but also in individual

moral conscience, reflection, and action. Significantly the idea of moral universalization

as it is contained in well-known moral principles such as the

ancient Golden Rule or the categorical imperative, along with

Mead's (1934) plea for "universal role-taking" and

Baier's (1958) account of "the moral point of view,"

is much older than the idea of rationally motivated moral discourse.

But if this is so – if moral universalization was a meaningful idea long

before the communicative

turn of ethics and thus can apparently inspire moral consciousness

and conduct directly without discursive detour – it is difficult

to see how one can claim that it is grounded in discourse

rather than brought into it, say, by an act of good will

on the part of the participants. I suspect

Habermas' might respond that we indeed need to distinguish

systematically between moral universalization as an argumentative

device in discourse and as a motivating force that may very

well be effective prior to discourse and reach beyond it, for instance,

in the form of a cooperative stance that shapes "that complicated web of attitudes and feelings which

form moral life as we know it" (Strawson, 1974, p. 24,

as discussed in Ulrich, 2010b, p. 9f). As an argumentative

device, the principle of moral universalization may then be assumed

to be contained in the presuppositions of discourse

without precluding the possibility that as a motivating force,

it shapes people's individual moral consciousness quite independently of

its discursive employment.

Conversely, inasmuch as a communicative turn of ethics is already anticipated

in Kant's categorical imperative, from where it just needed

to be extracted, discourse ethics might be understood to

imply that when it comes to moral reasoning, the discourse

principle (D) is contained in (U) and thus can be

systematically derived from it rather than needing to

be "introduced" previously as a discourse-ethical

principle or by reference to the intrinsic requirements

of linguistic competence and cogent argumentation. Note that

the limitation we just considered

above – that (U) can be derived from (D)

only in its capacity as a formal principle of argumentation but not as a motivating

normative force – does not apply to the derivation of (D) from

(U); for the moral principle

can very well be understood as a normative force that motivates

an agent and still implies an orientation

towards communicative rationality.

As

a further difficulty, Habermas obviously cannot and does not intend a mutual derivation of (D) and

(U) from one another. That would amount to circular reasoning

and thus would yield a rather dubious basis for claiming that

both principles represent inescapable

presuppositions of practical discourse rather than mere conventions (cf. 1990a,

pp. 89 and 93). Even so he occasionally (e.g, 1990a, pp.

86 and 94) hints at the possibility that such a simultaneous

derivation of (D) from (U) and of (U) from (D) would not necessarily

be circular, inasmuch as the former derivation would work at the level of moral

consciousness (morality as a motivating force implies an orientation

to communicative rationality) and the second,

at the level of argumentative requirements (morality as an argumentative

force implies an orientation to moral universalization). Be

that as it may: a more credible way of grounding

discourse ethics language-analytically would consist in demonstrating

that one of the two principles is contained in the requirements

of rational discourse and the other is contained in the former

principle.

Habermas does not choose this option, however, as both principles

are equally fundamental to him; declaring either to be more

basic than the other would unavoidably cause new theoretical

problems. A one-sided derivation of (U) from (D) might

question the claim of discourse ethics to provide a genuine

development of cognitivist ethics in the tradition of Kantian

rational ethics; conversely, a one-sided derivation of (D) from

(U) might question the claim of providing a new, language-analytical

grounding of moral theory. Unfortunately though, the price to pay for avoiding these

difficulties is another difficulty: discourse

ethics remains strangely undecided, if not ambivalent, as to

how the supposed "derivation" of its two core principles

from language-analytical foundations is to be understood and

how, in consequence, the two principles relate to one another.

In

short, a certain lack of clarity does creep

in.

Some

doubts and difficulties

The above-quoted definitions of (D) and (U) are so strikingly

– and confusingly – similar that it is far from obvious that

both principles are needed and if so, what are the crucial differences

and the division of roles between them. Not surprisingly, a

lot of discussion can be found in the secondary literature about

this issue. Perhaps best known is Benhabib's

(1990) carefully argued suggestion that (U) should be altogether

discarded as in her view, it is fully implied in (D). As she sees it, the requirements

for which (D) stands, of rational argumentation and agreement,

entail

strong ethical assumptions such as equal consideration and respect

for all concerned, assumptions that amount to what she calls

"the principle of universal moral respect" (1990,

p. 337). Such a view is in line with the basic aim of discourse

ethics, of finding a new basis for moral theory in the linguistic

structure of rationally motivated communication. Inasmuch as

(D) adequately captures these linguistic presuppositions, introducing

an additional principle (U) looks at best unnecessary to Benhabib but

is more likely confusing. For example, she finds it confusing

that Habermas

tends to assign to (U) the role of argumentatively guaranteeing

consensus on moral validity claims; for doing so risks

turning our attention away from the procedural focus of

(D), by which discourse ethics means to replace the earlier

substantial focus of rational ethics. As she

argues:

Consent

alone can never be a criterion of anything, neither of truth

nor of moral validity; rather, it is always the rationality

of the procedure for attaining agreement which is of philosophical

interest. We must interpret consent not as an end-goal but as

a process.… It is not the result of the process of moral

judgment alone that counts

but the process [as such]. Consent is a misleading

term for capturing [this] core idea behind communicative ethics.…

(Benhabib, 1990, p. 345)

As

a second concern, Benhabib fears that (U)'s formulation is prone

to misinterpretation. Rather

than elucidating the procedural focus of discourse ethics as

it applies specifically to moral judgment, it may open up the door to utilitarian reasoning

and thereby might have us regress behind the level of Kant's moral

reasoning:

Habermas

has given "U" such a consequentialist formulation

that his theory is now subject to the kinds of arguments that

deontological rights theorists have always successfully brought

against utilitarians. Without some stronger constraints about

how we are to interpret "U," we run the risk of regressing

behind the achievements of Kant's moral philosophy. (Benhabib,

1990, p. 343)

As Benhabib

concludes:

I

want to suggest that (U) is really redundant in Habermas' theory

and that it adds little but consequentialist confusion to the

basic premise of discourse ethics. (D) [as the expression

of this premise]

states that only those norms can claim to be valid that meet

(or could meet) with the approval of all concerned in their

capacity as participants in a practical discourse. (D), together

with [the] rules of argument [that it entails] and the normative

content [that] I summarized as the principles

of universal respect and egalitarian reciprocity, are in my

view quite adequate to serve as the only universalizability test.

(Benhabib,

1990, p. 344)

And

hence,

It is my

claim that this core intuition, together with an interpretation

of the normative constraints of argument in light of the principles

of universal respect and egalitarian reciprocity, are sufficient

to accomplish what (U) was intended to accomplish, but only

at the price of consequentialist confusion. (Benhabib,

1990, p. 345)

At

first glance, Benhabib's argument seems to blur the fine line between the two notions of morality

that we considered above, as a normative force and as an argumentative

device. At a closer look, however, this

defect is probably one of formulation rather than substance.

Substantially, the circumstance that Habermas finds it

necessary to qualify (U) as an argumentative rather than normative principle

may be seen to strengthen Benhabib's case;

for if (U) is a merely or at least mainly argumentative principle, one may indeed ask why it still

needs to be stipulated (or "derived") as a separate

principle rather than simply being considered an integral part

of the presuppositions of rational argumentation according to

(D). One might even take Benhabib's doubts further and support it with

the following observation. Should it turn out that unlike what

Benhabib suggests, moral universalization entails some methodological requirements

that

are not contained in (D), including possibly the need for some

source of normative force that reaches beyond the general ethical

core of a communicative stance, then (U) would indeed amount to an

indispensable addition to (D); in which case some serious doubts about the success of