Werner Ulrich's Home Page: Ulrich's Bimonthly

Formerly "Picture of the Month"

November-December

2012

CST's Two Ways:

A Concise Account of Critical Systems Thinking

Introductory note. This is a prepublication version of an article written for the third edition of the Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science, edited by Saul I. Gass and Michael C. Fu, to be published by Springer New York in June, 2013 (Gass and Fu, 2013). The final version of the article was accepted for publication in the Encyclopedia on November 3, 2011. As the publication of the Encyclopedia is experiencing some delay (it should originally have been published in May, 2012), I have decided to prepare this prepublication version.

Due to its format of an encyclopedia entry, this article differs a bit from the content and style of my usual Bimonthly essays. Rather than exploring mainly new territory, it reviews established but not always accurate views on what critical systems thinking (CST) is and how its two current main strands, as represented by the work of my British colleagues on total systems intervention (TSI) or "creative holism" on the one hand and my work on critical systems heuristics (CSH) or "boundary critique" on the other hand, relate to one another. Conforming to the requirements of an encyclopedic work, the article seeks to provide a neutral, fair, and accurate account of both strands, giving equal weight to different notions of CST regardless of the extent to which I share them. To facilitate comparison, it presents the two strands of CST in a strictly parallel manner, using the same structure and the same criteria. In short, it aims to offer a concise and rigorous, non-partisan account of CST's two ways.

Despite the focus on informing readers about current ideas rather than exploring new ones, there are two novel aspects. First, to my knowledge a comparative, concise and non-partisan account of this kind has not been available thus far. It should thus come as good news to those readers who have been looking in vain for such an overall account of CST. And second, the comparative approach leads to a finding that does in fact open up some new territory. Counter to the established wisdom, according to which the two strands of CST represent largely incompatible notions of "critical" professional practice, it turns out that they share a central concern: both aim to support professionals in dealing systematically with the "bigger picture" of the problem contexts or situations in which they are expected to provide competent advice. To this end, both frameworks focus on the contextual assumptions on which all professional intervention and advice depends. Either approach does this in a new and specific way; both do it systematically; neither replaces the other. I have found this theme of developing the contextual sophistication of professionals so important that meanwhile, I have dedicated to it a further-reaching theoretical contribution (see Ulrich, 2012a, b).

Suggested

citation: Ulrich, W. (2013). Critical systems thinking. In S.I.

Gass, and M.C. Fu (eds.), Encyclopedia of Operations Research and

Management Science, 3rd edition, 2 vols., New York: Springer,

Vol. 1, pp. 314-326. Prepublication

version: CST's two ways: A concise account of critical systems thinking. Ulrich's Bimonthly, November-December 2012,

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2012.html.

|

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

Introduction: systems thinking about good practice

Critical systems thinking (CST) is a development of systems thinking that aims to support good practice of all forms of applied systems thinking and professional intervention. In its simplest definition, CST is applied systems thinking in the service of good practice. Three essential ideas are that:

- Professional practice in all its stages and activities, from the formulation of problems to the implementation of solutions and the evaluation of outcomes, involves choices that need to be made transparent and require systematic examination and validation.

- Systems thinking, although it does not protect against the need for such choices, at least offers a methodological basis for examining them systematically.

- Consequently, applied systems thinking should make it standard practice to employ not only a hard (quantitative, scientific) and/or a soft (qualitative, interpretive) but always also a systematically critical (reflective, questioning) perspective and mode of analysis.

Taking these three elements together, CST not only recognizes that all applied systems thinking involves choices in need of critical reflection but also draws on systems thinking itself as a source of systematic critical reflection and deliberation.

CST and OR. Critical systems thinking has essential roots in operations research and management science (OR/MS), along with some equally important roots in philosophy, social theory, and other disciplines. It has applications in OR/MS as well as in many other professional fields that it is increasingly influencing; among them are environmental planning and management, public policy analysis, information systems design, social planning, evaluation research, technology assessment and risk regulation, and others. Unlike most of these fields, OR/MS was from the outset conceived as applied systems thinking: its systems perspective was to distinguish it from conventional notions of applied science and professional intervention. Critical systems thinking may be understood as an expansion of that original idea. CST's focus is on the fundamental theoretical and normative assumptions that inform the formulation and analysis of problems within their contexts, rather than on the more technical aspects of model building, analysis, and validation, or on procedural aspects of project management and consensus formation.

Two main sources of CST within OR/MS. Critical systems thinking developed from the confluence of two largely independent strands of thought about OR practice. The first strand originated in the 1970s at the University of California at Berkeley and can be regarded as a development of, and response to, Churchman's (1968, 1971, and 1979) philosophy of social systems design, which itself was a development of his earlier pioneering work on OR/MS (Churchman, Ackoff, and Arnoff, 1957). The second strand originated in the 1980s at the University of Hull in England and can be regarded as a response to the development, in British OR, of soft systems methodology (Checkland, 1981, 1985; Checkland and Scholes, 1990), along with a number of soft OR methods or problem structuring methods (Rosenhead, 1989) and some other approaches to complex and dynamic problem contexts (e.g., management cybernetics and viable systems diagnosis, Beer, 1972, 1985), all of which not only led to a growing variety of methods and underlying research paradigms but also to a perception of paradigmatic insecurity or crisis in parts of the OR profession.

Two key issues of critical systems thinking. CST responded to these developments in American and British OR/MS by focusing its methodological efforts on two key issues:

- The first issue emerged from recognizing that the way professionals understand and define problem contexts has value implications, in the practical sense that it may do more or less justice to the different views and needs of people. Professional practice cannot avoid, in every specific context of intervention, choices as to what views (observations, data) and what needs (concerns, interests) of people are to be considered relevant and what other views and needs should not or cannot be considered equally relevant. The question is: “What should constitute the basis of knowledge and values for rational practice?” When it comes to this normative core of practice, there is a need to support professionals and everyone else concerned in handling their assumptions in a transparent and self-critical way, as well as to deal adequately with the consequences these assumptions may have for the different parties concerned.

- The second issue emerged from recognizing that different problem situations put different demands on professional competence and accordingly also on the methods professionals use. Professional practice cannot avoid, in defining and employing its methods of analysis and intervention, assumptions about the nature of problem situations, particularly with respect to the kind of complexity that matters; for real-world complexity takes different forms and there is consequently no single best way to understand and handle it. The question is: “What are the assumptions, strengths and weaknesses of different approaches and methods regarding the nature of problem contexts, that is, different kinds of social reality?" When it comes to the variety of methodological options available today in applied systems thinking, there is a need to support professionals in handling these options in a theoretically informed and justifiable way.

Critical systems thinking, then, is the use of systems ideas for probing into these two different (though not entirely independent) sources of contextual selectivity, that is, assumptions that shape the understanding and handling of problem contexts – the selection of relevant facts and values, and the selection of adequate methodologies and methods. Both shape the way problems will be understood within their contexts. However, they place rather different demands on good practice. What assumptions different systems approaches make regarding the nature and complexity of problem contexts depends on their theoretical underpinnings and thus can be identified theoretically once and for all; good practice in this respect means informed methodology choice. By contrast, relevant facts and values need to be identified anew in each specific problem situation and therefore are mainly a responsibility of practice itself; good practice in this respect means reflective practice.

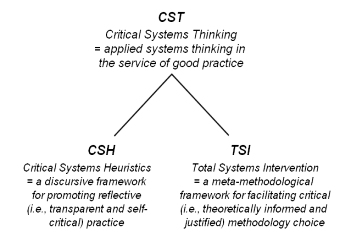

Two different strands of critical systems thinking have accordingly developed: critical systems heuristics (CSH) and total systems intervention (TSI). Their shared core idea is that systems thinking can be a useful source of critical reflection about contextual selectivity. A precise yet comprehensive definition of CST may therefore be formulated as follows.

Definition: Critical systems thinking (CST) is an application of systems thinking that aims to support good practice with regard to (a) the normative core of the knowledge and value basis that informs professional findings and conclusions and (b) the theoretical assumptions that inform the variety of methodologies and methods employed. The common denominator of (a) and (b) is that they both condition the perception of relevant problem contexts.

Terminology: CST, CSH, and TSI. The term "critical systems thinking" was coined in July 1989, when the originators of the two strands met at the 33rd Annual Conference of the International Society for the Systems Sciences (ISSS) in Edinburgh, Scotland, and decided to unite their efforts under the umbrella of critical systems thinking. Due to differing methodological conceptions and philosophical backgrounds, the cooperation between the two strands of CST remained a brief episode in the late 1980s and early 1990s; but the term CST has survived as a name for their shared interest in handling contextual assumptions critically.

Some confusion was subsequently caused by the circumstance that both strands have continued to refer to their efforts as critical systems thinking. For the sake of terminological clarity, it is advisable to use the term as a higher-level concept under which CSH and TSI may meaningfully be subsumed, rather than identifying it with either strand (see Fig. 1).

Fig.

1: Critical systems thinking (CST) and its two strands – basic

terminology

(Source: adapted from Ulrich, 2003, p. 327)

|

November 2012 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

December 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Due to their separate development and also to different theoretical foundations, the two strands, despite their shared core idea and complementary ends, have brought forth partly incompatible frameworks for CST. They are therefore introduced separately. However, to facilitate comparison and synthesis, the account follows the same structure and uses the same criteria.

Critical systems heuristics (CSH): facing the normative core of professional practice

CSH was fully worked out in the late 1970s at the University of California at Berkeley but became widely known only in the early 1980s, when the main theoretical work (Ulrich, 1983) was published with some delay after the author's return to Switzerland. With a view to submitting his work to the test of practice, Ulrich assumed a position as chief policy analyst and evaluation researcher in the public sector and also returned to teaching at his home university, the University of Fribourg (Philosophical Faculty). This double experience in public policy making and university teaching has helped Ulrich to develop CSH continuously since. CSH has meanwhile found resonance and applications in many applied disciplines and is gradually evolving into a more comprehensive framework for reflective practice in the civil society (Ulrich, 2000), critical pragmatism (Ulrich, 2006 and 2007), and philosophy for professionals (Ulrich, 2007).

Core idea. Professional practice involves validity claims (e.g., to truth, rightness, sincerity, objectivity, rationality, and relevance) that have practical consequences but which it cannot fully justify. Applied systems thinking makes no exception, for its effort to appreciate the systemic nature of problems and thus, to gain a comprehensive or whole-systems view of problem situations, does not supersede the need for making value judgments as to what exactly is to be considered the problem to be dealt with (i.e., what merits improvement); what constitutes the relevant problem context (i.e., what is the sum-total of the relevant facts and concerns); and wherein would consist a good solution (i.e., how to define improvement). No kind of systems methodology or other methodology can fully justify the answers to such inevitable questions as “Whose problem is to be solved in the first place?” and “For whom should improvement be achieved and for whom not?” What is possible, however, is a conscious and careful handling of this normative core of all professional intervention.

Critical systems thinking as understood in CSH therefore begins with the idea that holistic or whole-systems thinking – the quest for comprehensiveness – is a meaningful effort but not a meaningful claim. Doing full and equal justice to the views and values of all the people concerned is an ideal; but applied systems thinking should not be expected to achieve ideals. To put it differently, holism is not a philosophically and methodologically credible source of justification, it is a problem. Hence, rather than trying to be holistic, CSH tries to support practice – professionals as well as ordinary citizens – in appreciating the inevitable selectivity of the claims involved (e.g., to putting a problem well and to securing improvement) with regard to the facts (observations) and values (concerns) it takes to be relevant and on which its rationality and consequences depend.

In practical contexts of action, selectivity usually translates into partiality, in the sense that different parties will be affected differently. CSH consequently also aims to help professionals and citizens in analyzing these consequences and how they may change if assumptions about relevant observations and concerns are modified. Good practice cannot avoid selectivity and partiality, but it will make it transparent to all those concerned how the selectivity of assumptions and the partiality of consequences depend on one another. It will give all the parties an opportunity to articulate their critique, and will then try to modify assumptions and consequences accordingly. Critical systems thinking, thus understood, is reflective practice – a methodologically disciplined effort to support such processes of critique systematically.

Methodological approach. CSH is both a new philosophical foundation and a practical implementation of a discursive framework for value clarification and critique. Like the previously used concept of the normative core of rational practice, the term "value clarification" again refers to the selectivity of both considerations of facts (the empirical or knowledge basis of rational action) and of values (the normative or value basis of rational action) in contexts of practical action. The choice of the knowledge basis of professional interventions – of relevant data, judgments of fact, personal views, and other empirical conjectures (e.g., anticipated consequences of action) – has no less normative implications than has the choice of its value basis, that is, of relevant concerns, notions of improvement, and ethical standards. Both sources of selectivity and partiality demand a critical handling.

But applied systems thinking not only implies empirical and normative selectivity, it also holds a key to handling such selectivity critically. Systems thinking compels professionals, as well as everyone else concerned, to pay attention to the systems boundaries that delimit any specific system of interest. Systems thinking can thus be understood as a tool for reflecting about the boundaries of concern that (consciously or not) inform all analysis of problems and related proposals and arguments, regardless of whether systems terms are used in the first place or others. Systems thinking then becomes a source of critique – of questioning boundary assumptions and the ways they condition validity claims – rather than, as it is more usually understood, a source of justification, that is, a way of buttressing validity claims by more comprehensive considerations of fact and value.

In the terms of CSH, critical systems thinking can support professionals and all the parties concerned in identifying and questioning boundary judgments that delimit the reference systems for defining problems and relevant contexts, solution designs, evaluations, proposals for action, and so on. Boundary judgments determine for a number of basic boundary issues and related boundary categories what is to be considered and what is to be left out when it comes to defining relevant observations (judgments of fact) and concerns (judgments of value). A reference system is the set of boundary judgments that together define the context of application to which a specific claim or proposal refers and for which it is valid.

Boundary judgments are the perfect device for questioning the relevance and quality of reference systems; for unlike what one might assume at first glance, they define not just the scope of the context considered (i.e., how narrow or comprehensive it is delimitated) but equally its content, that is, what observations about that context are collected and taken to be relevant, how they are formulated, interpreted and used, what importance is attached to them and how well related conjectures are argued. This is so because any aspects of a problem situation that are not properly considered, say, because those involved argue incoherently or anticipate consequences incorrectly, or fail to do justice to the concerns of others, have in fact been excluded from the relevant knowledge and value basis. Even if one recognizes some aspects as relevant and agrees with others they should be considered but then fails to take them properly into account, due to lacking knowledge, to an error of judgment or some communicative misunderstanding, or because those in control of the situation decide to suppress their discussion, these aspects have in fact (deliberately or not) been excluded from the considered reference system. Thus the argumentative quality of a validity claim or related discussion very well reflects itself in boundary judgments.

The main device to promote such argumentative quality is critical systems discourse, a dialogical form of boundary critique. Boundary critique is basically a systematic process of identifying the boundary judgments that are built into any specific validity claims, in an effort to unfold their normative core (selectivity) and what it may mean for the parties concerned (partiality). A second basic aim is to show that there are always options for defining boundary judgments, and to make it visible how different the claims in question may look in the light of such options. In cooperative settings where the parties are prepared to try and see whether they can agree on their boundary judgments, these can then be modified accordingly. In controversial settings this may not be possible; boundary critique then gains a new meaning and consists in employing boundary judgments for critical purposes against those who are not prepared to disclose and question them or who even try to impose them on the basis of authority and power rather than argumentation. Critical systems discourse thus becomes a discursive process of challenging validity claims by demonstrating that and how they depend on boundary judgments that have not been declared or are imposed by non-argumentative means.

To be sure, selectivity, not comprehensiveness, is the fate of everyone who tries to solve problems and to do something about the state of the world. The point of boundary critique consists, in the terms of CSH, in a critical turn of applied systems thinking and its notion of good professional practice. It recognizes that there is no objective but only a critical solution to the fundamental problem of practical reason, of how claims to rational practice can be justified in the face of their inevitable selectivity and partiality. The problem has remained unresolved in practical philosophy, the philosophical discipline concerned with the normative dimension of rational action, in that no theoretical solutions have been found that would at the same time be practicable (a more complete account of the concept of a critical solution is given in Ulrich, 1983, 2001, and 2003).

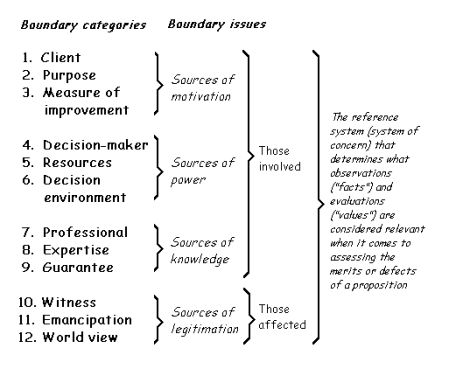

Methodological core principle. CSH's answer to the unresolved problem of practical reason is the principle of boundary critique. It says that both the meaning and the validity of claims depend on the reference system to which these claims refer, and hence, that one cannot understand and qualify (appreciate and criticize) their adequacy without examining the boundary judgments that define that reference system. The basic idea and aim of CSH, then, is to support systematic processes of boundary critique as a way to secure at least a critical solution of the problem of practical reason. To this end, there are 12 CSH boundary categories (see Fig. 2).

Fig.

2: Boundary categories of critical systems heuristics

(Source:

Ulrich, 1983, p. 258)

These boundary categories stand for four crucial sources of selectivity built into all practice. Each boundary category translates into two boundary questions, one asking what is the case (“is” mapping, i.e., descriptive analysis) and the other what should be the case (“ought” mapping, i.e., normative analysis). This yields an extensive checklist of boundary questions that explicitly define the precise intent of each boundary category (Ulrich, 1987, 1996, 2000; Ulrich and Reynolds, 2010). They can be used, first, to identify boundary judgments systematically; second, to examine how alternative boundary judgments may change the way one sees problem definitions, findings, and conclusions, and thus what is considered to be adequate and rational; and third, to challenge any claims to knowledge, rationality or improvement that rely on hidden boundary judgments or take them for granted.

The last-mentioned application leads to an argumentative employment of boundary judgments, known as polemical or emancipatory boundary critique, that creates an improved symmetry of critical competence among all the parties concerned, professionals and citizens alike, regardless of their theoretical knowledge or special expertise with respect to the problem at issue. As a practicable model of cogent critical argumentation (Ulrich, 1983, 1993, 2000), it embodies a critical pragmatization of Habermas’ (1973, 1979) ideal model of rational practical discourse (a model that underpins his discourse ethics and confines it to being a moral theory rather than a practicable model of moral justification). It constitutes a chief methodological backing of the critical turn of the concept of rational practice proposed above.

In sum, CSH can be defined as a methodological framework for boundary critique, that is, for identifying and debating boundary judgments, with the aim of securing at least a critical solution to the unsolved problem of practical reason – the question of how claims to rational practice can be justified despite the unavoidable selectivity and partiality of all practice. Despite its emancipatory implications (the aspect for which it is best known), CSH should not be misunderstood and used as an emancipatory systems approach only; its principle of systematic boundary critique is vital for sound professional practice in general, whatever importance may be attached to emancipatory issues. For the same reason, CSH does not aim to be a self-contained systems methodology, but is better understood as an approach that should inform all critical professional practice, whatever specific methodology is used.

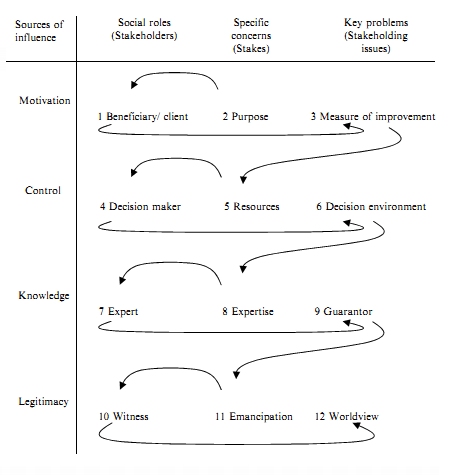

Practical implementation (main procedure): Boundary critique is best implemented as an iterative process of reflecting on, and discussing, the implications of alternative boundary judgments. When some boundary judgment changes, the reference system of which it is constitutive will change, too; consequently, all other boundary judgments may need being reconsidered and adapted. However, iterative processes are not particularly easy to learn and to handle; experience with boundary critique suggests that it is useful for beginners to have available, and follow, a standard sequence for unfolding the boundary categories and questions of CSH (see Fig. 3).

Fig.

3: CSH's process of unfolding – a standard sequence of boundary

critique

(Source: Ulrich and Reynolds, 2010, p. 259; adapted

from Reynolds, 2007, p. 106)

Total systems intervention (TSI) or creative holism (CH): ensuring informed methodology choice

TSI stems from work done at the University of Hull, England, in the mid and late 1980s, about the evolution of OR and systems thinking in terms of changing underlying theoretical assumptions. This work resulted in the early 1990s in the proposal of a meta-methodology for choosing among methodologies according to situational requirements (Flood and Jackson, 1991; Jackson, 1991). By that time CSH and TSI had joined their efforts under the new name of “critical systems thinking” (CST), after previously using different names such as critical systems approach (CSH) and critical management science (TSI); but due to differing notions of what critical practice was to mean, the two strands of CST ultimately found it difficult to integrate their approaches and consequently returned to developing their frameworks separately. Both have nevertheless continued to use the name critical systems thinking. Meanwhile, Jackson (2003, 2006b) refers to his work on critical systems thinking and practice as creative holism (CH).

Core idea. Applied systems thinking depends for its choice of systems methodologies and methods on basic assumptions regarding the nature of the problem contexts (typically: organizational contexts) with which it is dealing. Some of these assumptions can usefully be captured in terms of a number of sociological paradigms for describing the nature of social reality as they have been analyzed, for example, by Burrell and Morgan (1979), as well as by organizational images or systems metaphors as they have been described most systematically by Morgan (1986). Different systems methodologies, because they usually are developed with different problem contexts in mind, can similarly be characterized in terms of underlying metaphors and paradigms. Hence, since the characteristics of both problem contexts and systems methodologies can be captured in terms of adequate paradigms and metaphors, it becomes possible to match contexts and methodologies in a systematic way and thus to support professionals in choosing among the increasing number of available systems methodologies and conforming methods those best suited to deal with a problem situation at hand.

CST as understood in TSI/CH therefore begins with the idea that systems thinking – the attempt to understand organizational or societal problem contexts in systems terms – is meaningful only to the extent people are aware of the sociological paradigms and organizational metaphors that inform it. Since different systems methodologies rely on different paradigms and metaphors – that is, on different theoretical assumptions about the nature of problem contexts – applied systems thinking depends for its justification and rationality on paradigmatic fit between systems methodologies and problem contexts.

In applied OR/MS, as in other forms of applied research, the requirement of paradigmatic fit translates into a need for informing the selection and use of methodologies and methods by previous paradigm analysis as well as, where relevant, metaphor analysis, as a condition for doing justice to the nature of the problem context at issue. TSI/CH consequently puts its critical focus on the theoretical underpinnings of alternative research paradigms rather than, as does CSH, on the normative core of professional practice. CST, thus understood, is about methodology choice – a theoretically informed way to support processes of matching methodologies and methods with problem contexts.

Methodological approach. The basic strategy of TSI/CH can be described as a contingency approach to methodology choice, based on paradigm analysis and, to a lesser degree, also on metaphor analysis of the three major traditions of systems thinking thus far – hard, soft, and critical systems thinking. The idea is that there is no such thing as a best systems methodology and underpinning tradition of systems thinking; rather, situational aspects of the problem context at hand determine what tradition of systems thinking is best suited as a source of methodological guidance and specific methods or tools of intervention. In OR/MS such an approach promises to resolve the OR in crisis debate of the 1970s and 1980s; for it allows hard and soft OR approaches to be seen as appropriate for dealing with different problem contexts rather than competing for the same ones.

Contingency frameworks are also called contingency theories, as they involve theoretical generalizations about the crucial aspects of the application domain to which the framework is to be applied. This theoretical device is often used in the social sciences (e.g., in management and organization theories) when a variety of approaches is required to handle a given class of problems, as the proper approach is dependent (contingent) on the situation or, more precisely, on a range of changing situations.

Applied to contexts of professional intervention, using a contingency approach implies that some independent (contextual) variables can be identified empirically which regularly, for reasons that can be explained theoretically, may be expected to condition the outcome of interventions. A contingency approach can then (and only then) make sure that the way one deals with a situation matches situational requirements, and on that basis can also justify the credibility of the results. To the extent this condition is fulfilled, one can properly speak of a contingency theory. It follows that the crucial question for any contingency approach is whether it can identify and theoretically justify a small number of empirical dimensions (ideally only two) in terms of which the range of situations in question can be usefully classified, so that each type of empirical situation can then be identified in a relevant and reliable way.

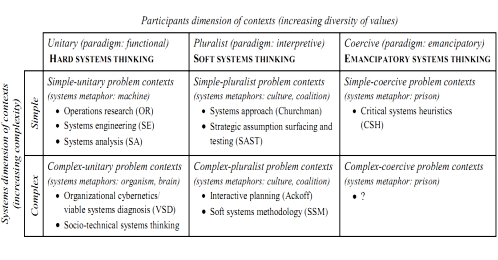

Methodological core principle. TSI/CH’s answer to the problem of ensuring paradigmatic fit between intervention approaches and problem contexts is a classification of problem contexts, and of systems methodologies assigned to them, called the system of systems methodologies (SOSM). It says that systems methodologies and conforming methods are well chosen if their underlying systems metaphor (machine, organism, etc.) and/or paradigm (functionalist, interpretive, etc.) match with the nature of the problem context, or more exactly, with assumptions about the kind of complexity that needs to be handled in the problem context. The basic idea and aim of TSI/CH, then, is to support systematic processes of informed methodology choice, as a way to secure paradigmatic fit between intervention methods and intervention contexts. To this end, TSI/CH proposes the SOSM (see Fig. 4).

Fig.

4: The extended system of systems methodologies (SOSM)

(Source:

adapted from Flood and Jackson, 1991, p. 42;

Jackson, 1991,

pp. 29 and 31; 2000, p. 359)

(Click on the figure to enlarge it)

There was an earlier, four-celled version of the SOSM (Jackson and Keys, 1984) that is now often cited as the origin of the TSI strand of CST. However, it only distinguished hard and soft methodologies and its discussion in that early paper did not yet introduce the notion of critical systems thinking.

CSH became known to Jackson and Keys shortly after publishing their 1984 paper. First hints at a planned extension of their work appeared in a few articles in the late 1980s (Jackson, 1987, 1990); the extended SOSM was presented later in Flood and Jackson (1991) and Jackson (1991).

Due to the underlying logic of the SOSM, the extended scheme could not manage to include CSH except by constricting its notion of critical systems thinking considerably. This logic assumes that any methodology can be meaningfully assigned to a single type of problem context and to a conforming (dominant) theoretical paradigm. There is no room in such a scheme for an approach that focuses on the genuinely normative core of practice as such, whatever the theoretical paradigm adopted may be and the choice of methodology and conforming methods it may inspire. This makes it understandable why the extended SOSM rather arbitrarily assigned CSH a merely emancipatory purpose, as opposed to the critical purpose of the SOSM. To render this choice more plausible, CSH was associated with a prison metaphor, which then seemed to render CSH adequate for coercive problem contexts only and thus provided a rationale for assigning it to a specific emancipatory paradigm (for critical discussion and alternatives, see Ulrich, 2003). In this way, CSH became in the SOSM scheme an apparently self-contained methodology that, quite against its original intentions, was to be chosen (or not) as an alternative to soft and hard systems methodologies. Its concern for the practical-normative side of all practice thus moved out of sight.

In British OR/MS, CSH was henceforth understood mainly through the lens of the SOSM, and critical systems thinking became widely identified with TSI. Consequently, CST was now almost the same as the SOSM – an updated contingency framework for methodology choice, as well as for continuing discussions about the evolution of OR/MS (e.g., Jackson, 2006a). Both uses attracted much interest and the mentioned difficulties of the extended SOSM did not hamper its success in helping to raise awareness in the profession that there are options for conceiving of good professional practice. The discussion that the SOSM was able to generate has helped to make CSH more known, so that its core principle of boundary critique is increasingly being recognized as an important, independent source of critical thought on practice. These diverse successes of the SOSM certainly have contributed to the comparatively high level of methodological awareness and discussion by which the OR/MS profession distinguishes itself from other fields, which in turn has allowed it to pioneer soft and critical systems ideas that are now radiating into many other fields.

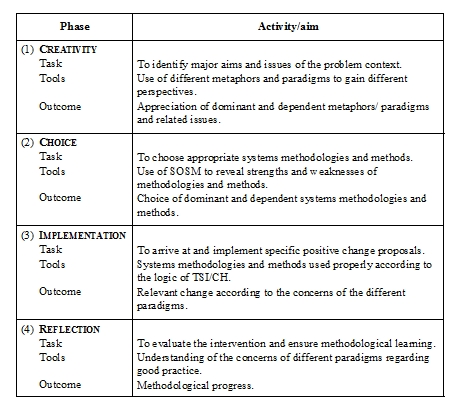

Practical implementation (main procedure). To support methodology choice in practice, the SOSM still needed to be embedded in a methodology properly speaking, that is, a framework that would guide practitioners in asking relevant questions and proceeding systematically. This is what total systems intervention (TSI), a name adopted in 1991, is all about. It stands for the practical procedure of methodology choice and implementation that Flood and Jackson (1991) proposed on the basis of the SOSM. The aim is to provide a meta-methodology for methodology choice and implementation. The procedure may be employed in a linear or iterative way. Originally it consisted of three phases labeled creativity, choice, and implementation, to which Jackson (2003, 2006b) later, in the extended version that he now prefers to call creative holism, added a fourth phase, “Reflection” (see Table 1).

Table

1: The meta-methodology of TSI/CH:

standard phases of methodology choice and

use

(Source: adapted from Flood and Jackson, 1991, p. 54;

Jackson, 1991, p. 276;

2000, p. 372; and 2006b, p. 654)

Legend: TSI = total systems intervention =

phases 1-3;

CH = creative holism = phases 1-4; SOSM = system of systems methodologies

The creativity phase is intended to encourage consideration of what alternative systems paradigms and root metaphors might mean for thinking about a problem context at hand, so that a dominant metaphor can be identified as most adequate, that is, in effect, preference can be given to either a hard (functionalist) or a soft (interpretive) or critical (emancipatory) orientation.

In the choice and implementation phases, a conforming particular systems methodology should then be chosen based on the SOSM and used to implement specific change proposals.

Finally, a new element in CH as compared to its predecessor TSI is the reflection phase, which brings in an element of reflective practice as CSH understands it, by looking at the outcomes of methodology choice and implementation rather than at its theoretical justification only. Although the underlying notion of evaluation is still not genuinely practical in the sense of CSH and practical philosophy, this development does promise to open up new chances for reflective practice.

Another new element, following a considerable amount of discussion in the literature about methodological complementarism or pluralism (Jackson, 1997, 1999), mixing methods (Midgley, 1997), and multi-methodology (Mingers and Gill, 1997), is that creative holism, unlike TSI, no longer insists on choosing a single dominant paradigm. Instead, a combination of methodologies, or parts of methodologies and conforming methods, is now encouraged, which makes the framework more flexible and brings it closer to actual practice. As Jackson describes it, CH now is a “meta-methodological” framework that aims to help practitioners to “harness the various systems methodologies, methods and models” by being “multi-paradigm, multi-methodology and multi-method in orientation” (Jackson, 2006b, pp. 248 and 253).

A Summary Comparison of CSH and TSI

To provide an overview of the discussed aspects of critical systems thinking, Table 2 summarizes the accounts of CSH and TSI in a way that should facilitate comparison.

Table 2: CSH and TSI compared

|

Aspect |

CSH |

TSI / CH |

|

Core idea |

Professional practice involves validity claims that cannot be justified theoretically but at least can be handled openly and critically in the process of intervention itself. |

Professional practice involves methodological choices that can be justified theoretically by analyzing underpinning research paradigms and systems metaphors. |

|

Critical focus |

Reflective practice: surfacing the reference systems underpinning all judgments of fact and value, and analyzing how they condition practical claims (e.g., problem definitions, relevant contexts, standards of improvement, and proposals for action). |

Paradigm analysis: surfacing the theoretical underpinnings of alternative research paradigms (e.g., functionalist, interpretive, emancipatory, or post-modern) and analyzing how they condition different perceptions of problem contexts and suitable methodological choices. |

|

Approach |

Critical systems discourse: a discursive framework for value clarification and critique. |

Contingency theory: a contingency framework for methodology choice and use. |

|

Methodological core principle |

Boundary critique: unfolding the selectivity of reference systems. |

Informed methodology choice: matching systems methodologies with problem contexts. |

|

Main critical device |

Checklist of boundary questions: a definition of boundary categories for “is” and “ought” mapping (i.e., descriptive and normative analysis) of reference systems. |

System of systems methodologies (SOSM): a classification of problem contexts and conforming systems methodologies. |

|

Implementation |

A discursive process of unfolding selectivity: a standard sequence of boundary critique. |

A holistic meta-methodology of paradigm analysis: standard phases of methodology choice and reflection. |

Legend: CSH =

critical systems heuristics;

TSI/CH = total systems intervention/creative

holism

Conclusion: the essence of critical systems thinking

The claim of professional practice to relevance, rigor, and rationality depends on many requirements. Among these, two crucial ones are putting the problem well and tackling it by means of adequate methods. In different ways, they both embody crucial requirements of professional competence. They both stand for efforts to make sure that relevant issues are properly identified and the implications of related assumptions are made transparent and evaluated.

- Putting problems well is an issue that involves empirical (observational) as well as normative (ethical) problem structuring and reflection. The selection of relevant facts and values depends on a proper understanding of the problem, which is hardly achievable without questioning the scope and diversity of the social context that matters. It also depends on the extent to which justice is done in practice to the diversity of views and concerns of the different parties concerned. A problem may be ill-defined so long as this normative core of any quest for rational practice is not well understood.

- Choosing and employing methods properly involves analysis and reflection about the demands of problem situations on the one hand and about the availability of methods that respond to these demands on the other. The selection of adequate methodologies and methods depends on a proper understanding of the theoretical and paradigmatic assumptions involved, which is hardly achievable without questioning the nature of the complexity that matters. It also depends on the extent to which the matching of such assumptions with specific situations is successful in practice. A methodology and conforming methods may be ill-chosen so long as this theoretical core of the quest for rational practice is not well understood.

Neither effort replaces or precludes the other. Critical systems thinking, properly understood, aims to promote good practice with regard to both. To this end, the two strands of CST bring to bear within the field of OR/MS, and in the applied sciences in general, new philosophical and theoretical foundations, along with new practical tools for analyzing contextual complexity and diversity. CSH draws on practical philosophy and consequently conceives of rational practice in terms of discursive tools of value clarification and critique, in particular boundary critique and discourse. TSI/CH draws on organizational sociology and conceives of rational practice in terms of theoretically informed tools of methodology choice, in particular paradigm analysis and metaphor analysis.

Different as the resulting frameworks of CSH and TSI are, their shared concern remains the idea that good professional practice depends crucially on making sure that problems are well put and methods of intervention are well chosen; and that to meet both requirements, it is essential to properly situate problems in their contexts and make sure one understands those contexts well. Formulated in everyday terms, the essential message of CST to professionals might thus be summarized as follows:

Critical Systems Thinking: Its Operational Imperative

As a professional intervening in a specific context, pay attention to your contextual assumptions and try to identify and examine them systematically, so as to understand them well.

Then make sure everyone concerned understands them well, too. How do they shape the facts and values people consider relevant?

Work towards mutual understanding about how problem definitions and solutions depend on and change with the facts and values considered relevant. Make sure divergent views and values are properly addressed.

Adapt your choice of methodologies and methods to the amount of diversity that you find in the problem context, and to the resulting nature of the complexity that matters.

Whatever problem definitions and methods your professional practice ultimately relies on, reflect on the validity claims your professional findings and conclusions imply and how, if taken as a basis for action, they may affect the different parties concerned.

Make boundary critique a standard practice to this end, and always remember that no professional intervention can do justice to all views and values, that is, can justify all its implications.

And finally, deal with this inevitable lack of complete justification in a transparent and self-reflecting way. This is what critical professional practice is all about.

(Note: The third sentence of this "Operational Imperative" and its layout in seven paragraphs have been added here to its original layout in the Encyclopedia article.)

Also see the following entries to the Encyclopedia: Community operations research; Cybernetics and complex adaptive systems; Practice of operations research and management science; Problem structuring methods; Soft systems methodology; Systems analysis; Systems dynamics.

References for the original Encyclopedia entry

Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. Penguin Press. Harmondsworth, UK (2nd ed. Chichester, UK: Wiley, 1981).

Beer, S. (1985). Diagnosing the System for Organizations. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Burrell, G., and Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. London: Heinemann.

Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley,

Checkland, P. (1985). From optimizing to learning: a development of systems thinking for the 1990s. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 36, No. 9, pp. 757-767.

Checkland, P., and Scholes, J. (1990). Soft Systems Methodology in Action. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Churchman, C.W. (1968). The Systems Approach. New York: Dell Publishing.

Churchman, C.W. (1971). The Design of Inquiring Systems: Basic Concepts of Systems and Organization. New York: Basic Books.

Churchman, C.W. (1979). The Systems Approach and Its Enemies. New York: Basic Books.

Churchman, C.W., Ackoff, R.L., and Arnoff, E.L. (1957). Introduction to Operations Research. New York: Wiley, and London: Chapman & Hall.

Flood, R.L., and Jackson, M.C. (1991). Creative Problem Solving: Total Systems Intervention. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Habermas, J. (1973). Wahrheitstheorien. In H. Fahrenbach (ed.), Wirklichkeit und Reflexion: Walter Schulz zum 60. Geburtstag, Pfullingen, Germany: Neske, pp. 211-265.

Habermas, J. (1979). What is universal pragmatics? In J. Habermas, Communication and the Evolution of Society, Boston, MA: Beacon Press, pp. 1-68.

Jackson, M.C. (1987). New directions in management science. In M.C. Jackson and P. Keys (eds.), New Directions in Management Science, Aldershot, UK: Gower, pp. 133-164.

Jackson, M.C. (1990). Beyond a system of systems methodologies. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 41, No. 8, 657-668.

Jackson, M.C. (1991). Systems Methodology for the Management Sciences. New York: Plenum.

Jackson, M.C. (1997). Pluralism in systems thinking and practice. In J. Mingers and A. Gill (eds.), Multimethodology : The Theory and Practice of Integrating Management Science Methodologies, Chichester, UK: Wiley, pp. 347-378.

Jackson, M.C. (1999). Towards coherent pluralism in management science. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 50, No. 1, pp. 12-22.

Jackson, M.C. (2000). Systems Approaches to Management. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

Jackson, M.C. (2003). Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Jackson, M.C. (2006a). Beyond problem structuring methods: reinventing the future of OR/MS. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 57, No. 7, pp. 868-878.

Jackson, M.C. (2006b). Creative holism: a critical systems approach to complex problem situations. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 23, No. 5, pp. 647-657.

Jackson, M.C., and Keys, P. (1984). Towards a system of system methodologies. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 35, No. 6, pp. 473-486.

Midgley, G. (1997). Mixing methods: developing systemic intervention. In J. Mingers and A. Gill (eds.), Multimethodology : The Theory and Practice of Integrating Management Science Methodologies, Chichester, UK: Wiley, pp. 249-290.

Mingers, J., and Gill, A. (eds.) (1997). Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice of Integrating Management Science Methodologies. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Morgan, G. (1986). Images of Organization. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage (3rd ed. 2006).

Reynolds, M. (2007). Evaluation based on critical systems heuristics. In B. Williams and I. Imam (eds.), Systems Concepts in Evaluation: An Expert Anthology, Edge Press, Point Reyes, CA, pp. 101-122.

Rosenhead, J. (ed.) (1989). Rational Analysis for a Problematic World: Problem Structuring Methods for Complexity, Uncertainty and Conflict. Chichester, UK: Wiley (rev. ed: Rational Analysis for a Problematic World Revisited: Problem Structuring Methods for Complexity, Uncertainty and Conflict, J. Rosenhead and J. Mingers, eds., 2001).

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland: Haupt (paperback reprint ed., Chichester, UK: Wiley, 1994).

Ulrich, W. (1987). Critical heuristics of social systems design. European Journal of Operational Research, 31, No. 3, pp. 276-283.

Ulrich, W. (1993). Some difficulties of ecological thinking, considered from a critical systems perspective: a plea for critical holism. Systems Practice, 6, No. 6, pp. 583-611.

Ulrich, W. (1996). A Primer to Critical Systems Heuristics for Action Researchers. Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull.

Ulrich, W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

Ulrich, W. (2001). The quest for competence in systemic research and practice. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 18, No. 1, 2001, pp. 3-28.

Ulrich, W. (2003). Beyond methodology choice: critical systems thinking as critically systemic discourse. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 54, No. 4, pp. 325-342.

Ulrich, W. (2006). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics. In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business Ethics, Vol. I, Oxford, UK, and Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang Academic Publishers, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich, W. (2007). Philosophy for professionals: towards critical pragmatism. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 58, No. 8, pp. 1109-1113.

Ulrich, W., and Reynolds, M. (2010). Critical systems heuristics. In M. Reynolds and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A Practical Guide, London: Springer, in association with The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, pp. 243-292.

Additional references for the Preliminary note:

Gass, S.I., and Fu, M.C. (eds.) (2013), Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science, 3rd edition. New York: Springer.

Ulrich, W. (2012a). Operational research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective. Part 1: OR as applied systems thinking. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 63, No. 9, pp. 1228-1247. Previously published as advance online publication, 14 December 2011.

Ulrich, W. (2012b). Operational research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective. Part 2: OR as argumentative practice. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 63, No. 9 (September), pp. 1307-1322. Previously published as advance online publication, 14 December 2011.

Suggested citation of the present prepublication article:

Ulrich, W (2013). Critical systems thinking. In S.I.

Gass and M.C. Fu (eds.), Encyclopedia of Operations Research and

Management Science, 3rd edition, New York: Springer. Prepublication

version: CST's two ways: a concise account of critical systems thinking.

Ulrich's Bimonthly, November-December 2012,

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2012.html.

Picture data Digital photograph taken near Bern on 3 November 2007 around 6:30 p.m. ISO 100, exposure mode program, aperture f/5.6, exposure time 1/80 seconds, exposure bias -0.3; focal length 14 mm (equivalent to 28 mm with a conventional 35 mm camera), metering mode center-weighted average, contrast normal, saturation high, sharpness normal. Original resolution 3648 x 2736 pixels; current resolution 700 x 500 pixels, compressed to 194 KB.

November-December, 2012

|

A careful look at two ways of critical systems thinking (CST) |

„How

can critical systems thinking support professionals?”

In

two different but complementary ways, says this essay.

Notepad for capturing personal thoughts »

|

Personal notes:

Write

down your thoughts before

you forget them! |

|

Last

updated 22 Jun 2014 (title layout), 1 Nov 2012 (text);

first published 1 Nov 2012

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2012.html