|

|

|

Tools

for critical

contextualization They

say that travel broadens the mind. But, as the English essayist

and novelist G.K. Chesterton (1921) observed, you must

have the mind. That is, one has to be prepared to

see and appreciate what one encounters while traveling. Just

as important, one should be prepared to see what looks different upon returning home. As every

experienced traveler knows, the adventure of traveling is also

one of coming home: it is then that we realize the difference

it makes. For a short time at least, before routine takes over

once again, we may see our familiar habits and surroundings

in a new light. The familiar and obvious has become a little

less obvious. If one is open to that experience,

it offers an opportunity for appreciating accustomed ways of

thinking or acting in deeper ways than before, and thus perhaps

also for questioning and developing them.

This

is just what I hope that my readers will experience with the

present series of essays. It has led us into a land of ideas

that for most of us who do not happen to be scholars of Indology

has been and will remain rather unfamiliar – ancient India's tradition of Vedanta philosophy, particularly as we find

it in the Upanishads. However, one does not need to

"have the mind" of an Indologist to return home from

this excursion with open eyes. As we are about to return

to our more familiar, "Western" (and in my personal

case, Kantian) tradition of thought,

let us try and see what the excursion may add to

our understanding of the proper use of ideas in inquiry and

practice. Ideas are general, whereas practice is always situational;

how can competent practice bring together the situational and the general

in meaningful ways? This is the central question that has accompanied

us through this series of essays. The way we have framed it

has been in terms of a need for critical contextualization

of all claims to knowledge, rationality, and improvement.29)

Four

basic themes and corresponding tools I suggest we organize the concluding two essays, beginning with

this one, around four basic

themes that have emerged with a view to supporting

this need. They relate to four essential issues in the use of general

ideas: (1) the need for unfolding the meaning of general

ideas in particular contexts of application; (2) the normative

implications of any contextualization of ideas and the consequent

need

for moral reflection; (3) the proper use of ideas

in argumentation; and (4) the pragmatic need for supporting the critically-contextual

use of ideas by operational forms of practical discourse.

These

four themes in turn will have us consider four related heuristics,

that is, conceptual tools for critically-contextualist thought,

to which I will refer as (1) the "spectrum idea,"

a basic tool of meaning clarification in Upanishadic reflection

and discourse; (2) "the moral idea

in context," a critically-contextualist extension and

pragmatization of the Kantian principle of moral

universalization that is inspired by the spectrum idea; (3) the logic of "suppositional

reasoning," a reflective practice of thinking and acting

as if; and (4), "boundary discourse,"

a discursive implementation of critical contextualization in

contexts of applied inquiry and decision-making. Table 4 gives

an overview.

|

Table 4: Critical

contextualization of general ideas:

four basic

themes and corresponding heuristics

|

|

Four

key issues

|

Four

essential themes

|

Four

basic heuristics

|

|

Meaning

clarification: Unfolding the situational meaning

of general ideas

|

Upanishadic

discourse:

Managing the tension between "this"

and "that"

|

Spectrum

idea :

A double movement of critically contextual

thought

|

|

Normative

testing:

The normative implications of contextualized

general ideas

|

Moral

idea in context:

Contextualizing the principle

of moral universalization

|

Enlarged

thought:

A shorthand formula for contextualized

moral thought

|

|

Suppositional

reasoning:

The argumentative use of general

ideas

|

Extrapolative

license:

Towards a discursive logic of substantial

inference

|

The

logic of "as if":

The critical

turn of suppositional reasoning

|

|

Implementation:

Securing critically contextual practice

|

Critically

contextual reflection:

A discursive operationalization

|

Boundary

discourse:

The critical turn of the rational,

the moral, and the general

|

|

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich

|

Heuristics

for critical contextualization (1):

The "spectrum idea,"

or how to practice Upanishadic discourse

Practical

reasoning, whether in the forms of applied inquiry and professional

intervention or of everyday problem solving and decision-making,

takes place in specific

contexts of application or, as I will say for the sake of brevity,

in "situations." The practical is situational. The value of general ideas, but also their

difficulty, is that they take us beyond the

immediate concerns that we associate with situations. They create

distance. This helps us to see the presuppositions

and limitations of our situational concerns and claims. Remember

that in order to see one's own standpoint, it is necessary to first take

a step back.

The

art of "standpoint

spotting," as we called it in Part 3, has much to

do with the skill – and discipline – of gaining and maintaining

distance to our own views and concerns. The "spectrum idea"

can guide this process of standpoint spotting. It is a tool

for shifting our standpoint systematically within a range of

divergent or complementary perspectives.

Like

any tool, this one has its limitations, too, and I would

like to make them clear from the outset. Basically, when

it comes to applying general ideas to particular situations,

we face the two questions of their situational

meaning on the one hand and their situational validity on

the other hand. Although the two issues are closely interdependent,

they

face us with different methodological requirements – clarification

of meaning on the one hand, validation of claims on the other

hand. My proposed use of the spectrum idea applies mainly to the first

question. The spectrum idea is not a tool for validating claims

but at best for assessing and questioning them.

The question of meaning asks

what a general idea "means" in the specific situation

at hand: What is its intent

as applied to this particular situation; what does it tell us about proper

ways to see and handle the situation? In the methodological

terms used earlier (in Part 3), we need some

heuristics

that can help us to

"approximate" the intent of a general idea, so as to understand

what difference we want the idea in question to make in

our perception and handling of the situation.

Once we are clear

about this basic task of meaning clarification, another task

poses itself, concerning the question of validity:

How valid is this understanding; or, inasmuch as people may

disagree, how can we rationally assess and justify it? Methodologically

speaking, what types of argument allow us to justify

the practical implications of general ideas in specific situations,

or at least to deal

critically with these implications?

Of

the four themes and corresponding heuristics proposed in Table 4,

the first

two focus on the issue of meaning clarification. They are the

topic of the present essay.

The other

two, which will be in the center of the next and final essay

of the series, focus on the issue of argumentative validation

and will thus lead us back to the question that motivated this

series of exploratory essays, the question of what role we should

assign to the moral idea (along with other general ideas) in

assessing and arguing moral claims.

Contextualization

tool

# 1: the spectrum idea We first introduced

the spectrum idea in Part 3 with reference to Prince (1970)

as a notion that can help us in pragmatizing the ideal character

of general ideas (see Ulrich, 2014b, esp. pp. 4-10 and 32-37). It is, as we said with Kant, a tool for

"approximating"

the situational meaning of general ideas. Meanwhile we have

come to understand both Kant's pure concepts of reason (such

as, in particular, the moral idea) and the Upanishadic ideas

of ancient Indian thought (in particular, the notions of atman

and brahman) as limiting concepts or endpoints of thought,

as we also have called them, towards which we can orient our thought, although we

can never claim to do full justice to them.30)

The spectrum idea

offers itself particularly when we face pairs of opposing reference

points for thinking through an issue, say, when a particular

perspective of the issue is challenged by the ideal intent

of a relevant general idea. For example, in the case of the moral idea, two

opposing limiting concepts might refer to a specific group of people for whom we find

ourselves responsible at one end of the spectrum, and to the notion of

a global moral community at the other end. Critical thought can

then move in-between these limiting concepts and explore

the range of options available for at least partly doing

justice to both of them.

The

basic spectrum graph The

spectrum idea is about opening

up and thinking through a range of options for clarifying the

situational meaning of a general idea, that is, for contextualizing the

idea in a critically reflective manner. In Part 3 (Fig. 2)

I tried to capture this notion with a simple graph that I still

find helpful and which I reproduce here for the reader's convenience.

(The particular) "The

context I see" (The

general)

<-¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦->

Copyleft  2014 W. Ulrich

2014 W. Ulrich Fig. 2 (repeated): The spectrum idea

Conceiving of the universe of conceivable standpoints for seeing

an issue

in terms of a continuum of more or less particular

vs. universal perspectives

(Source: reproduced

from Part 3, see Ulrich, 2014b, p. 32,

Fig. 2)

The

graph stands for the notion that our thoughts and actions – the ways people see things and search to improve them – are always an expression

of situational views for which there are

options. We can think of these options as different standpoints in the

spectrum. Accordingly, relevant standpoints and conforming contextual

assumptions may be identified

by moving both left and right in the spectrum, that is,

by iteratively emphasizing mainly particular considerations

of fact or value – selected circumstances or concerns that matter "to

us" or to some well-delimited target group (or "client

group") "here and now" – versus placing greater

emphasis on more general considerations that matter to

people other than those immediately interested or to served,

elsewhere and/or in future.

As a rule, the context assumed

in a statement of fact or value, or in a proposal for action,

will represent a mixture of the two pure types of focus that

would consist either in considering

aspects of immediate interest to those involved or served only

(a purely self-serving

stance)

or, alternatively, in trying to do justice to everyone and everything (a

purely

altruistic stance). In-between these two "pure" options

lies a more pragmatic range of options for defining the

relevant context. For example, one might try to include in the

situation of concern not everyone but at least those people who,

although they are not involved, are likely to be affected or

concerned in some more than marginal ways. Moving from such

a middle position a bit towards the left one might try to narrow the group of

people concerned to those who can get involved within reasonable constraints

of time and resources, and/or to those whose concerns can be

identified in other feasible ways. Alternatively, moving

to the right, one might include previously unconsidered concerns

(or ways of being affected) in the definition of the group of people concerned, and/or place

more weight on impacts to

people who cannot get involved within reasonable constraints

of time and resources, including children, future generations,

and non-human life.

Further, the contexts people see

as relevant will be

shaped by varying degrees of personal "realism" and

"idealism," that is, orientations mainly towards the empirical

and "feasible" (what can be done about a situation

in

the light of the "facts and figures" people see) or towards the desirable and "good

and right" (what should be done in the light of people's notions of improvement and worldviews).

And so on. A number of further variations of perspective could

easily be outlined along these lines; in the final essay of

the series I'll suggest one

such variation in the form of the professional tool of "boundary critique," which focuses

on a systematic way to identify the normative implications of

interventions into situations, or related proposals and claims.

In

essence, the idea is to appreciate situations in the light of

varying combinations of particular

(or individual, subjective, private) and general (or universal,

objective, public) considerations of fact or value, so that

any specific definition of "the" situation of concern

may be understood as one of many conceivable positions

in the spectrum. A "spectrum" is a continuum of such

positions (or standpoints, perspectives). To

adapt the basic graph to our present discussion, we may add the "situational"

element as follows:

(The particular) "The

context I see" (The

general)

<-¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦->

(The

situational)

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich Fig. 2 (adapted): Basic situational

spectrum

Conceiving

of the situational as a confluence of the particular and the

general

(adapted from Fig. 2, in Ulrich, 2014b, p. 32)

A

short notation At

times I find it practical to use a shorthand notation for this

kind of spectrum idea, for example, to take quick notes during

a conversation or to mark a passage in a text for

later consideration, as follows:

(C)

<---|---|---|-->

(U)

or

shorter

<---|---|---|-->

or

C <–> U

or

even just

<--->

The

latter

two forms are particularly useful for taking notes

in the margins of books or papers.

(C) and (U) symbolize a contextualizing and a universalizing

perspective, respectively, and the left and right arrows

remind

us that contextual reflection always calls for an iterative change

of perspective or, as we described it in Part 3, for a

"double movement of thought."31)

.

Applied

to moral reasoning, we might think of "particular" (contextualizing)

and "general" (universalizing) orientations of thought as standing for a primarily

self-centered, interested versus a more altruistic,

disinterested perspective, respectively. The resulting "context

I see" will be more or less selective as to the

facts and values considered

relevant, and corresponding notions of improvement will

be more or less responsive to different concerns. A basic

situational spectrum for moral reasoning may thus be construed

as a double movement of thought between the two ideal-types

of "partial" and "impartial" judgment.

As a second example, in dealing with ecological issues we might

want to think of the two endpoints in terms of "unsustainable"

vs. "sustainable" policies, or of "local action"

and "global thought," and so on. The important thing

is that we interpret the spectrum idea so that it captures a crucial tension that,

if managed carefully, can be conducive to productive contextual reflection

and debate.

An

Upanishadic extension of the spectrum idea In principle, the idea of a situational

spectrum lends itself to capturing any divergent perspectives

that may help us understand a context that matters. From an

Upanishadic perspective we

might, for example, explore the idea of contextual reflection in terms of

the logic of "this"

and "that" (i.e., the empirical and the

ideational worlds or domains of knowledge) or, in the more analytical

terms of Part 4, in terms of first- and second-order knowledge.

Accordingly we might then see the basic situational spectrum as follows

(see Fig. 7):

"This" "The

context I see" "That"

<-¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦->

(First-order

knowledge) (Second-order

knowledge)

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich Fig. 7: Basic this-and-that spectrum

Conceiving of a relevant context in terms of

the Upanishadic logic

of "this"

and "that"

(simple version, not recommended)

This

modified spectrum can certainly inspire meaningful reflection;

but the more important reason why I single it out here is that

it allows me to articulate a caveat. Tempting as it

may be to conceive of the tension of "this" and "that" in

such a way, as representing the two extremes of a spectrum,

it is also potentially misleading and for this

reason I do not recommend it. While

Fig. 7 adequately captures the idea that whatever view

of a situation we adopt, it will represent some combination of

"this" and "that" world (i.e., it will "realize" varying

degrees of either), it risks leading

us astray with respect to the proper place of "this"

and "that" in Upanishadic thought. Based

on our earlier account in Parts 4-6, I would argue

that a genuinely Upanishadic perspective will place the "this" (the

realm of first-order knowledge) in the middle rather than at

the left end of the spectrum, so as to associate it with "the context I see." That is,

it will associate the "this" with an individual's or group's current universe of discourse,

the universe within which people move at any specific moment. By

contrast, it will associate

the "that" (the realm of second-order knowledge) with

the two endpoints of the spectrum represented by the Upanishadic core ideas of atman and brahman

(Fig. 8):

("That") ("This") ("That")

Atman "The

context I see" Brahman

<-¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦-----¦->

Ideal:

self-knowledge Ideal:

universal

knowledge

(Atmavidya) (Brahmavidya)

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich Fig. 8: Refined this-and-that spectrum,

or

atman-brahman spectrum

Conceiving of a relevant context in terms of a double quest

for knowing oneself and

for considering the

total relevant universe

(recommended version of the this-and-that

spectrum)

Fig. 8

represents a more genuine understanding, I would argue, since

to Upanishadic

thought, atman and brahman are the only proper embodiments

of the realm of the "that" (i.e., of "higher"

or second-order knowledge, para vidya), whereas the realm

of the "this" is represented by the phenomenal world

of our less-than-ideal, forever fragmentary and unstable knowledge

of experience, (i.e., "lower" or first-order knowledge,

apara vidya); compare the earlier discussion in Part 4

(see Ulrich, 2015a, p. 6). Accordingly, only these two embodiments

of the "that" can serve as limiting concepts properly

speaking, that is, as endpoints of thought towards which we can orient

our situational reflection but which will always remain beyond what we

can claim to achieve. By contrast, the realm of the "this"

refers to the multiple and partial contexts

people see and refer to in dealing with situations of concern

to them. It represents what Müller (1879, p. xxxii) described

as a merely "temporary reflex" of that other, full reality

that no-one can credibly claim to grasp as such. We can always do better though, by

examining our views and concerns (the "this") in the

light of general ideas (the "that") and then revising

them (both the "this" and the "that") accordingly, and so forth – the

double movement of thought that we associate with the spectrum

idea (see Part 3, Ulrich, 2014b, pp. 29-37).

It

is, then, a close next step to also assign its proper place

in the this-that spectrum to the third

Upanishadic key concept that we analyzed in detail, jagat (see

Parts 5 and 6, Ulrich, 2015b and c). I suggest

it embodies the middle ground of the spectrum, the realm of

the "this," from which we can and need to gain distance

by moving towards atmavidya on the one hand and brahmavidya

on the other hand. Fig. 9 depicts the resulting concept

of Upanishadic discourse.

"That"

universe

within "This"

self-authored universe "That"

universe without

(Second-order

discourse) (First-order

discourse) (Second-order

discourse)

Atman <--------------------------- Jagat

------------------------->

Brahman

(The

Self / individual) (This

world of mine/ours) (The

whole / universe)

(The particular) "Realizing"

one's universe of discourse (The

general)

Ideal: deep subjectivity Ideal:

pragmatic excellence Ideal:

enlarged thought

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich Fig. 9: Upanishadic discourse:

Jagat

moving between atman and brahman

A spectrum of discourse universes represented by the two limiting

concepts of atman (the

universe within) and brahman (the universe without).

Moving back and forth between them allows us to better understand

jagat, our self-authored universe of discourse, and the

way it shapes and limits our views and concerns

Towards

jagatvidya Understood

along the lines of Fig. 9, the concept of jagat brings

in a pragmatic twist to Upanishadic discourse. It then offers

itself as a counterbalancing force against the potential overpowerment

and paralysis of thought and action caused by the idealizing

demands of atmavidya and brahmavidya,

along with the unavailability of an operational stopping rule for second-order

discourse (i.e., it never reaches a natural and definitive end). But

what is a fitting ideal for this pragmatic twist? I am not

aware that an ideal such as jagatvidya would have been formulated

in the Upanishadic literature. If indeed such an ideal has not

been described,

it might have to be invented and would

then perhaps come close to an Upanishadic equivalent of the

idée fixe

of my current work, the aim of working towards a framework of critical

pragmatism for reflective practice

(e.g., Ulrich, 2006b, c, and 2016).

It

is worthwhile to briefly pause and envision such an ideal of

jagatvidya. I associate it with a conception of reflective pragmatism in

which Upanishadic and Kantian thought would join forces. For Kant (1787, B828; cf. the discussion

in Ulrich, 2006b, p. 58f), practical reason is "pragmatic"

when it is not "pure," that is, does not remain in

the realm a priori concepts of reason but applies

to the world of experience and action, including research and

professional practice. In corresponding Upanishadic language,

we may say that thought is pragmatic when it does not remain in the realm of

the "that" but relates its quest for atmavidya

and brahmavidya to the world of the "this,"

that is, to effective action in the jagats within which

we move and try

to improve our daily lives. This is not fundamentally different

from Kant's call upon mature agents to act according to the

ideas of pure reason (e.g., the ideas of free will and

morality) and thus to "realize" in the realm of practical

reason what theoretical reason has no power to achieve in its

domain of competence, reason's acting according to its own principles

or laws. In harmony with this call to action, Kant (1786, B109;

1787, B835f, cf. B385f; 1788, A115f) posits practical reason

as the stronger of the two expressions of reason: while theoretical

reason has to obey the laws of nature, practical reason can

autonomously establish its own principles and can thus breathe life

into general ideas of reason through the thoughtful and

responsible actions of mature agents.

Upanishadic

and Kantian reflection thus meet in a shared concern for finding

a middle ground between the ideal and the real; a middle ground

motivated by a search for pragmatic excellence. In

Upanishadic terms, jagatvidya would call upon practical men and

women not only to question their ways of acting in the light

of a double quest for "realizing" atman and

brahman, but also to make sure that these reflective

efforts lead to effective action. Jagatvidya would in

this sense mediate Upanishadic reflection with a (some will say: Western) pragmatic orientation.

More precisely, pragmatic excellence aims at a reflecting kind of "pragmatic performance" (J. Dash, 2011) that would

be informed by critical distance to itself, as it were, thanks

to its twofold quest for atmavidya and brahmavidya

– or, speaking with Kant, for self-reflection and enlarged

thought –

though without losing sight of the imperative of effective action.

Such critical distance is achieved by systematically

unfolding the tension of the "this" and the "that";

of first- and second-order discourse; of the particular and

the general; of situational (contextual) and general (universal) concerns of practical

engagement, and so on; in short:

<---|---|---|-->

The result is an integrated,

Upanishadic-Kantian notion of critical pragmatism. It aims to facilitate a systematic process of contextual reflection

by means of two interdependent and complementary movements of

critical thought, a process that can benefit from Upanishadic

ideas but which also lends itself to support our Kantian notion of "approximating" the content of general

ideas of reason:

The first movement, symbolized

in Upanishadic thought by the quest for realizing brahman, is a movement towards

decontextualization, that is, towards freeing our understanding

of situations from insufficiently reflected contextual

premises. Such premises often embody an "I/we" and

"here and now"

perspective that prevents people from engaging with the views

and concerns of others and seeing the big picture, that is,

from engaging in what Kant (1793, B157f, cf. Ulrich, 2009b,

p. 10) intended with "enlarged thought" or what in more

contemporary terms is also meant by "interconnected

thought" (Vester, 2007, cf. Ulrich, 2015d).32)

The second

movement, symbolized by the

quest for realizing atman, is a movement towards (re-)

contextualization, that is, towards enhancing whatever general understanding

of an issue we may have (the big picture) with an effort

to gain a deeper understanding of the specific perceptions,

needs, and concerns

of the people involved or affected, as factors

that condition their views of it. Appropriate contemporary ideals

are "deep subjectivity" (Pole, 1972) and "mindfulness"

(Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

We thus have an iterative process of decontextualizing

and (re-) contextualizing issues as shown in Fig. 10.

Decontextualizing thrust - - - - - - - - ->

"That"

universe

within "This"

self-authored universe "That"

universe without

<<

Idealizing orientation | Idealizing

orientation >>

Atmavidya <----------------- Jagatvidya

---------------> Brahmavidya

Pragmatizing

orientation >> | <<

Pragmatizing orientation

(Deep

subjectivity) A

particular "realization" of the world (Enlarged

thought)

in an

unfolding universe of

discourse

allowing for pragmatic excellence

<- - - - - - - - -

(Re-) Contextualizing thrust

Copyleft  2016 W. Ulrich

2016 W. Ulrich |

Fig. 10: Three discursive orientations

Upanishadic

discourse as a process of "realizing"

one's self-authored universe of discourse through a

double movement of thought that iteratively contextualizes and

decontextualizes an issue or claim under consideration,

so as to achieve adequate degrees of atmavidya (self-reflection),

jagatvidya (pragmatic situational performance), and brahmavidya

(enlarged thought)

Upanishadic

discourse It may be useful at this stage,

before moving on, to briefly recapitulate the emerging

concept of Upanishadic

discourse (or, more precisely, of Upanishadic-Kantian

discourse) that informs our heuristic tool # 1. The essential

idea is a discursive process of critical contextualization.

To this end, the concepts of atman, jagat, and brahman

are understood to refer to three different universes of discourse

that as a rule shape "the context I/we see" and thus

can serve as complementary sources (or reference points) of

contextual

reflection and discourse. It may help readers to think of them

as being roughly parallel not only to Kant's three key ideas

for reflecting on the human condition – the "psychological"

idea of Man (or soul), the "cosmological" idea of

the World (or universe), and the "theological" idea

of God (or the notion of an absolute totality of conditions;

see the discussion in Part 2, Ulrich, 2014a, esp. pp. 8-12, as

summed up

in Table 3 on p. 12) – but also, and even more strikingly, to the contemporary

linguistic model of "three

worlds" in terms of which different linguistic expressions

or "speech acts" (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1969) can be analyzed. A prominent example

is provided by Habermas' version of speech-act theory (1979, pp. 53-68,

and 1984, pp. 309 and 329; cf. Ulrich, 2009c, pp. 9-12);

he explains the "expressive," "regulative," and "constative" functions

of speech by the way speech acts alternatively, or often also

simultaneousy, refer to "my" subjective world of inner

experience, to "our" social world of interpersonal

relations, and to "the" outer world of external nature,

respectively. From an Upanishadic perspective, the three worlds together

describe a spectrum of useful, complementary perspectives for unfolding the contextual assumptions

that inform speech acts in the form of personal intentions

and emotions (expressive function of speech acts), interpersonal

values (regulative function), and situational or external

facts taken to be relevant (constative function). Further,

an

Upanishadic perspective adds to this notion the three corresponding,

reflective ideals of atmavidya, jagatvidya, and brahmavidya

or, as I suggest we translate them into contemporary "Western"

language: deep subjectivity, pragmatic excellence, and enlarged

(or interconnected) thought.

An

important methodological point to keep in mind is that such

an Upanishadic-Kantian concept of discourse should help us understand the endpoints

of the spectrum

as limiting concepts towards which, guided by the two

ideals of atmavidya

and brahmavidya, we can orient systematic efforts of

proper contextualization and decontextualization. At the same

time, this concept of discourse is to help us pragmatize the

process of contextual reflection, in that it encourages us to

associate the concept of jagat

– or dynamically speaking, of jagatyam

jagat (i.e., jagat unfolding in a universe of forever changing

jagats) – with a pragmatic middle

ground in-between the two endpoints, that is, a set of

less-than-ideal contextual assumptions within which the quest for pragmatic excellence moves.

The corresponding

new ideal is jagatvidya, the art and discipline of unfolding

the contextual presuppositions at work in all human claims to

meaningful speech, valid knowledge, and rational action.

Just like atmavidya and brahmavidya entail a reflective stance

that for critical purposes abstracts from current contextual

presuppositions and at times may also bring in an idealizing

orientation, jagatvidya may be understood to entail a pragmatizing

orientation towards "pragmatic performance" (the concept

borrowed earlier from J. Dash, 2011) or, as I would translate

it using Kant's term, towards adequate "approximation"

of pragmatic excellence based on an effort of critical contextualization.

The

three vertical bars

in our shorthand notation for such contextual reflection thus

gain a more specific meaning, beyond simply indicating movement

of thought: they can be understood to refer to three

ideal-typical universes

of discourse symbolized by atman, jagat, and brahman, and to the corresponding reflective

ideals (or critical perspectives) of deep subjectivity (atmavidya), pragmatic excellence

(jagatvidya), and enlarged thought (brahmavidya).

Their shared concern is a systematic quest for contextual

awareness or mindfulness. Motto:

"Deep subjectivity,

pragmatic excellence, and enlarged thought:

three Upanishadic

ideas for critical contextualization"

Together the

three perspectives describe

an enhanced understanding of the

basic tension that we have identified throughout this series

of essays as a core methodological

difficulty in applying general ideas to particular situations, I

mean of course the tension between the two divergent but interdependent perspectives

of (C) and (U).33)

The

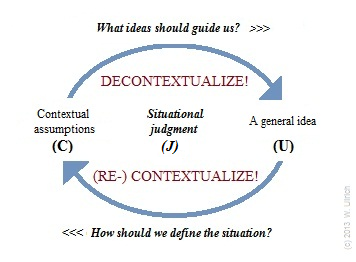

cycle of critical contextualization, adapted Neither

of the three reflective ideals is good enough to allow the process

of situational judgment to come to an end. As the basic imperative

of maintaining the tension reminds us, the iteration

of contextualization and decontextualization must go on:

whatever understanding of an issue or

a situation we have reached, we should take care to remain aware of its limitations,

that is, its inevitable failure to do justice to each

and all of the three ideals. Proper pragmatization must face this difficulty and

try to handle it in transparent and clear ways – the aim

of critical pragmatism. In general terms, using the shorthand

notation introduced above, we can state this requirement as

follows:

J

= f (C, U)

Whether

we are aware of it or not, situational judgment (J) is a function of how

we both contextualize

(C) and universalize (U) an issue. From an Upanishadic perspective,

the symbol (J) in this formula may also be read as referring

to jagat, the limited and unstable universe of thought

and action within which any quest for pragmatic performance

takes place, and the related requirement of jagatvidya,

the effort of making this universe clear to ourselves and

to all others concerned.

Earlier,

in Part 3 of this series of essays, I first suggested a

graphic depiction of the basic idea of a cycle of critical contextualization (see

Ulrich, 2014b, p. 37, Fig. 4); the following graph adapts it so as to make the

meaning of the above formula clear, and with it the place we

give to general

ideas in situational judgment (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11: Situational judgment

Situational

judgment – understanding a jagat – brings together contextual

assumptions with one or more general ideas; it involves both a contextualizing

and a decontextualizing

momentum (adapted from Fig. 4, in Ulrich, 2014b, p. 32)

Heuristics

for critical contextualization (2):

"The moral idea

in context," or practicing moral universalization

It

follows from the preceding account that the situational meaning of the moral idea

is a function of how (and how carefully) we bound the relevant

context and, at the same time and inseparable from it, how

much (and how carefully) we look beyond the context thus

bounded. To put it a bit differently, moral judgment is a function of the balance we find between

the divergent requirements of moral contextualization and

moral universalization. This differs from Kant's (1786, B1)

implicit formula of moral reasoning, according to which the

essence of moral

judgment consists in a good will, and a conforming maxim of

action, that withstands the universalization

test:

M

= f (U)

The

latter

assumption leads Kant (1786, B 51-53, 62, 70f, 81) to his notion of a "categorical"

imperative, which sees in (U) the necessary and sufficient criterion

of all moral judgment:

U!

Clearly,

a framework of critical pragmatism needs to extend this scheme

so as to give an equal place to the requirement of contextualization.

It needs, in other words, to contextualize the test of moral

universalization. Let us try.

Contextualization

tool # 2: extended formula of moral universalization

We can employ a convenient shorthand to

remind us at all times of the need for contextualizing the moral idea:

M

= f (C, U)

whereby

M =

moral reasoning about the situational meaning of the moral idea,

resulting in moral judgment;

C = contextualization,

resulting in a context of concern considered relevant; and

U =

universalization, resulting in enlarged thought looking beyond

the context of concern.

Accordingly, moral reasoning

is the deliberative process by which we clarify and bring

together the contextualizing and universalizing considerations

that inform a situational moral judgment. We can then explain our reasons for a

moral judgment in terms of these considerations, and can make

transparent remaining

doubts or possible counter-arguments related to these choices. We

can also qualify a moral judgment by pointing out alternative

possible ways to contextualize

and universalize it, thus recognizing the legitimacy of other

judgments and the limitations of our own. The M = f (C, U) formula can

thus also help us keep the discourse open. There is no such

thing as a definitive moral judgment, given the choices involved

in the two fundamental processes of contextualizing and universalizing

moral issues. The former demands a systematic effort of making ourselves and everyone

concerned aware of the contextual assumptions at work (C); the

latter, an equally systematic effort of enlarging

the picture thus gained (U) – "systematic," that is,

in that care is taken to identify and consider all options for

the choices involved and to unfold their implications for all

the parties concerned.

This

conception of moral issues is by now so deeply ingrained

in my understanding of the "moral point of view"

that alternatively, the short notation introduced earlier for

situational judgment in general is quite sufficient to remind

me of the suggested, extended formula of moral universalization.

It provides a most convenient way of reminding me of the double

movement of critical thought required, and moreover it has the

advantage of linking this understanding of Kant's universalization

principle back to the spectrum idea:

C <–> U

In

my personal experience, this short formula has proven its value

for driving my thinking towards an "Upanishadic"

kind of moral reflection, the focus of which is on unfolding the interdependence

of "this" and "that" morality – the pragmatic,

situational demands of concrete action for improvement (as measured

by the consequences) and the strict, universalizing demands

of the quest for moral rightness (as measured by the generalizability

of underlying norms of action).

The point, to be sure,

is that neither quest can be properly understood without

the other; both are indispensable ingredients of reflective

practice.

In

a further variation, the shorthand also permits putting a temporary emphasis

on one of the two requirements. If for example an account of

a moral issue does not appear to pay sufficient attention to

the specific situation,

then one will note:

C! <–> U

or simply

C!

that

is, contextualize! Conversely,

one may see a need to enlarge the picture and to invest more

effort and care in unfolding the moral implications in question

beyond the considered situation,

so one will write:

C <–> U!

or just

U!

that

is, universalize! Note that U! now has a a changed meaning as compared

to Kant's "categorical" imperative: as the

underlying, extended M = f (C, U) formula

makes clear, U! now presupposes proper contextualization. Even

if in real-world practice we may often find that increased emphasis

is required on either (C) or (U), the

two principles of course still depend on one another for meaningful application.

So neither U! nor C! is ever to be read as intending a one-sided

reliance on either principle, (U) or (C). A better idea is to

think of C! and U! as a matter of current emphasis, not

alternatives. In particular, the short notation U! should not have

us fall back on a one-sided attempt to practice (U) as a kind

of context-free moral universalization, as if moral reasoning could ever

be properly conceived in

terms of a universalizing

movement of thought only.

Implications

for moral theory and practice The point of the extended formula is indeed

that

the original, context-free formula is not practicable. At best it lends itself

to an abstract, if not idealizing, explication of the moral point of view for purely

theoretical purposes. This is what Kant and many contemporary

authors influenced by him (among them Mead, 1934; Baier, 1958; Rawls,

1971; Silber, 1974; Apel, 1980; Kohlberg, 1981; Wellmer, 1986; Habermas,

1990b, c;

Benhabib and Dallmayr, 1990; and Tugendhat, 1993) have attempted to

achieve

in various and often insightful analyses. But not even the most

insightful analysis can change the fact that moral universalization

describes an ideal, not a possible achievement. It is, as I

suggested elsewhere, perhaps a diagnosis of the problem

of grounding moral practice, but certainly not a solution (cf.

Ulrich, 2006, p. 56). Accordingly

absent are examples of practical application. I have concluded

from all these studies that the universalization principle (U) cannot carry the burden they

aim to assign to it, the burden of identifying

and justifying moral practice (see the detailed analyses in Ulrich, 2006b;

2009c, d; 2010a, b; and 2013a, and the brief summary of their

implications in Part 1 of the present series of essays,

Ulrich, 2013c, p. 11-16).

With

a view to supporting moral practice, (U) is probably better understood as a

standard for reflective practice in dealing with moral claims

– for meaning clarification and validity critique, that is – than as

a standard for justification. From a critical point of view,

no practical

maxim or norm of action should ever be assumed to live up to the

standard of being truly universal. It is therefore imperative

to focus on identifying and unfolding the deficits of

moral claims that are due to inevitable contextual presuppositions or de-facto limitations.

No vain attempt to universalize a specific norm of action, and

then to tie its justification to this attempt, can replace the

effort of critical contextualization. That is what we

need (U) for, no more, no less.

The

universalization requirement (U) will thus play its proper role

not as a standard of justification but as a critical counterpart of the contextualization requirement

(C). This is the role that the extended formula

means to capture. So when we say that (C) and (U) are complementary

movements of thought, we really mean to claim that each can

and should fulfil a critical role for

the other: (C) reminds us of the need to carefully specify

the situational meaning of the moral idea and to translate it into

actual practice, and (U) reminds us of the need to question the contextual

assumptions at work and see the big picture. There is a famous

remark in Kant's first Critique (1787, B75 and B314) about the complementary

roles of "intuition" (i.e., sense-experience) and "thought"

(i.e., concepts) in generating knowledge:

Thoughts

without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind.

It is, therefore, just as necessary to make our concepts sensible,

that is, to add the object to them in intuition, as to make

our intuitions intelligible, that is, to bring them under concepts.

These two powers or capacities cannot exchange their functions.

The understanding can intuit nothing, the senses can think nothing.

Only through their union can knowledge arise. (Kant, 1787,

B 75, similarly B314)

Echoing

this remark, we might say that

when it comes to practical reason, moral universalization without

specifying contextual assumptions remains an empty claim, just

as specifying the situational meaning of moral action without

unfolding its implications beyond the considered context remains

blind. (C) and (U) cannot exchange their functions; only together can they

help us ensure moral

practice.

To

do justice to Kant and Habermas, the reason why their conception

of moral questions looks so one-sided from our present perspective

is that they are dealing with a theoretical limiting case

– the ideal of complete moral justification – rather than with

the everyday issue of concern to us, of how we might systematically

approximate the intent of the moral idea in practice.

For theoretical purposes, that is, for understanding the ideal

nature of moral justification, Kant's categorical imperative

U! and the underlying universalization principle

(U) remain insightful and indeed indispensable. Similarly Habermas'

model of practical discourse and the role it gives to (U) as

a justificatory principle remain insightful as a theoretical

analysis of the conditions that in principle (i.e., under

conditions of complete rationality) would need to obtain to

secure sufficient (i.e., again, complete) moral justification

of norms of action. For such theoretical ends, (U) probably

still provides an indispensable explication of what we mean

by the moral point of view (Baier, 1958). Moreover, (U) can

be said to capture a widely held,

intercultural and everyday understanding of morality, to which

we have referred with terms such as "reciprocity"

and "fairness" and according

to which we should not treat other people in ways we would not

want them to treat us – the age-old golden rule. In simpler terms, we should

not rely on norms of action that we do not respect ourselves.

That is, we should not claim an exception for

ourselves (cf. the detailed discussion in Ulrich, 2009b,

pp. 28-32).

It

is clear, then, that the difficulty we have with Kant's and

Habermas' focus on U! concerns not its theoretical

merits but its practicability under real-world conditions

of imperfect rationality. The idealizing role they give to (U)

is not altogether wrong but too strong, because too one-sided.

Such one-sidedness neglects that fact that moral universalization

and moral contextualization each gain their essential methodological role in

response to the other, namely, as a critical corrective

for each other's inevitable deficits. Only together can they

help us assess the moral merits and deficits of practice.

Two

examples It is time to test the relevance

of moral contextualization, and thus the suggested, extended

formula of moral universalization, by means of two practical

cases. The first reconsiders Kant's moral analysis of lying;

the second deals with the contemporary issue of passenger planes

employed for terrorist attacks.

First

example: Kant's analysis of the moral unacceptability of lying

As it happens, one of Kant's

(1797) own examples for the use of U! demonstrates

that the extended formula is required. I refer to his famous

discussion of the moral problem of lying by means of what has

become known as the case of

the inquiring murderer. I have discussed this example in an

earlier account of Kant's position (see Ulrich, 2009b, pp. 32-35) in quite some detail

and thus can keep the present discussion rather short.

Imagine,

Kant asks us, that a murderer confronts you with a situation

in which his victim's life depends on whether you lie to him

or stick to the categorical imperative, which (as Kant thinks)

allows no exception from the moral demand of not lying:

|

The

Case of the Inquiring Murderer

Source:

Kant (1797, A302, with reference to B. Constant, 1797,

p. 123);

previously discussed in Ulrich (2009b,

pp. 32-35).

|

|

Suppose

you have allowed a person fleeing from a murderer to

hide in your home. Then the murderer knocks at your

door and asks you whether that person stays in your

house. Should you tell him the truth or lie?

|

Does such an extraordinary

situation permit an exception from the duty not to lie?

How should we handle the difficult alternative of either being truthful

or (preferably, it would seem) rescuing someone's life at the expense of an exception? Kant's

answer is not what one might expect. There

must be no such exception, he maintains; for any other stance would

clash with the categorical imperative, according to which the

maxim of one's action must be universalizable. Lying with a

view to helping another person cannot be a universalizable maxim.

If the exception were admitted, say, with reference to its altruistic

nature or to the duty of helping, we could never again be certain that others are

telling us the truth, unconditionally so, or whether for some altruistic

motive they might be lying. Even the act of lying would become meaningless;

Kant argues; for its effectiveness, too, depends on the universal prohibition of lying. These

implications reveal for Kant how self-defeating

any exception to the principle of not lying, or to any other principle

recognized as right, would be. U! as applied to

the prohibition of lying is thus for him indeed a "categorical"

(unconditional) imperative; so much so that even just considering

the possibility of some occasional exceptions (i.e., the option

of reserving for oneself the right to

claim an exception) is wrong. (Kant, 1797, A301-314)

One

must wonder whether such an employment of the universalization principle

(U) is sound. As we observed at the outset, moral issues often arise

in situations of ethical conflict in which two ethical goods

clash. This is also the case in Kant's example, where the duty

of truthfulness conflicts with the duty to help someone in acute

danger. The task of moral reasoning is then to handle such situations

in ways that protect the dignity and integrity of human beings,

and indeed (in my personal view) of all living creatures. Putting

someone's life at risk where this risk could clearly be avoided

or reduced, violates this core concern of the moral idea and

is thus hardly a unversalizable way of handling the situation

that Kant describes. His conclusion therefore suggests to me

that something is wrong with his answer. What I think is wrong

is not his strict adherence to the universalization principle

(U) as such but rather, his failure to adequately contextualize

the maxim of action that he subjects to its test. In the shorthand suggested above,

our response to Kant's account can only be: C!

Our

diagnosis of what is wrong with Kant's example is then clear.

Kant overemphasizes the role of (U) as compared to that of (C).

Doing so leads to inadequate results of the universalization

test. To put it more bluntly: it makes little sense to try

and universalize

norms that have not been properly contextualized in the first

place. The maxim that Kant subjects to the test of (U),

and then rejects on this basis, is something

like this:

"Lying

is permissible for altruistic reasons."

This

maxim fails the universalization test, rightly so, as it formulates

the condition for exemption from the prohibition of lying far

too openly. The question

is whether this way of specifying the maxim captures the situation

adequately. I don't think so. Applied to the situation in question,

the result is that a human life is sacrificed without absolute

necessity. Kant tacitly accepts this consequence without commenting

on it, as his focus is on not violating the universalization principle.

By implication, the norm of action

that for Kant does not fail the test, and according to

which he therefore wants us to act, reads:

"Refuse

to save another person's life if doing so requires you to lie."

The

result would have been different if Kant had reformulated the

maxim to be tested so as to better capture the ethical conflict

with which the situation confronts us. For example, he might

have submitted to (U) the following, more carefully contextualized

maxim:

"As

a matter of principle, do not lie; but if the situation is such

that you cannot save a person's life except by lying, choose

to save that life."

If

a core concern of moral action is to protect the integrity and

dignity of others, as Kant never tires to emphasize, a thus

specified maxim would indeed have passed the test. Counter to

what Kant suggests, then, I would argue that his example demonstrates

not so much the "categorical" (i.e., unconditional

and universal) character of the moral prohibition of lying but

rather, how important it is for sound moral reasoning to carefully

consider the specific situation. The example in fact illustrates

what our extended formula is all about: universalization can be an unconditional moral requirement

only inasmuch as we properly contextualize the maxims to which

we apply it. Hardly any practical norm of action is indiscriminately

meaningful and valid for each and all situations, except perhaps

the moral principle (U) itself, which for exactly this reason

is not a practical norm of action but merely a standard for

examining such norms.

Second example: hijacked passenger planes My

second example relates

to a serious contemporary issue, the threat of terrorist attacks

using passenger planes. We all have in mind the

incredible pictures of the terrorist attacks in the United States

of 11 September 2001, an event now often referred to as 9/11

or Nine-Eleven, when four passenger planes were hijacked in a coordinated

action and used to attack the twin towers of the World Trade

Center in New York along with other targets. At that time, such

a use of passenger planes was unprecedented and there were no

adequate preparations for the situation. Today many countries

have plans for their air force to shoot down such planes before

they reach possible targets. However, difficult moral questions

are involved, which can be summed up as follows:

|

The

Case of a Hijacked Passenger Plane Used as a Weapon

Source: Interactive

TV version of the theater play "Terror"

by Ferdinand von Schirach (2015/16), a German defense

lawyer who is also a writer, broadcast simultaneously

with discussion

and voting by the audience in three German speaking

countries (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland)

on 17 Oct 2016.

|

|

Suppose

a terrorist has hijacked a plane with 164 passengers

and crew flying from Berlin to Munich and intends

to let the plane crash into a football stadium in

Munich, where 70,000 spectators are following

a match between England and Germany. Two fighter

planes rise to the passenger plane but receive no order from their

superiors to shoot the plane down, nor any other

specific instructions. As the planes

approach Munich, the fighter pilot in charge has to take

a decision. He decides to shoot down the plane,

that is, to sacrifce its passengers and crew, so

as to save the 70,000. Later he finds himself in court,

accused to have murdered 164 people on board of

the plane. As a member of the court, should you pronounce

him guilty or innocent? And how would you have decided

in the pilot's place?

|

As

the tribunal unfolds, it becomes clear that the pilot had a

difficult decision to take and was left alone with it. His

superiors on the ground hesitated to act against a previous

decision by the Supreme Court, according to which shooting down

such planes violated the Constitution's fundamental principle

of the protection of human dignity. It equally becomes clear

that the pilot, who like his superiors was aware of this court

decision, was caught in a dramatic ethical conflict between

sacrificing the people on board of the plane or risking the

lives of the 70,000 in the stadium. His conscience told him

to opt for the lesser of the two evils, even if it was against

the Superior Court's earlier decision and thus meant he would

be tried and might be found guilty of murder.

During

the court hearing, many contextual elements – some of them rather

surprising – come to the fore that were not known or clear to

the parties from

the outset but which are clearly relevant

for judging the situation in which the pilot found himself,

both from a moral and a legal point of view. Our focus, like

that of the stage play and the TV broadcast, is on the moral

aspects.

Here are some of the contextual considerations that

the court takes up, although with varying degrees of attention

and elaboration; I have ordered them approximately in a left-right

order within the (C) <–> (U)

spectrum (Box 1):

|

Box

1: Contextual

considerations

1.

We are dealing with a situation of extreme urgency

in which the agent – the pilot in charge of the

mission – was left alone. Under enormous time pressure

and with no adequate support by his superiors on

the ground, he had to choose between two moral evils:

either he pushed the button or he didn't, in both

cases people would die, there

was no third option.

2.

In the situation in which the pilot found himself,

he had to rely on his personal conscience. He knew

there had been a Superior Court ruling against shooting

down hijacked planes, so that shooting down the plane might mean going to prison

for him. He could be said to have assumed a responsibility that strictly

speaking was not his, but which from his view he

had no way to avoid. It became his responsibility,

as he saw it, due to a lack of adequate instruction

and support from the ground staff.

3.

There can be no doubt of the pilot's good will to

act as morally as possible. He certainly cannot

be accused of having risked the lives of people

out of selfish motives; quite the contrary, he consciously

risked a prison sentence. His motivation can thus

be called altruistic. Had he thought of his

own interest first, he would have opted for inaction

(i.e., not shooting down the plane), thereby risking

the lives of 70,000 innocent people on the ground

and thus (as his conscience told him) causing even

more suffering.

4.

His moral conscience told the pilot that

it was worse to risk the lives of 70,000 people

in the stadium than those of 164 passengers and

crew on board of a plane. The court

ruling in question was therefore, as he saw it, wrong or not properly applicable to the

situation. He also found the court ruling wrong for a second reason: it meant that terrorists could in future

be sure that on board of a hijacked place they would

be safe.

5.

The pilot's motives can also be

said to have been impartial, as he had no information about who was in the

passenger plane and who in the stadium.

He clearly did not act so as to protect (i.e.,

privilege) people he knew, whether in the passenger

plane or on the ground.

6.

The decision authorities on the ground

could have changed the situation decisively if they

had decided early on to evacuate the stadium and

all other potential targets of the terrorist, rather

than relying solely on the pilot's decision. In

this respect they appear to be jointly responsible

for what happened. So as soon as we include the

air force staff in the relevant context, a major

share of the responsibility for the loss of lives

is no longer the pilot's only.

7.

The pilot further considered, as he told the court,

that if he

opted not to

take any action,

the terrorist would hardly see this as a reason to

abandon his plan and instead to allow the passenger

plane to land safely. The fighter pilot's decision

would thus not affect the

passenger plane's likely destiny in a significant

way. The decision he had to take was not whether to sacrifice

a smaller or a larger group of people but rather,

the smaller or both groups. To the extent

this reflection is accurate, the decision would

amount to a truly universable maxim of action. But

of course, there can be no certainty as to how the

terrorist might have acted.

8. Still,

instrumentalizing the people on board of the hijacked

plane for the sake of other people was morally wrong,

whatever situational considerations supported the

decision.

The value of human lives cannot be measured quantitatively.

Trading in the lives of the 164 passengers and

the crew against the 70,000 lives at risk in the stadium

might be considered utilitarian rather than moral

reasoning, as it fails to do justice to the dignity

of the people on board of the plane.

9. Although the principle of shooting down hijacked

passenger planes used as weapons is not morally

universalizable, the contrary principle of allowing

their use as weapons is not universalizable either.

Inaction does not protect from responsibility

in such a case, both legally and morally speaking.

Just imagine the pilot would have remained inactive

rather than facing the decision he had to take;

could he then not have been rightly accused of failing

to protect the lives of the 70,000 in the stadium?

|

Such

contextual considerations, even if tentative, are apt to illustrate

that the principle of moral universalization

is indeed a general idea that as such tells us little about a moral issue.

There is no way round identifying and weighing the ethical conflicts

involved. The process of deliberation required may vary in terms

of complexity, as our two examples show; but in any case it

involves

acts of personal conscience along with rigorous thought about

a course of action's implications beyond the situation at hand. It

should be clear, then, that reference to personal conscience in weighing

situational aspects does not make universalizing (or decontextualizing)

reflection redundant, just as the latter will not yield a valid

result unless we carefully contextualize the maxim to be tested. The extended

formula:

M

= f (C, U)

can

remind us of this double requirement. By implication, the value of the

universalization test depends crucially on how well a tested

maxim of action captures

the specific situation.

In the present case, a

simple, general rule that hijacked planes have to be shot down

to prevent such

terrorist attacks would not do justice to the specifics of the

situation,

in fact it fails to consider it altogether. The crux of the

situation is that by the time the pilot finds himself obliged

to take a lonely decision, the situation has evolved so that

whatever he decides,

some lives are in peril. Due to a lack of timely action

by the ground staff, the question no longer is whether people

are getting instrumentalized but only who and according to what criterion.

The maxim to be tested must somehow try to capture this situation.

Perhaps a specific maxim such as the

following might come closer to capturing the situation:

"If

you find yourself in a situation in which you cannot avoid the instrumentalization of

some people's lives, act so as to minimize the number of people

affected."

The

underlying, more general norm of action would then be:

"If

you find yourself in a situation in which you cannot avoid to

opt for one of two evils, neither of which can be avoided due

to lacking time or other circumstances, choose the lesser evil."

However,

while

thus contextualized norms of action recognize the ethical conflict

involved, they do not free the person who faces the situation

in question from the need for taking a personal decision and

accepting responsibility for the harm it may cause. How, then,

readers may wonder, did the court decide the case?

The play

handles the question in a sophisticated and consequent manner.

Sophisticated, in that it presents two highly engaging summations

and pleas by the public prosecutor and the defense attorney;

both argue brilliantly, though in opposite directions, thus providing the jury

and the audience

with much food for thought. Consequent, in that

the jury then retires for its deliberation – guilty or not

guilty? – and meanwhile leaves the people in the audience with

a need for taking their personal decision. The audience has

to vote before knowing the court's judgment and the underlying

reasoning, for the continuation

of the film depends on how the audience decides. In this sense

the film's plot is interactive. Dependent on the

vote of the audience, the president of the court will declare

the jury's sentence and will explain it in terms of either the

prosecutor's or the attorney's core argument.

Should

the audience decide that the pilot is indeed guilty, the sentence

will follow the prosecutor's core argument:

Human

lives must never, not even in extreme situations, be weighed

against one another. That would violate the fundamental principle

of human dignity which informs our Constitution and our basic

norms of living together in an open and just society. (von Schirach,

2015/16; final scene if the audience finds the pilot guilty;

freely rendered court opinion as explained by the judge)

Should

the audience decide that the pilot is not guilty, the sentence

will adopt the attorney's core argument:

The

law is not able to solve all moral problems unambiguously and

consistently. We have no legal criteria to ultimately judge

the pilot's moral decision, which therefore has to remain a

matter for his conscience to decide. The law leaves him alone.

It would therefore be wrong to condemn him. (von Schirach,

2015/16; final scene if the audience finds the pilot not

guilty; freely rendered court opinion as explained by the

judge)

Both

arguments are strong and needed, neither is sufficient for an

adequate understanding of the issue. The first opinion is grounded

mainly in (U), the second mainly in (C). Unlike in the previous

example, there is no unequivocal answer in this case. One finding

is clear though: Kant's formulation of the moral imperative

in terms of

M

= f (U)

cannot

give us the answer. It's precise meaning

remains unclear in both examples, but especially in the pilot's situation, as both options he faces fail the universalization

test. It is not possible to understand the situation without

accurate contextualization, which requires a personal weighing

of considerations such as those listed above. Conversely, such contextual considerations alone cannot

provide a sufficient

basis for moral judgment either, as there clearly is a need for reference

to some general standard of human dignity and interpersonal

fairness that is independent of such considerations and can

be shared by all people of good will.

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

PDF file

Note: Our

exploration of

the role of general ideas in rational inquiry and practice continues

with some basic considerations, inspired by Upanishadic thought,

on how to practice a critical contextualization of general ideas.

The previous

essays of the series appeared in the Bimonthlies of

September-October 2013, January-February

2014, July-August 2014, September-October 2014, November-December

2014, March-April 2015, May-June 2015, and September-October

2015. There will be one more and final essay to conclude the

series.

|

|

|

References (cumulative)

Abbott,

T.K. (1885). Kant's Introduction to Logic and His Essay

on the Mistaken Subtilty of the Figures. London: Longmans, Green

& Co. 1885; on-line facsimile edition.

[HTML] http://www.archive.org/stream/kantsintroductio00kantuoft#page/n3/mode/2up

Apel,

K.O. (1980). The a priori of the communication community and

the foundations of ethics, in K.O. Apel (1980), Towards a

Transformation of Philosophy, London: Marquette, pp. 225-300.

German orig.: Das Apriori der Kommmunikationsgemeinschaft und

die Grundlagen der Ethik. In K.O. Apel, Transformation der

Philosophie, Bd. 2: Das Apriori der Kommunikationsgemeinschaft,

Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1973, pp. 358-436.

Apte, V.S. (1890/2014). The Apte

1890 Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Based

on the Apte Sanskrit-English / English-Sanskrit Dictionary,

3rd. edn. Poona: Prasad Prakashan, 1920. Searchable online edition

by the Cologne Project, Institute of Indology and Tamil Studies,

University of Cologne, Germany, 2014 edition.

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/AP90Scan/2014/web/index.php

Apte, V.S. (1920/2014). Apte English-Sanskrit

Dictionary. Based on the Apte Sanskrit-English / English-Sanskrit

Dictionary, 3rd. edn. Poona: Prasad Prakashan, 1920. Searchable

online edition by the Cologne Project, Institute of Indology

and Tamil Studies, University of Cologne, Germany, 2014 edition.

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/AEScan/2014/web/index.php

Apte, V.S. (1965/2008). The Practical Sanskrit-English

Dictionary. 3 vols., Poona, India: Prasad Prakashan, 1957-1959.

4th, rev. and enlarged edn., Delhli, India: Motilal Banarsidass

Publishers, 1965. Online version, last updated in June 2008.

[HTML] http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/apte/

[HTML] https://archive.org/stream/practicalsanskri00apteuoft#page/n5/mode/2up

(facsimile of 1965 edn.)

Arendt, H. (1958). The Human Condition.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Aristotle (1985). Nicomachean Ethics. Translated,

with Introduction, Notes, and Glossary, by Terence Irwin. Indianapolis,

IN: Hackett.

Aurobindo, S. (1996). The Upanishads

: Texts, Translations and Commentaries.

Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Light Publications (orig. 1914;1st US

edn.).

[PDF]

http://www.aurobindo.ru/workings/sa/12/isha_e.pdf

(transl. of Isha Upanishad)

Austin,

J.L. (1962). How To Do Things With Words. The William

James Lectures, delivered in Harvard University in 1955. Oxford,

UK: Clarendon Press/ Oxford University Press. (2nd ed. 1976).

Baier,

K. (1958). The Moral Point of View: A Rational Basis of Ethics.

Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Abridged edn., New York:

Random House, 1965.

Beck , U. (1992).

Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

Beck, U. (1995). Ecological Politics in an Age

of Risk. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Benhabib,

S., and Dallmayr, F. (eds.) (1990). The Communicative Ethics

Controversy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bok, S. (1993). Foreword. In M. Gandhi

(1957); An Autobiography: The Story of my Experiments With

Truth, Boston, MA: Beacon Press (reprint edn. of the orig.

1957 edn.,with this new foreword). Boston, MA: Beacon Press,

pp. xiii-xviii.

Böthlingk, O.,

and Roth, R. (1855). Sanskrit-Wörterbuch. Herausgegeben

von der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Sanskrit-German

Dictionary. So-called Grosses

Petersburger Wörterbuch [Greater St. Petersburg

Dictionary, 7 vols.].

St. Petersburg, Russia: Kaiserliche

Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1855-1875.

[HTML]

http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/PWGScan/disp2/index.php

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/pwgindex.html

( facsimile

reprint edn)

Böthlingk, O.,

and Schmidt, R. (1879/1928). Sanskrit-Wörterbuch in

kürzerer Fassung. Herausgegeben von der Kaiserlichen

Akademie der Wissenschaften. Sanskrit-German Dictionary. So-called

Kleines Petersburger

Wörterbuch [Smaller St. Petersburg Dictionary].

St. Petersburg, Russia: Kaiserliche

Akademie der Wissenschaften, two parts, 1879-1889, mit Nachträgen

von R. Schmidt, 1928.

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/scans/PWScan/disp2/index.php

[HTML] http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/pwindex.html

[HTML] https://archive.org/stream/sanskritwrterb01bhuoft#page/n3/mode/2up

(facsimile of Part 1, 1879 edn.)

Bowker, J. (ed.) (2000).

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Oxford,

UK: Oxford University Press.

[HTML] http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O101-Brahmansatyamjagatmithya.html

Carnap, R. (1928). Der logische Aufbau der Welt.

Leipzig, Germany: Felix Meiner Verlag. English transl. by R.A.

George: The Logical Structure of the World: Pseudoproblems

in Philosophy, University of California Press, 1967 (new

edn. Chicago, IL: Open Court, 2003).