|

|

|

<<

Continued from Part 1/2

Selectivity,

not comprehensiveness, is the fate of all practice.

(W.

Ulrich, "Philosophy for professionals: towards

critical

pragmatism," 2007b, p. 2)

A

Plea

for Boundary Critique:

Recapitulation

Based on a review of some major contemporary ideas on active citizenship, competent

professionalism and management, and systems thinking, Part 1

identified a fundamental deficit of conventional systems rationality

in its failure to come to terms with the inevitable selectivity of all human practice

– the basic insight that no human effort can claim to be comprehensive

in its outlook and rationality and to live up to everyone's interests and concerns equally.

Today's prevailing framework of systems thinking lacks

a systematic conception of the divergent reference systems or

"contexts that matter" for identifying relevant knowledge

and rational action. Its focus on the system/environment

distinction, that is, on a system of interest and the environmental

conditions on which it depends, is oriented one-sidedly towards

the success of what is regarded as system of concern, as distinguished

from all other concerns that may be at issue – ranging from the

specific concerns of third parties that, although being affected,

are not involved in or relevant to the system in any way, to

the universalizing perspectives of morally defensible and ecologically

sustainable reasoning. In particular, contemporary systems thinking

fails to systematically consider what we called the context

of application (or context of responsible action), that

is, the real-world context in which the consequences of systemic

rationality arise and its value implications become apparent,

not only for the parties who have a say and are to benefit but

also for all those who don't.

The result

of

this failure

is an impoverished rationality that we encounter at work everywhere

around us. It is omnipresent in our epoch's ongoing

process of rationalization, and particularly in the corporatist

and bureaucratic organization of the society it has brought

about, a society in which the actual sources of power and legitimacy

lie much more with vested interests and global corporations

than with the citizens. Worse, the impoverished, managerial

and functionalistic

nature of this surrogate rationality – a rationality grounded

in references to "the system" of interest and its

relevant environment only – can hardly be said to be obvious

and

clear to a majority of citizens, professionals,

and decision-makers, and accordingly to be under broad and thorough

scrutiny. We have in this respect become an

unconscious civilization (Saul, 1997), in which it seems

normal that people understand (and are expected to understand)

as "rational" that which works for the systems of

(vested) interests in which they are involved or of which

they are accountable as managers.

A

rationality perspective grounded in references to the context

of application is markedly different from such a managerial

perspective. It accepts accountability for the consequences

of systemic rationality regardless of where they arise and whom

they affect. It

stands for a moral point of view in dealing with the inevitable deficits

of justification of these consequences and the manifold ways

in which they may affect those concerned. By dealing openly and carefully

with such deficits, it brings into the picture a critically-normative

perspective. It thus complements the success-orientation of a systems

rationality grounded in the system/environment

distinction (What serves the system?) with a fundamentally different orientation

towards ethical awareness (What is conducive to improvement

as seen from the standpoints of all those concerned?) and moral

reasoning (What is arguably fair as seen from an impartial and

universal point of view?) – a perspective that takes up the concerns

of those affected but not involved and asks what "success"

means for them, that is, how their interests are

treated.

Given

the enormous influence of systemic thinking on many fields of

professional practice, it should not surprise us that this deficit

of conventional systems theory has had and continues to have

serious consequences. We encounter here a fundamental reason

of why rational, professionally and scientifically based decision-making so often produces external irrationalities such

as unexpected side-effects, undesirable long-term

effects and unsustainable policies, costs and risks imposed on third parties, and

so on – in short, omnipresent suboptimization

and deficits of rationality and legitimacy. Its consequences

are then symptomatically treated as "external"

effects that one cannot all foresee and about which one cannot do a lot.

They are "external," indeed,

to the systems rationality of those involved but not of course

for those who have to live with them.

Such

externalities are omnipresent today. They have prompted the

German sociologist Ulrich Beck (1992; 1995) to describe the dilemma of modernity in

terms of a Risk Society, that is, a society whose processes

of rationalization produce risks for whom nobody

seems to be responsible – a case of organized irresponsibility

(thus the 1995 book's original title, lost in the English translation).

However, despite the immense attention that Beck's diagnosis received,

a methodologically clear, systematic and rigorous treatment

of the context of application, and particularly of its normative

content, is still largely missing in the applied

disciplines to this day.

In the

CSH framework that I propose for such critically-normative practice,

any claim to systemic

rationality calls for empirical and normative scrutiny of its selectivity,

that is, its different implications

for all the parties concerned – not only for those involved but also for those

affected but not involved (so-called third parties). The key methodological principle is boundary

critique, a systematic process of laying open the situational

boundary judgments that delimit

the contexts considered relevant (whether consciously or not) in claims to knowledge, rationality,

and improvement, or in short, the borders of concern.

As this recapitulation should help readers recall,

four essential kinds of contexts were introduced in

Part 1, understood as "reference systems" to which

such claims cannot avoid referring, whether explicitly or implicitly,

and which therefore offer themselves for a systematic analysis

of selectivity: the system (or situation) of primary interest

S; the relevant environment (or decision-environment) E; the

context of application (or of responsible action) A; and the

universe (or total conceivable universe of discourse) U. Together

they make up the proposed

S-A-E-U formula (or scheme) of boundary critique. Critical systems thinking and practice as I understand

them will make boundary critique with reference to these four

reference systems an integral part of the quest for competent

and self-reflective

practice. It is now time to explain how boundary

critique works.

Critical

Systems Heuristics We have understood that the fate of all human

inquiry and practice is selectivity, not comprehensiveness.

This selectivity can be traced to the boundary judgments by

which we delimit the reference systems for rational practice

or, in everyday terms, decide what is part of the picture we

consider and what is not. In

principle, of course, sound reasoning has to take into

account "everything" potentially relevant, otherwise it becomes

arbitrary. In practice, though, we don't know what that means.

The quest for comprehensiveness

is an ideal that we may strive to approximate but will

not fully realize. Hence, we should never assume or claim that

we do live up to it. How, then, can we still hope to secure sound argumentation

in everyday and professional practice? What can rational practice

mean under such conditions? This is the basic problem with which

CSH tries to come to terms.

Since

we are referring to an ideal, it follows that no solution can at

the same time be theoretically sufficient and practical. All theoretically sufficient

solutions will of necessity rely on ideal presuppositions, whereas

all practicable solutions will be incomplete, that

is, selective,

and thus disputable. In practice, the best we can hope to achieve

is cultivating reflective practice with respect to the selectivity

of our claims, by making it clear to ourselves

and to all others concerned on what boundary assumptions they

rely. Further, we will have to recognize that inasmuch as our claims serve

as a basis for action, their selectivity translates into partiality:

they will not respond equally to the different concerns of all the parties and in this sense

are "partial" – they will promote some rationalities

and conforming notions of improvement more than others, and

thus benefit some parties more than

others. The

conflicts of views and concerns that often arise around efforts

to resolve practical issues have a lot to do with this translation of (inevitable)

selectivity into (changeable) partiality. It explains the inherently normative nature of all claims to rational

practice. Unlike the current "reflective practice"

mainstream (see Ulrich, 2008, for a critical view), CSH seeks

to find rigorous ways for unfolding this normative core of practice.

Unfolding

selectivity: the "eternal triangle" of boundary critique When

ordinary citizens face professional researchers or experts, it can

be difficult for them to defend their personal views and concerns against

the claims of the specialists. Indeed, how can

non-specialists dare to argue against the specialists and prove

them wrong, given that the specialists have such an advantage

of information, status, and routine?

As the idea of boundary critique helps

us to understand, the answer is simple: they don't have

to. There is in fact no need for proving anyone

wrong. It is quite sufficient for cogent critical argumentation

to demonstrate that there are

always options for defining what counts as relevant knowledge and right action

– the "facts" and "values" to be considered

– because there are options for delimiting the reference system

to which such claims refer, that is, the situation or context

that matters. Whether the claims in question are those of professional

people or of lay people makes little difference in this respect.

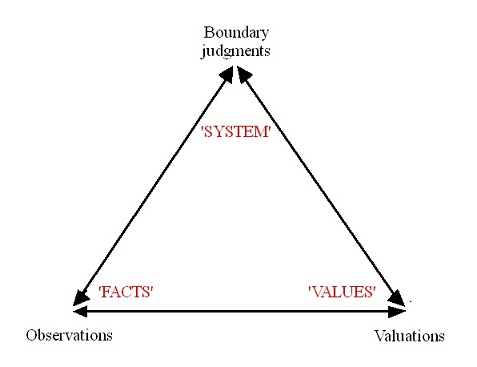

We face, as CSH describes it, an eternal triangle of

practical reason (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: The eternal triangle of boundary critique

The

boundary judgments by means of which we delimit our

reference systems condition the facts and values we recognize

to be relevant. Conversely, new facts or values can prompt us

to revise previous boundary judgments, which then in turn may

have us see previous observations or evaluations differently,

and so on.

Since boundary judgments act as mediating third between

judgments of fact and of value, surfacing them helps us understand

not only the nature of their selectivity but also how they depend

on one another.

(Sources:

Ulrich, 1998, p. 6; 2000, p. 252; and 2003, p 334)

The

basic idea is that three major types of judgments inform all claims to knowledge,

to rationality, improvement, morality, and so on

– judgments of fact, judgments of value, and

boundary judgments. While the former two kinds of judgments

are well known, the latter are often ignored, be it because

people are not aware of their existence or because they deliberately

conceal them from others. Together, the three types of judgment make up

– and explain –

the selectivity of practical claims. This is what the eternal

triangle of CSH is all about. Accordingly three essential

– and interdependent – questions pose themselves in all rigorous

thought and argumentation on practical issues:

- What

observations and resulting judgments of "fact" or relevant

circumstances and interdependencies matter? (e.g., for understanding the situation or issue at hand or

for effective and efficient action);

- What

valuations and conforming judgments of "value"

or relevant notions of

improvement are to guide us? (e.g., for improving the situation

or for evaluating the results of action);

and new,

- What reference

systems (S-E-A-U) and specific boundary judgments

are to define the relevant context or situation? (e.g., for

delimiting the system of primary interest S from the decision-environment E,

or the context of responsible

action A from the universe U of all conceivable consequences).

The

additional concept of boundary judgments explains the way

in which all our judgments of fact and of value are interdependent,

namely, via shared assumptions about the reference system to

be considered

(S-E-A-U) and the specific boundary issues involved. It is no

news of course that facts and values

are interdependent; but the precise nature of this interdependence

usually remains fuzzy and unexplained. The eternal triangle

now makes this clear. It explains why both the circumstances

we consider relevant and the ways

we evaluate them – the considerations

of fact and value we take to matter – depend on boundary judgments,

that is, assumptions as to which situational aspects are to

be treated as belonging to the situation of concern (or the

"system" of primary interest) and what other aspects

are to be treated as relevant environment (or decision-environment)

and/or as context of application (or context of responsible action). When

boundary judgments change, new circumstances may emerge

to be relevant, which in turn may require us to adapt our

value judgments; conversely,

changed notions of improvement may change our appreciation of

what are relevant circumstances and thus may have us revise

our boundary judgments, which then

in turn makes previous evaluations look different, and so on.

An

untapped emancipatory potential By

reminding us of the conditioned character of all our judgments, the eternal triangle has

us deal more consciously and carefully

with the pervasive issue of selectivity. Just as importantly, it helps us to

understand

– and to explain to others – why in dealing with selectivity, specialists and

non-specialists can meet

at eye-level: when it comes to

making boundary judgments, experts and professionals have no

natural advantage of competence over lay people. This is so

because professional

expertise does not protect against the need for making boundary

judgments but depends on them just like everyday

knowledge. Nor, to be sure, does it provide an objective or

in other ways superior basis for defining

boundary judgments. Boundary judgments cannot be separated

from value judgments, but professional knowledge provides no

claim to superior value judgments. The only kind of superiority

to which boundary judgments lend themselves is with respect

to their transparent and self-reflective handling. Once we recognize

the role of boundary judgments, we are compelled to take the

critical (or critically-heuristic) turn, that is, to recognize

that there can be only a "critical solution" to the

quest for practical reason.7)

I

see in this critical consequence of the systems idea a largely untapped potential

for giving ordinary citizens and managers a meaningful new competence

vis-à-vis experts and professionals. Since relevant facts change

with boundary judgments, and vice-versa; and since new facts

or different boundary judgments may make us reconsider our values,

that is, the way we evaluate facts, it is clear that boundary

judgments strongly influence the outcome of professional as

well as everyday discourse. Together, the three types of judgment

involved – judgments of fact, value judgments, and boundary

judgments – indeed form an eternal triangle that is always in

play and which nobody claiming adequate knowledge and

understanding has consequently

a right to ignore. Since it does not allow of any definitive solution,

the only arguable way to handle it is by democratically legitimate

decision-making based on systematic and open processes of boundary

critique – open, that is, for all those concerned. Boundary

critique cannot of course preclude that those in a situation

of power suppress or close the discussion on boundary assumptions

by non-argumentative means; but at least, boundary critique

then provides a means of rational critique by which the reliance

on such non-argumentative means can be exposed. When the façade

of professional objectivity crumbles and everyone becomes aware

of the role of boundary judgments, it also becomes apparent that

there are options for what counts as relevant knowledge,

rational action, and genuine improvement.

It

is indeed quite frequent that experts and decision-makers are

as unaware of the role of boundary judgments, and hence of the

need for boundary critique, as are ordinary citizens. They may

be more or less aware of the element of choice and selectivity

involved in their "findings and conclusions" yet prefer

not to emphasize the circumstance too much, as they don't know

how to deal systematically with it. It is so much easier

for them to claim superiority or even "objective necessity"

for their judgments, due to their particular expertise and status.

But as the concept of boundary critique makes clear, such references

to superior insight move on slippery ground. People who have

understood the idea can use boundary critique to expose the

selectivity of the claims in question and the element of choice

involved. We encounter here a situation

in which lay people and professionals can indeed meet at eye-level.

When it comes to a transparent and self-reflecting handling of

the eternal triangle, we all meet as equals.

Towards

symmetry of critical competence The epistemological

implications of this concept of boundary judgments are significant.

It means that in spite of the usual asymmetry of knowledge and

skills between ordinary citizens and professional people there

exists, at a deeper layer, a fundamental symmetry between them.

At this deeper layer, professional people are in a situation

that is no different from that of lay people. Their professional

judgments depend no less on boundary judgments than do everyday

judgments. Critical systems thinking thus teaches us a truly

important lesson in citizenship: below the surface of

expert knowledge and professional behavior, there exists a deep

symmetry of all claims to knowledge and rationality, whether

professional or not. They all depend on boundary judgments that

cannot be justified by reference to expertise. Accordingly,

this deep symmetry has

implications not only for the practice of research and expertise

but also for the practice of democracy. Rationality and democracy

need not be opposites, after all!

The critical kernel that

we associate

with systems thinking thus unfolds into a fundamental emancipatory

potential. The question is, can we realize this potential? Can

we translate it into strategies for training citizens in citizenship,

without presupposing cognitive skills that are not available

to most of them?

With

a view to meeting this democratic and emancipatory challenge, it

will be important not to fall back upon

a concept of the "competent" citizen that would once

again

exclude a majority of ordinary people. Present conceptions

of systems thinking, due to their focus on the use

of research and professional methods, do not always avoid this kind

of elitist implication, not any more than contemporary notions

of professionalism. Critical systems thinking for professionals

and citizens

should avoid this pitfall from the start. It must not make competent

practice depend on any special competence that would not be

available to ordinary citizens. Citizens are not, and will probably

never be, equally

skilled; but in democracy this fact must not make any difference

to their equality as citizens, according to the principle:

"one citizen, one vote."

Three

uses of boundary critique It

is the goal of critical systems heuristics (CSH) to develop

such an emancipatory systems approach. After what has been said

thus far, even readers not familiar with critical heuristics

will probably anticipate that one of its core concepts for achieving

its end is a process of systematic boundary critique,

and that the main vehicle driving this critical process is the

critical employment of boundary judgments, by which I mean both

their self-reflective use and their critical use against not

so self-reflective assertions of boundary judgments (Ulrich, 1983, pp.

225-314; 1987; 1993). The idea, briefly, is that boundary judgments

offer themselves for three kinds of critical employment, in

three corresponding settings for boundary critique:

(1) Boundary reflection, that is, promoting

reflective practice through boundary-questioning self-reflection: What boundary judgments

do I/we presuppose? What is their selectivity

as measured not only by the facts and values they exclude but

also by their practical implications in the form of resulting

partiality, that is, the ways they benefit some parties while

neglecting the needs or concerns of others? Are there alternative

boundary judgments that might be just as adequate, and what would be their selectivity

and resulting partiality?

What ought to be my boundary judgments so that I can share

and defend them vis-à-vis those concerned? (Main setting:

individual reflection)

(2) Boundary discourse, that is, undertaking

a dialogical search for mutual understanding

and possible consensus through boundary-questioning deliberation:

Why do our opinions or validity claims differ? What different

boundary judgments make us see different "facts" and

"values"? What differences do they make in terms of

resulting partiality? What if we adopt one another's boundary judgments, how

do things then look to each of us? Can we agree

on differing boundary judgments; and if we cannot agree, can

we at least understand why we disagree and then limit our claims

accordingly? (Main setting: cooperative deliberation)

(3) Boundary challenge or contestation, that is, engaging

in controversial debate

through an emancipatory employment of boundary judgments:

What options are there for the boundary judgments assumed in

a claim? How can I make visible to others the ways in which

a claim depends on boundary judgments that have not been disclosed,

and how different can I make the claim look in the light of alternative

boundary judgments? How can I argue against an opponent's allegation

that I do not know enough to challenge him or her? Can I make

a cogent argument even though I am not an expert and indeed

may not be as knowledgeable as the opponent with respect to

the issue at hand? (Main setting: emancipatory challenge)

All

three types of boundary critique can help people understand

how relevant facts and values depend on the

choice of systems boundaries. The latters' optional character

– the availability of alternative ways to bound the reference

system in question, along with the unavailability of objective

justifications for chosen boundaries of concern – should become

clear and the normative presuppositions and conceivable consequences

of all options should be visible. The important point is that

people learn to identify the boundary judgments that inform

a claim so that

they can also question them systematically, by demonstrating

that there are options and how these options make the claim look

different. The

usual, unreflecting reliance on undisclosed and unquestioned

boundary assumptions – for instance, most characteristically,

in the experts' "facts" and "objective necessities"

– should thus give way to an openly and critically normative employment,

and ultimately to democratic legitimation, of boundary judgments

that affect third parties.

Emancipatory

boundary critique Lest this aim should depend

entirely on the willingness of experts and decision makers to

disclose their boundary judgments, the constructive, self-critical handling

of boundary judgments which is important in types 1 and 2 of

boundary critique is complemented in type 3 by their critical

employment

against those who are not willing to handle their boundary

judgments so self-critically. The emancipatory use of boundary

judgments – or shorter, emancipatory boundary critique

– aims to make visible the operation of power, deception, dogmatism

or other non-argumentative means behind rationality claims.

It accomplishes this purpose by creating a situation in which

a party's reliance on undisclosed or unquestioned boundary

judgments becomes apparent.

The

idea is that whenever a claim depends crucially on some boundary

judgments that are taken for granted rather than being disclosed

and systematically questioned, or which are even asserted dogmatically (e.g., with reference to superior expertise)

or consciously concealed (e.g., in connection with a hidden

agenda),

then the role of such non-argumentative motives and strategies

can be exposed by simply advancing alternative boundary judgments

and claiming their relevance, as well as by showing how the claim in question now looks different. The

other side is then forced to defend its boundary judgments but

is of course quite unable to prove "objectively" why they should be of superior

validity.

Experts

caught in such embarrassing situations tend to take refuge in

their advantage of knowledge and to suggest that a non-expert's

objections are "subjective" or "incompatible

with the facts," and in any case do not agree with "the

way professionals see it"; but that will do little

to establish the objective necessity of their own boundary judgments.

On the contrary, once it has become plain that defining the

system of concern (or any other reference system) is at bottom a subjective political act, those

experts

who insist on their superior qualification or objectivity with

regard to boundary judgments will only disqualify themselves.

The "deep symmetry" of which I have spoken is thus

brought to the surface and creates a situation of improved argumentative

equality, or what I have elsewhere described as a symmetry

of critical competence (Ulrich, 1993, p. 604f).

In

this way ordinary citizens may not only learn to see through

the appearance of objectivity and rationality behind which people

with an advantage of knowledge and power tend to conceal their

boundary judgments, they may also begin to understand that (and

why) this advantage is quite insufficient a basis for defining

the system of primary interest – along with its relevant environment

and the adequate context of responsible action – or for suppressing discussions on alternative

conceivable borders of concern. They are then able to shift

the burden of proof, as it were, and challenge the experts'

claims to rationality without needing to be experts themselves.

What

is more, this kind of emancipatory use of boundary judgments

represents an entirely rational and therefore cogent way of

argumentation. Following Kant's (1787, B767) concept of the

polemical employment of reason – a concept that I have

discussed elsewhere in detail (see Ulrich, 1983, pp. 301-310)

– I also call this type of argument "polemical," for

it is distinctive of a polemical argument as Kant understands

it that its critical

force and rationality do not depend on any positive validity

claim. Since it serves not a theoretical purpose of asserting

knowledge but rather an emancipatory purpose of exposing a dogmatic assertion of

knowledge, what matters is not that it

be able to establish a positive claim to theoretical truth or

normative rightness (or both) but only that nobody can prove

it wrong by virtue of an advantage of expertise. This is precisely

what an openly subjective advancement of alternative boundary

judgments achieves! Just as it cannot be proven true or right

or objectively necessary by theoretical means, it equally cannot be proven to be objectively

wrong. Thus citizens who use boundary judgments in this way

for merely

critical argumentation need not be afraid that they will immediately

be convicted of lacking expertise or competence. Because it

entails no theoretical or normative validity claim, no theoretical

or other kind of special knowledge

is required. This is why I believe that the concept of boundary

critique offers us a key to making accessible to citizens a new critical

competence. I know it sounds like squaring the circle,

but it seems to me that we have indeed identified here a new,

untapped source of civil competence.8)

Practicing

Boundary Critique The reader who has

followed me thus far will now want to know concretely how the

boundary judgments in question look like. Obviously the general

concept of boundary judgments needs to be operationalized so

that people can apply it, that is, can identify and discuss

boundaries of concern systematically.

The

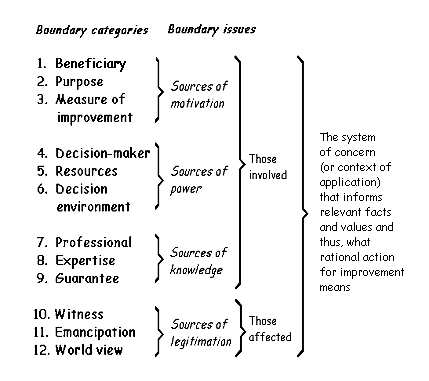

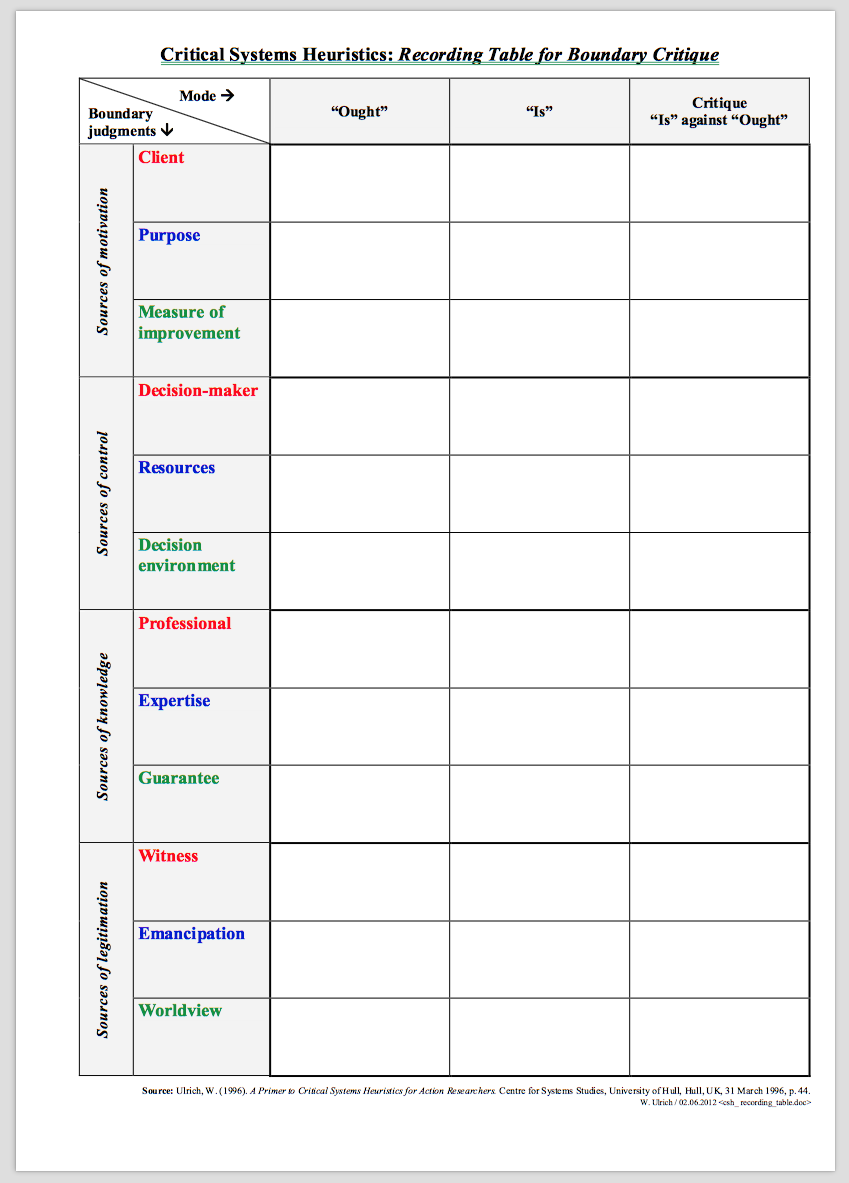

table of boundary categories With a view particularly

to the applied disciplines, as well as to everyday problem solving

and decision-making, critical systems heuristics (CSH) suggests twelve basic

boundary problems or so-called boundary categories (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Table

of boundary

categories

The selectivity of

practical claims is

traceable to four basic boundary issues: a claim's sources

of motivation, of power, of knowledge, and of legitimation.

Each of these four issues is in turn operationalized by means

of three boundary categories. The first refers to a type of

stakeholder, that is, a social role ascribed to people depending

on their specific way of being involved and/or affected; the

second to a role-specific stake, that is, an essential concern

of each group of stakeholders; and the third to a crucial stakeholding

issue, that is, a main difficulty that needs to be resolved so

as

to gain a clear understanding of the boundary issue in question.

There are thus twelve boundary categories, each of which requires

a boundary judgment in respect of both what is and what ought

to be case. Together these twenty-four boundary judgments define

an actual ("is") as compared to a desirable ("ought")

reference system for assessing a practical claim's meaning and

merits.

(Sources:

Ulrich, 1983, p. 258, and 2000, p. 256)

In

the terms of Kant's (1787) Critique of Pure Reason, which

provided a major source of inspiration for the development of

boundary critique (see Ulrich, 1983, chapters 3-5, pp. 175-314),

the twelve boundary

concepts represent categories of relative a priori

judgments. They are a priori in that they come logically

and temporally prior to the way we experience and evaluate so-called

"real-world" situations; they

are relative in that they are not prior to all possible

experience and evaluation in general (as Kant claims for his

a priori categories of pure theoretical and practical reason)

but only to the specific contexts of inquiry and action in which

practical questions arise (cf. Ulrich,

1983, pp. 188-193, esp. 191f). As explained above with the eternal

triangle, we cannot meaningfully discuss a practical question or

claim

in terms of relevant "'facts" and "values"

without assuming some boundary judgments by which we delimit the

assumed real-world context or situation to be improved (i.e.,

the

intended system of primary concern) along with its "environment" (i.e., the assumed decision-environment) and its "context of application" (i.e., the assumed context of responsible

action). The task of thinking through these issues of delimitation

can then be understood in terms of giving both empirical

and normative content to the twelve boundary categories (Fig. 4),

in ways that deal openly and systematically with the selectivity

involved.

Reflective practice cannot avoid this task; for whenever we advance

or rely on some observational or evaluative statements,

we have already – whether consciously or not – assumed

what is or should be the content of these categories.

Like Kant's (1787,

B106) categories of experience, which go back to Aristotle's

(1984) Organon, the boundary categories of critical heuristics

are arranged in four groups of three categories each. In Kant's

work, each group stood for an essential source of understanding

and unity in phenomenal experience, and consequently also for

a basic form or type of valid judgments about nature (the world

of phenomenal experience).9)

In

critical systems heuristics, each group stands for a source of human intentionality

or purposefulness that is essential for understanding the empirical

and normative selectivity of a practical proposition or claim. As

Fig. 4 shows, the first group asks for the sources of motivation

and corresponding ends that condition a claim; the second group,

for the available sources of power and corresponding

means and reach of control; the third, for the essential sources

of knowledge and corresponding forms of expertise; and the

fourth group, finally, for the required sources of legitimation

and corresponding forms of accountability.

Unlike Kant's categories, the critically-heuristic categories are derived from sociological

rather than metaphysical and logical considerations;10) they address the social actors or "stakeholders"

(a term that was not available in the late 1970s when critical

systems heuristics was first developed) whose

views and intentions determine what in a situation of concern

to them counts as relevant knowledge and proper practice:

- The first category of each group refers to a social role (or

type of stakeholder) that is or should be involved

in defining the reference system in question (i.e., a system

of concern S, or its relevant environment E, or the

context of responsible action A).

Example: the role

of "professional"

Corresponding boundary

question: Who is/is to be involved as professional

(e.g., researcher, designer, expert)?

- The second category of

each group addresses role-specific concerns (or

stakes) that

are or should be included.

Example: the need for

"expertise"

Corresponding boundary question:

What counts/should

count as relevant expertise?

- And

finally, the third category of each group relates to key problems (or

stakeholding issues) that are crucial

for understanding the previous two boundary judgments.

Example:

the inevitable lack of "guarantee" that reliance

on expertise and professional

guidance will indeed secure improvement.

Corresponding boundary question: What

are/should

be the assumed sources of guarantee that improvement

will effectively result, as distinguished from assumed

sources of guarantee that risk being false or deficient guarantors

of success?

Applying

the three types of boundary categories to each of the four basic boundary

issues of Fig. 4 yields a set of twelve kinds of boundary judgments that

together

define a claim's reference system, that is, the context that

matters when it comes to assessing the meaning, merits and defects

of a proposition (Ulrich, 2000, p. 251; Ulrich and Reynolds,

2010, p. 254). More precisely, each category prompts us

to reflect on what contextual assumptions are actually

taken to matter and what alternative assumptions might or should

ideally matter. Each of the twelve boundary categories

can thus be understood to give rise to two corresponding boundary

questions, the one asking for what are and the other

for what ought to be the boundary judgments at issue.

A

checklist of boundary questions From what we just

said, it follows that a useful way to introduce the boundary

categories is by means of a checklist of boundary questions.

The reference

system informing a specific claim can accordingly be understood

to be defined by the set of answers

given in a situation of concern to the twelve boundary questions of CSH:

Definition: The

reference

system informing a specific claim is defined by the set of answers

given in a situation to the twelve boundary questions of CSH.

As

I have recently introduced such a checklist in a previous Bimonthly

essay (Ulrich, 2017b), I present it here is a slightly

different form; however, its intent and content remain the same (Table 1).

Table

1: Checklist of boundary questions

The

boundary questions operationalize boundary critique as a systematic

process of questioning. The order of the questions may be chosen

freely, according to what appears particularly relevant or interesting

to ask for a start. Each boundary question has two parts; the

second part, beginning with "That is…," serves to define

the intent of the underlying boundary category. Each question should

be answered both in an “is” mode (What are the actual boundary

assumptions informing this claim?) and in an “ought” mode (What

should or would ideally be the reference system to be considered?).

Differing

“is” and “ought” answers point to unresolved boundary issues.

The aim is to uncover such issues and to explore options

for resolving them, so as to see a situation and related claims

in different ways, rather

than to find definitive answers. Even where "is" and

"ought" answers agree, it may be advisable to ask

how well-funded such a consensus is.

The aim is boundary testing,

not boundary fixing. It is therefore always a good idea to systematically

vary one's boundary judgments and see how different the

"facts" and "values" taken to be relevant

then look. In this way, systematic

iteration of boundary judgments can convey a sense of the

selectivity and resulting partiality of claims without presupposing a given basis

of judgment, that is, without an illusion of objectivity.

(Source:

adapted from Ulrich, 2000, p. 258,

and prior versions in 1987, p. 279f,

and 1993, p. 597)

|

Sources

of Motivation

(1)

Who is (ought to be) the beneficiary

(or client)? That is, whose interests are (should

be) served?

(2)

What is (ought to be) the purpose?

That is, what are (should be) the consequences?

(3)

What is (ought to be) the measure

of improvement

(or measure of success)? That is, what trade-offs

between conflicting purposes are (should be) built

into the way success is measured?

|

|

Sources

of Power

(4)

Who is (ought to be) the decision-maker?

That is, who is (should be) in a position to change

the measure of improvement?

(5)

What resources

are (ought to be) controlled by the decision-maker?

That is, what conditions of success can (should)

those involved control?

(6)

What conditions are (ought to be) part of the decision

environment?

That is, what conditions can (should) the decision-maker

not control (e.g., from the viewpoint of

those not involved)?

|

|

Sources

of Knowledge

(7)

Who is (ought to be) considered a professional

(or expert)? That is, who is (should be) involved

as an expert, e.g., as a researcher, designer or

consultant?

(8)

What kind of expertise

is (ought to be) consulted? That is, what counts

(should count) as relevant knowledge?

(9)

What or who is (ought to be) assumed to be the guarantor

of success? That is, where do (should) those

involved seek some guarantee that improvement will

be achieved (e.g., in consensus among experts, a

valid and relevant data basis, a scientific attitude

of objectivity, a moral stance of impartiality or

fairness, involvement of all stakeholders, consultation

of independent and impartial third parties, blind

peer review, crowd wisdom / crowd voting / crowd

sourcing, support by power-holders, etc., or are

they perhaps false guarantors)?

|

|

Sources

of Legitimation

(10)

Who is (ought to be) witness

to the interests of those affected but not involved?

That is, who argues (should argue) the case of those

stakeholders who cannot speak for themselves, including

future generations and non-human nature?

(11)

What secures (ought to secure) the emancipation

of those affected from the premises and promises

of those involved? That is, where does (should)

legitimacy lie?

(12)

What worldview

is (ought to be) determining? That is, what different

visions of “improvement” are (should be) considered,

and how are they (should they be) reconciled?

|

Introducing the boundary judgments in

this way offers three advantages. First, it allows formulating the boundary questions

so as to define the intent of each boundary category; in the

table above this is done by means of the "That is …" part

of every boundary question. Second, it allows formulating the

questions so that they explicitly call for both a descriptive ("is") mode

and a normative

("ought") mode of questioning, that is, for asking

both "What is currently the case?" and "What

should really be the case?" And third, it provides a systematic

order for examining boundary judgments and thus relieves the user

(especially beginners) from each time determining the best order for

using the boundary questions.

At

the same time, introducing the boundary issues as a checklist

of boundary questions may also involve some traps. In particular,

there is a danger that the boundary questions are misunderstood

to call for definitive answers, and moreover that the order

in which they are listed is followed mechanically. These and

a few other issues of good practice is what I propose to briefly

consider now. I'll begin with two possible misunderstandings

that would make boundary critique an unduly cumbersome process.

Boundary

critique: how to start Boundary critique depends

more on the quality of the reflective and discursive process

it inspires than on the completeness of the answers we give

to the boundary questions. In any case, a certain focus is always

recommendable with a view to keeping the effort manageable.

While the

idea obviously is that all of the boundary questions have critical significance for reflective

practice, not all may be of equal relevance or equally helpful

in each

application. Rather, the importance of the different boundary

questions tends to be situational. Further, the most important

thing in the process of boundary critique is that it actually

gets going and then, as interesting and relevant issues emerge,

fuels itself. It is a good idea, therefore, to vary the time

dedicated to the different questions, as well as the order in

which they are examined, according to such situational considerations.

It

is recommendable, then, to start with a few selected boundary

questions that make an obvious difference to how a problem or

situation is seen, and subsequently to follow up the further

boundary issues that emerge. Make

sure though that in the end, at least one question from each of the

four groups of boundary issues has been considered, as a way

to ensure that the concerns of all four stakeholder groups will

receive due attention.

The

reason why such a start – and the procedural economy it brings

– does not lead to an arbitrary result is that the boundary

questions are strongly interdependent. When we modify one of

the boundary judgments, all others are likely to change as well.

That is, the answers we give to any particular boundary question

is likely to influence the answers we subsequently give to all

other questions, and it may in fact compel us to revise previously

given answers to other questions. In short, in a thoroughly

handled process of boundary critique, the order in which we

consider the questions may be more or less efficient but should

not really determine the resulting understanding of the boundaries

of concern (i.e., of the reference system that matters). Due to

the strong interdependence of boundary judgments, users may

indeed feel free to start the process of boundary critique with

any of the boundary questions that they find particularly relevant

or interesting, if only they are then willing to pay

attention to the further boundary issues that their answers

raise.

Boundary

critique and the S-E-A-U scheme Equally important

with regard to procedural economy is a second basic consideration.

In view of our earlier discussion of the different types of

reference systems, some readers might wonder whether the boundary

questions have to be applied to each of the four basic reference

systems (S-E-A-U), so that effectively four rounds of boundary

critique would be required. They might accordingly worry about

the practicality of boundary critique. However, there is no

need for such worries. The

boundary questions have been formulated from the start so that together,

they cover all four basic reference systems. And, as we just

learned in the previous comment, due to their strong interdependence

they will do so even if not all the questions are unfolded with

equal detail. As a rule, it is thus not necessary to develop four different

sets of answers to properly identify and unfold the selectivity

of claims. A better idea is to carefully think of all four reference

systems, and of the main two types of delimitations involved

(i.e.,

A/U no less than S/E, cf. the discussion of this topic in Part

1), while unfolding each and any boundary question.

Another

argument against the need for (and wisdom of) four separate

rounds of boundary critique is that most real-world claims rely

on a set of considerations that are inspired by several of the

S-E-A-U perspectives. The four reference systems S-E-A-U are

therefore best understood as ideal-types that in practice we

hardly ever encounter in pure form. When we apply the twelve

boundary questions with a view to promoting rational practice

rather than considering them theoretically, we may thus expect

them to touch on all the issues intended by the four types of

reference systems; a circumstance that does not prevent us of

course from temporarily focusing on one type of reference system

so as to deal with specific issues as they may emerge in a process

of boundary critique.

As

a last consideration, the use of the boundary questions

not only in a descriptive ("is") but also in an openly

normative ("ought") mode equally helps boundary critique

avoid the trap of a one-sided focus on reference system S, which

would then need to be compensated as it were by separate rounds

of boundary critique from the perspectives of E and A. In a

well-understood process of boundary critique, examining the

boundary assumptions of a system or situation of interest S,

or of related claims to systemic or situational rationality,

quite naturally leads to the two crucial boundary problems of

delimiting the system of interest S from

its (decision-) environment E on the one hand and the context

of application (or of responsible action) A from the universe

U on the other hand, and thus to including the reference systems

E and A. It would be rather artificial indeed, if not plainly

impracticable, to assign these closely interdependent issues

to separate rounds of boundary critique.

Boundary

critique as a "process of unfolding" Boundary critique is often

misunderstood to be about boundary

setting. While it is correct that boundary critique should help

us remove uncertainty about boundary assumptions, such a removal

of uncertainty is not to remove boundary assumptions from the

agenda, in the sense that they would then require no further

consideration. The idea is not to check them off – get them

"done and dusted" as it were – but to make sure they

are and remain transparent to all the parties concerned, so

that their selectivity can be unfolded and challenged and alternative

assumptions can be examined. In short, the aim is boundary testing

rather than boundary setting or fixing: "How

different does the claim look if we change this or that boundary

judgment?"

Perhaps

the best way to describe this process of tracing the implications

of alternative boundary judgments is in terms of a process

of unfolding (Ulrich, 1983, whole Ch. 5). That which is

to be unfolded is of course the selectivity and resulting partiality

of boundary assumptions, in one word, their normative content.

As there is no natural end to this process, boundary assumptions

need to remain open to revision and it should become common

practice that all claims to relevant knowledge, rational action,

and resulting improvement are to be qualified with respect to

them. Such claims can then be limited accordingly, so that decisions

based on them can be taken without claiming too much.

Boundary

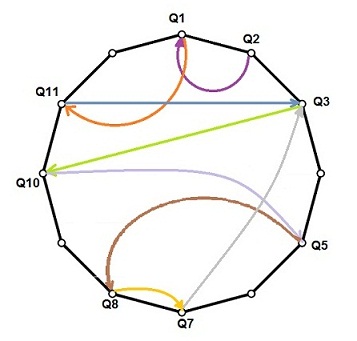

critique as an

iterative process We have seen that in the practice

of boundary critique, there is no need to adhere to any specific

order in which the boundary questions are unfolded. Users should feel free to start the process with any

question that looks particularly relevant or interesting to

begin with, and then to continue with whatever next question

may come up in the light of the considerations inspired by the

first question, and so on. Since all the boundary questions

are interdependent, in the sense that the answers to any one

will influence the answers to all others, it does not really

matter with which question one begins. Boundary critique should

be understood as an

iterative process that can and should follow the logic

of a boundary discussion as it unfolds rather than

any strict linear order (Fig. 5).

Copyleft  2017 W. Ulrich 2017 W. Ulrich

Fig. 5: Boundary

critique as iterative process

The process

of unfolding the boundary questions can be handled as a process

of free iteration

Personally I have often

found it useful to follow the sequence marked as an example

in Fig. 5. So I will usually start with question (2) before turning to

question (1), which then may lead to question (11) and on to

questions (3), (10), or conversely to question (10) followed

by questions (3) and (11), and so on. In the "is" mode, the logic of reflection

is then something like this:

(Q2)

The

purpose question:

What

is the main purpose

(the big idea)?

(Q1)

The

client question:

Who

stands to benefit

(the beneficiaries)?

(Q11)

The

emancipatory question:

What

requirements of accountability and participation are assumed

to

free those affected from the premises and promises of those

involved

(the sources of legitimacy)?

(Q3)

The

measure-of-improvement question:

What

is the standard of improvement

for handling conflicting

expectations

(the trade-offs assumed in defining success)?

(Q10)

The

witness question:

Who

may have to bear negative consequences without benefiting

and/or

having a say, and who speaks on their behalf

(those affected

but not involved)?

(And

so on)

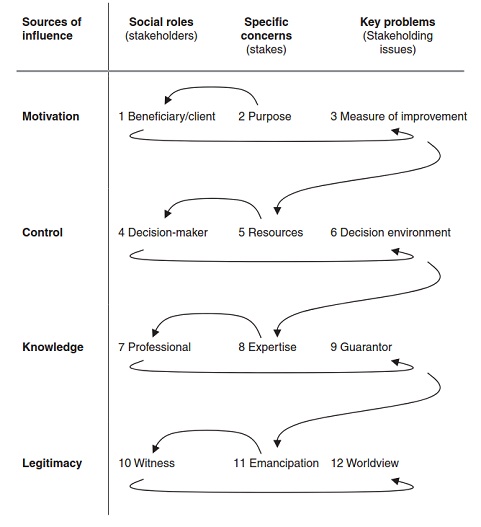

Perhaps

easier to remember for beginners is another standard sequence

that I have found useful particularly for teaching purposes,

first suggested by Reynolds (2007) (Fig. 6):

Fig. 6: A

standard sequence for unfolding the boundary categories

For

beginners it may be useful to follow this easily remembered

standard sequence of boundary critique (Sources: Ulrich and

Reynolds, 2010, p. 259;

adapted from Reynolds 2007,

p. 106)

But

again, the order in which the boundary questions

are considered may really be left to the way a discussion develops

or a facilitator suggests. It is also possible at all times

to go back to an earlier-discussed boundary question, if subsequent

considerations call for its revision. This is what it means

to say that boundary critique is an

iterative process. It should be clear then that the point of the checklist

is not to impose a rigid order but rather, to facilitate a meaningful

choice of the next question one might want to consider at any stage of

a boundary reflection or discourse.

A

recording table for boundary critique Given the iterative nature of

the process of unfolding the boundary categories, it makes sense

to keep a record of the ideas as they come up. Here is a recording table

to this end that can be increased to A4 format or letter size

for printing out as a worksheet (see Table 2).

Table

2: Recording table for boundary critique

(Source:

Ulrich, 1996, p. 44)

Click on figure to open it

Copyleft  1996 W. Ulrich 1996 W. Ulrich

Combined

table Instead of the answers we can enter the boundary questions themselves

in each field of the above table. In effect this combines the

table of boundary categories with the checklist of boundary

question into a single table, although such economy of representation

comes at the

expense of dropping the explanatory "That is …"

clause of the full list. Even so, this combined table may provide

a useful aide-mémoire of the issues to be addressed

in boundary critique (see Table 3).

Whether

(especially as a beginner in boundary critique) one prefers

to rely on the full checklist of boundary questions or on the

combined table, or rather (as an experienced practitioner)

finds it sufficient to have the table of boundary categories

at hand, the aim remains the same: it is to get a

sense of the boundary judgments that are actually operative

in a claim, as distinguished from alternative

boundary judgments that might seem more appropriate.

|

|

|

|

|

Actual and ideal mapping A

basic tool that can drive the process of unfolding the implications

of boundary assumptions for the parties concerned, and thus

to identify problematic as distinguished from more appropriate

boundary judgments, is by systematically examining them from

both an "is" (actual mapping) and "ought"

(ideal mapping) perspective. Combining these two modes of boundary

questioning helps to identify unresolved conflicts of views

and values as to what "the problem" and its "solution"

is. It allows for a certain rigor not only in dealing

with questions of "fact" but also in dealing with

questions of "value," in that it makes it apparent

at all times that

due to the underlying boundary judgments, both types of statements

are always selective and accordingly can be better understood

by asking for their normative along with their empirical content.

In this way it becomes transparent that there are always options

for defining relevant facts and values, for the simple reason

that there are always options for defining appropriate boundary

judgments. It also

helps in better understanding how different (groups of) people can arrive at

different notions of what are "the" relevant facts

and values. It can make us more tolerant for the differing positions

of others and thus provide a better basis for mutual understanding.

Clarifying

design ideals or visions for improvement Ideal

mapping also lends itself to a

more specific, independent use, namely, as a tool for

the creative exploration of design ideals or options for the future

along the lines of Ackoff's (1974, pp. 26 and 29f; 1981, pp. 104ff) concept

of idealized design and Churchman's

(1979, p. 82f) similar concept of ideal

planning; my own version of it in CSH is "ideal

mapping" as distinguished from "actual mapping"

of reference systems (cf. the two case studies in Critical

Heuristics, Ulrich, 1983, pp. 377-414).

Towards

a new rigor in evaluation research Further,

the combination of actual mapping with a previous round of ideal

mapping lends itself to a specific application in evaluation

research and other types of research or practice that aim at

systematic valuation based on research or vice-versa, at research

based on a clear value basis. By beginning with ideal mapping,

one can first clarify the value basis for the subsequent effort

of research or professional intervention. Boundary critique thus

allows a new rigor in the task of value clarification and

at the same time

provides a basis for evaluation without any illusion of objectivity.

"When the optional character of underpinning boundary

judgments becomes obvious, the mask of objectivity slips."

(Ulrich, 2000, p. 259) The discipline of evaluation research,

which since its emergence in the 1960s and 1970s has been understood

and practiced mainly as an empirical-analytic science, might

thus finally find ways to deal systematically with its value

content, namely, in the form of pluralist evaluation

grounded in, and combined with, systematic efforts of boundary

critique (for some emerging proposals in this direction, see,

e.g., Gates, 2017; Reynolds, 2014; and Schwandt, 2017).

When

are boundary judgments appropriate? I mentioned

above that since there is no such thing as definitive, objectively

right boundary judgments, the more modest aim of boundary critique

can only be to improve the basis for choosing "appropriate"

boundary judgments – more appropriate, that is, than the ones

who may presently be taken for granted. But what

does "appropriate" mean if there

are no definitively "right" boundary judgments? A basic test that I use to

assess an alternative

boundary judgment as compared to a current one is by asking

myself whether I could better argue it to be conducive

to improvement, for example, because it embodies a more comprehensive

or long-term perspective or is acceptable to a larger group

of people concerned. Similarly, I identify

appropriate boundary judgments by considering whether I could publicly share them with all the parties concerned,

as a touchstone for their not representing a merely or mainly

self-serving interest or even some hidden agenda.

The

quest for appropriate boundary judgments is never a quick and

trivial matter. As I have emphasized, boundary critique (as the name suggests)

is not primarily a tool for boundary fixing but for boundary testing,

that is, for surfacing the boundary judgments on which a claim

depends and thus for being able to see the claim in the light

of alternative boundary judgments. Since there are no objectively superior

boundary judgments, boundary critique

cannot be expected to bring forth quick, simple and obvious

answers. This is why we need it in the first place – because

no such answers exist. Further, boundary critique can also be

demanding because each boundary question has the potential

to inspire reflections or deliberations that really go the

heart of a problem situation and compel us to think and argue

more carefully and deeply than we usually do about what in a

specific situation should count as relevant knowledge, rational

action, and adequate improvement. The sequence of boundary questions

by which I earlier illustrated a useful way to start the process

of boundary critique (Q2 – Q1 – Q10– Q3) provides an example;

I find it useful as it makes me think early on in the process

about core issues such as what is a proposal's "big idea"

(Q2) and what kind of trade-offs between conflicting aims or

expectations should flow into the assumed measure of improvement

(Q10).

That such questions are

difficult to answer does not mean they are irrelevant or impractical,

quite the contrary – they are difficult because they

are deeply relevant, in the double sense

of being crucial for effective pragmatic action and for

relevant critique.

If pragmatic performance is measured by the aim of securing

effective action towards genuine and defensible forms of

improvement – doing things right and doing the right

thing – then boundary critique is certainly a powerful pragmatic

tool.

The

best way to get a personal sense of this pragmatic performance

is by experiencing it, that is, by trying for oneself

and beginning to apply the boundary questions in practical situations,

and be it only by listening to people's arguments and trying

to identify their underlying boundary judgments. Once we have

understood the concept of boundary judgments, we can learn as

much about them on the bus or in a street café as in

the lecture room and in research practice. A skilled practitioner

of boundary critique will make it a personal habit to

be attentive to the boundary judgments people use, and also

to ask what options there might be for them. People's ways to think and talk about matters of concern to

them is the best training ground there is for boundary reflection

and discourse. Reading case studies may also help

a bit, but it cannot replace personal trying and experience.11)

Too

abstract and demanding for ordinary citizens and managers? Readers who have not been exposed to critical heuristics

before may think that all this is quite nice but so abstract

and complex that it is difficult to see how ordinary citizens

and managers could apply it. Are we not dealing here with fundamental philosophical

difficulties of the systems idea and of the theory of knowledge

and rationality in general, for example, concerning the meaning

of practical reason and the unavailability

of comprehensiveness and objectivity?

Precisely! If boundary judgments are indeed as

fundamental to everyday speech

and argumentation as I argue, it must be possible to explain their

nature and also their emancipatory

implications to ordinary citizens. It is true, we are dealing

with a concept of systems-theoretical origin here, and systems theory may

well be beyond the interest and understanding of a majority

of

citizens. But at the same time, the concept of boundary judgments is so elementary

that grasping it can hardly be reserved to systems theorists.

Boundary judgments are not an esoteric invention of mine, they

are an all-pervasive everyday reality; so why should it be

impossible in principle to demonstrate their importance by means

of everyday language and everyday examples?

Indeed, as

I have tried to show,

we do not really need systems language to grasp the idea that the practical meaning of a proposition –

the difference

it makes in practice – depends on how we bound the system of

reference. Instead we may talk of the relevant

"situation," or of the definition of the "problem," of

the "context that matters,"

and so on. Similarly, instead of using the abstract notion of

boundary judgments, we can speak of "borders of concern," of

the

reach of responsibility, and so on. I can't see why ordinary people should not be able to understand that when

they differ with others, this is

not necessarily so because all others got their facts and values

wrong or are stupid but rather, because their borders of concern

are different.

The

everyday observation that people are "at cross-purposes"

gets a new and relevant meaning here; it means that people's

boundary judgments differ, not only with respect to

boundary category No. 2 (Q2) but also to other boundary issues. It is then quite normal that different

facts and values matter to them, a circumstance that need not

mean people are unreasonable or lack good will. On the contrary,

wouldn't it be surprising if despite differing boundary judgments,

people would arrive at the same observations and concerns?

Yet

it

is so easy – easier than questioning one's boundary judgments

or those of others – to assume that people lack understanding or good

will (or both) if they don't agree with us, although chances

are it is simply because their boundary judgments are different.

Unfortunately, too many people are still not aware of the role that

boundary judgments

play, in everyday observations and valuations no less than in

academic and professional discourses. If only they were aware of the concept,

it could make mutual understanding and

tolerance so much easier and thereby could also provide a basis

for rational deliberation and cooperation.

Conclusion:

Systems Thinking, Management, and Citizenship A

proper concept of good management education today should probably

equip future managers to assume more responsibility than is now

usual for the longer-term consequences and side-effects

of their actions. How managers

conceive of managerial problems, and what solutions they perceive

as "rational" solutions, has a lot to do with their boundary

judgments. To take two examples that look more obvious than

they are from a methodological point of view, the call for ecologically

sustainable forms of industrial production increasingly require managers

to include within their assumed contexts of rational

action the concerns of future generations

and non-human nature; but then, to make this rationally possibly,

they need new tools of cost accounting and financial reporting

in which costs imposed on those affected but not involved matter.

Accounting has as much to do with boundary judgments as

have environmentally sustainable forms of production and business

ethics, yet boundary critique is not as yet a systematic part

of it.

To

be sure, we cannot expect managers to be

altruists in charge of everyone and everything and thereby to neglect their core business of making business.

But we should indeed expect them to be competent in what they do as

managers, and such competence certainly involves systematic

reflection on the boundary judgments that inform

their decisions and consequent efforts, together with

concerned citizens, to handle these boundary judgments in transparent and responsible

ways.

The

day may not be so far away when citizens begin to pay more attention than at

present to the boundary judgments behind managerial decisions

that affect them. They will then want to challenge these decisions

both argumentatively and through their decisions as consumers.

So managers should have every interest in learning early on

how to deal carefully with managerial

boundary judgments. It cannot be too early for management education

to begin to prepare future managers now and to form their understanding

of competent management accordingly. In this new understanding

of management, competent management has something to do with

competent citizenship; far from being in opposition to it, it

will depend on it.

I do not want to be misunderstood. The point is not to renounce professionalism

or diminish its role but to deepen our understanding of it.

In spite of the increasingly

important role that I would like to assign to competent citizenship,

and that is, to ordinary citizens, I am convinced that management

will remain a key function in society, one that requires well-prepared

people and should be fulfilled as professionally as possible.

I am thus not arguing against professionalism, only against our contemporary

notion of professional competence, especially in the field of

management. This present notion is a rather superficial one,

it seems to me, in that it ignores the "deep symmetry" of professional

and non-professional judgments of which I have spoken. Contemporary

management theories and fads (Jackson, 1995), due to their ignoring the role

of boundary judgments, suffer not only from a defect of

modesty and self-reflection but also from a lack of

relevance and depth for management education and practice.

Academically trained managers engaged

in responsible positions could tell us about that!12)

For the same reason, present-day notions of professionalism still

tend to put non-professional people in a situation of incompetence,

even when they are supposed to serve them (Ulrich, 2000).

They thereby miss important sources of motivation, as well

as of knowledge and legitimation, for successful practice. Along

with this deficit come the manifold gaps between theory and

practice, science and politics, and "facts" and "values"

(or expertise and ethics), of which we are all more or less aware

in this epoch of "organized irresponsibility" (Beck,

1992; 1995) but for which we have no methodological answers

in the form of clear theory and practicable tools. Perhaps

the principle of boundary critique and its underlying theoretical

and philosophical framework of critical systems heuristics (CSH)

can contribute a small piece to the difficult puzzle we face,

by helping us to deal a bit better with these deficits.

The

time has come, I think, to start preparing today's management students for their

future jobs by training them not only to master technical management

know-how but also to handle such know-how truly professionally

– that is, as I see it, by taking the critical turn towards a reflective kind of competence

that would be informed by the concept of boundary critique.

A complementary

vision that could motivate and sustain such a critically reflective

stance might be competent citizenship, according to the

double motto:

Citizenship

without some sense of competence is empty;

competence without

some sense of citizenship is blind.

If we educate future

managers

to associate their professional competence with competent citizenship,

they will not only gain a deeper understanding of their own

societal role but will also be prepared to give ordinary citizens

a competent role to play in the societal definition and legitimation

of good and professional managerial decisions. I cannot think of a more meaningful vision for

a truly systemic concept of rational management than that of

management as competent citizenship.

I don't know whether you, the reader, agree; but if you do,

you will not need to give young people the kind of advice that

the German satirist Karl Kraus is reported to have given to

a student who wanted to study business ethics and which I here

adapt a little to the critical study of systems management:

"You want to study critical systems thinking in management?

Then decide yourself for the one or the other!"

This

surely cannot be the answer we offer contemporary management

students. The time is ripe for promoting forms of systems thinking

in management and professionalism that make a difference. The

case for boundary critique is strong indeed.

Let us train future

managers in systems thinking as if citizens mattered.

|

|

|

|

|

References (for Parts 1 and 2)

Achterkamp,

M.C, and Vos, J.F.J. (2007). Critically identifying stakeholders:

evaluating boundary critique as a vehicle for stakeholder

identification. Systems Research and Beahvioral Science,

24, No. 1, pp. 3-14.

Aristotle

(1984). Categories. In The Complete Works of Aristotle, The Revised

Oxford Translation, Vol. 1, ed. by J. Barnes, Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press, pp. 3-24.

Barbalet,

J.M. (1988). Citizenship: Rights, Struggle and Class Inequality.

Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Barber,

B.R. (1998). A Place for Us: How to Make Society Civil and

Democracy Strong. New York: Hill and Wang.

Beck,

U. (1992). Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London,

UK, and Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage (German orig. of 1986: "Risikogesellschaft:

Auf dem Weg in eine andere Moderne").

Beck,

U. (1995). Ecological Politics in an Age of Risk. Cambridge,

UK: Polity Press (German orig. of 1988: "Gegengifte: Die

organisierte Unverantwortlichkeit").

Bendix,

R. (1964). Transformation of Western European societies since

the eighteenth century. In R. Bendix, Nation-Building and

Citizenship: Studies of Our Changing Social Order, New York;

Wiley. Enlarged, Edition, Berkeley, CA: University of California

Press, 1977. Republished London: Taylor & Francis/ Transaction

Publishers, 1996, and Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis,/ Routledge,

2017, pp. 66-174.

Bochenski,

I.M., and Menne, A. (1965). Grundriss der Logistik. 3rd

edn. Paderborn, Germany: Ferdinand Schöningh (French orig.

1949, German 1954, Engl. 1959).

Bochenski,

J.M. (1959). A Precis of Mathematical Logic. Dordrecht,

The Netherlands: D. Reidel.

Bryk,

A. (ed.) (1983). Stakeholder-Based Evaluation: New Directions

for Program Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carr,

S., and Levidow, L. (2000). Exploring the links between science,

risk, uncertainty and ethics in regulatory controversies about

genetically modified crops. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental

Ethics, 12, No. 1, pp. 29-39.

Cohen,

J. (1983). Class and Civil Society: The Limits of Marxian

Critical Theory. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts

Press.

Coombes,

P., Smit, M., and MacDonald, G. (2016). Resolving boundary conditions

in economic analysis of distributed solutions for water cycle

management. Australian Journal of Water Resources, 20,