|

|

|

Systems

get in the way.

(John

Gall, How Systems Work

and Especially How They Fail,

1978, p. 127)

The

occasion: farewell

to Ulrich's Bimonthly

There

was a time when the Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Company famously

cited the horsepower of their engines as "sufficient,"

which I always found an elegant and so unmistakably British

understatement for saying "more than needed." Perhaps

in academia, where (it seems to me, at times) the number of

publications now is everything and their quality almost nothing,

we might do well to adopt a similar convention, say, by describing

everything over 100 as "sufficient." But of course,

this risks being a therapy for the symptom rather than for the

problem; which is that quantity (if not overproduction) appears

to go at the expense of quality. It might become necessary to limit the number of

publications that everyone is entitled to publish or, at least,

to get academic credit

for, so that people would have a real incentive to focus on

quality rather than quantity. Be that as it may, I have come

to the conclusion that the number of Bimonthly essays

that I have written is

"sufficient." Consequently, I'll stop writing more

of them. Motto: "Enough is enough."

I

do not promise to stop writing altogether, though. Just to do it in

a freer, and slower, rhythm. I'll become a

Slow Professor

(Berg and Seeber, 2016; cf. the short reviews by Farr, 2016, and

Hanson, 2017; also see Honore, 2005, the pioneer of the "slow"

movement, and Boulous Walker, 2017).

My focus will no longer be on writing new essays but on (slowly) completing those series of

essays which are not complete as yet, such as the series dedicated to

the role of general ideas in Western and Eastern thought, titled

"The Rational,

the Moral, and the General"; the "What is Good Practice?"

series; then the "Reflections on Critical

Pragmatism"; and finally, based on all the others, the "Reflections

on Reflective Practice" series.

Further, as the Bimonthly will no longer be able to serve

its function of giving my readers an easy access to some of

my latest writings, I will eventually embark on an extension

and partial restructuring of my website in terms of thematic streams,

that is, sections of the site that will more or less converge

with the main themes I dealt with in the Bimonthly, among

them the series of essays just mentioned. I

do not promise to stop writing altogether, though. Just to do it in

a freer, and slower, rhythm. I'll become a

Slow Professor

(Berg and Seeber, 2016; cf. the short reviews by Farr, 2016, and

Hanson, 2017; also see Honore, 2005, the pioneer of the "slow"

movement, and Boulous Walker, 2017).

My focus will no longer be on writing new essays but on (slowly) completing those series of

essays which are not complete as yet, such as the series dedicated to

the role of general ideas in Western and Eastern thought, titled

"The Rational,

the Moral, and the General"; the "What is Good Practice?"

series; then the "Reflections on Critical

Pragmatism"; and finally, based on all the others, the "Reflections

on Reflective Practice" series.

Further, as the Bimonthly will no longer be able to serve

its function of giving my readers an easy access to some of

my latest writings, I will eventually embark on an extension

and partial restructuring of my website in terms of thematic streams,

that is, sections of the site that will more or less converge

with the main themes I dealt with in the Bimonthly, among

them the series of essays just mentioned.

In

this last regular issue of Ulrich's Bimonthly, then,

I would like to

do something a bit special. Beginning with a glance back, I would

like to reflect on some key considerations and motives that

led me to conceive of "boundary critique" as an indispensable

(though neglected) idea of systems thinking and hence, as a

methodological core principle of my attempt to imagine what I then called a critical

systems approach (Ulrich, 1983, p. 25 and passim) to

social planning and other fields of applied science and professional

practice. To help me

step back in time to the late 1970s and early 1980s, when I

set out to develop what is now known as critical systems heuristics (CSH),

I will adopt a dialogical format and think of the kind of answers that I might have

given then (and still could give today) in an interview about

my work. The result is a fictitious interview with myself about

the reasoning that gave rise to what has been the focus of my

work ever since, the role and importance of "boundary judgments"

in all matters practical.

This will lead us quite naturally

to the second topic of the present essay, which focuses on the

nature of the boundary judgments in question and their adequate

handling. I will try and give an overview of some major tools

and guidelines that are available today for practicing boundary

critique, especially as proposed by CSH. For this purpose as

well, I will benefit of the interview setting.

Third and last,

I will turn to the vision of a knowledge democracy that has been motivating my work and which, as I believe,

remains a meaningful aim for future work. I take this opportunity

to publish an edited version of the "Erskine Prestige Lecture" that I was

allowed to present to the staff and students of the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand,

on 26 May 1999. At the time, I

was asked to bring along and make available a written version

of my lecture, which subsequently was circulated within

the University. However, as my appointment ended shortly after,

I did not find the time to edit it as planned and in consequence it was

never published. The present "Farewell" Bimonthly provides a decent occasion, I think, for finally

publishing it. To keep this first

publication of my Erskine Lecture as close as possible to the

original, and the last Bimonthly issue as short as one might

expect and wish, at least optically, I'll offer the Lecture as

a downloadable appendix that comes in the same form and layout

in which it was originally circulated, except for the edits

of course.

Some passages have been expanded or are new, and some of the

references have been updated; but on the whole, the paper remains

fairly close to the original lecture.

AN

INTERVIEW WITH MYSELF

Any author is easy if you can catch the center

of his vision.

(William James, American philosopher

of pragmatism, 1977, p. 44)

Q1:

What basic idea led you to develop critical systems heuristics

(CSH)?

The

German social theorist and philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1985, p. 173),

asked about his basic motive for grounding critical social theory

in a Theory of Communicative Action (Habermas, 1984/1987), once remarked that at bottom his version of a critical theory of

society explicates one central intuition, namely, that

reasonable speech contains an intrinsic telos (finality)

of mutual understanding. Whenever we communicate, we

anticipate

that the people we talk to can understand what we want to tell

them, so that there is a chance to reach mutual understanding. This anticipation,

Habermas believes, is necessarily built into speech as without

it, it makes little sense to communicate.

Similarly, if

you ask me what led me to conceive of a critical systems approach, I

might explain it as an attempt to work out a central intuition,

namely, that there is an intrinsic telos in systems

thinking that to this day has not received adequate attention: whenever

we try to think systemically, we cannot help but anticipate

that the way we delimit a system of interest is adequate

for understanding and improving the situation or issue in question.

Systems thinking implies an intrinsic need for understanding

systems boundaries or, as I prefer to say so as to make their

judgmental nature clear, the boundary judgments

that inform our systems concepts. Epistemologically speaking,

these boundary assumptions stand for justification break-offs,

that is, points at which our

chains of argumentation break off, both on the side of presuppositions

or conditions and on the side of effects or implications;

normatively speaking, they stand for assumed borders of concern.

Both the meaning and the validity of

propositions depend on them. Without an effort to understand these unavoidable

limitations of argumentation and commitment, we cannot expect systems thinking (or

for that, any other kind of systematic inquiry and practice)

to be conducive

to clear and relevant thought. Indeed, as I noted in the Primer

(Ulrich, 1996, p. 17), we do not need the systems concept at all if we

are not interested in handling systems boundaries critically.

But if we are, as I added in the Erskine Lecture (Ulrich, 1999/2018, p. 7), then systems thinking becomes a form of critique. Therein I see the fundamental

critical kernel of systems thinking.

This, then, is the central intuition that I link to the idea

of systems thinking. I owe it to a period of two years in my life, the years

1978-79, that I

dedicated almost exclusively to the study of Kant's (esp. 1786, 1787) critical philosophy

as applied to both the theoretical-empirical and the practical-normative

use of reason, that is, to the search for knowledge (guiding

ideal: the idea of science) and for rational action (the

moral idea). Kant woke me up from my previous, pre-critical understanding of the

scientific idea as well as of the moral idea and, linked to

both, the systems idea. As it slowly dawned on me, all three

ideas imply a quest for comprehensiveness, that is, for

some kind of holistic (e.g., Churchman,

1968, 1982) or interconnected (e.g., Vester, 2007) thought.

It is one of the most fundamental principles of reason to take

into account everything that is conceivably relevant to an issue

or argument. So reason has no choice but to try and consider

all the conditions and implications of its own conjectures.

In principle, there is no natural or conceptual limit to this

endeavor in that we can always expand the boundaries of what

we take into account; in practice though, it is always

limited and thus deficient. While comprehensiveness is a meaningful quest, it is not a meaningful

claim, a claim that would be critically tenable.1)

After Kant, I could no longer understand the systems idea in the same way as before. It had become to me what Kant would have called a critical idea of reason, an idea that compels us to reflect on the limited and conditioned nature of all

our understanding and reasoning. The

limiting factor at issue is the inevitability of boundary judgments –

judgments as to what constitutes the relevant "whole system,"

the total situation or context to be considered – in all our

cognition, that is, in our ways of seeing, thinking, communicating and doing things.

At the same time, however, the systems idea must itself remain forever

problematic to our understanding, as we can neither give it a definitive empirical content nor ultimately justify

the normative content of any claims to systems rationality.

Its use, even for critical purposes, is not immune to the problem

it helps us diagnose, the inevitable selectivity of all

our claims and justifications due to underlying boundary judgments. The

only tenable use of the systems idea, then, is a self-reflective

and self-limiting employment, as against any

holistic pretensions. This is the sort of thoughts which, although

still rather unclear to me then, sent me onto what Kant famously

called the

critical path – the only path still open after leaving behind us the dogmatic

(i.e., uncritical) and the skeptical (i.e., nihilistic) paths

(Kant, 1787, B884). I now

refer to it as the critical turn of systems thinking

and, linked to it, of all our notions of knowledge, rational

action, professional or any other form of competence, applied science and expertise, improvement, and even

morality (compare, for example, my discussion of research competence,

critically turned, in Ulrich, 2001a and 2017b-c).

Q2:

Given this basic motive of a critical turn in systems thinking, how did you seek

to translate it into a systematic framework for reflective practice?

From

what we've discussed so far it follows that the central methodological

aim of critical systems heuristics

(CSH) is to support systematic processes of boundary critique,

that is, a transparent and critical handling of boundary

judgments. When I was setting out to develop CSH, in the years

1976-80 during

my stay at the University of California, Berkeley, the field of systems

theory and systems thinking (including the so-called systems methodologies)

had not begun to cultivate any kind of reflective practice with respect

to boundary judgments. Nor had any other field of inquiry

and practice of which I would have been aware. (But of course

it was the systems theorists whom one might have expected in

the first place to take care of the problem of boundary judgments.)

Hence, some new tool of thought needed to be developed.

It was clear to me that such a new approach would not be a stand-alone

approach but rather should aim to complement and enrich existing

practices of inquiry in all fields, systems research / systems

design as well as other applied

disciplines, many of which have by now been influenced by systems

thinking or in any case face similar issues of delimiting the

reach of valid findings and conclusions.

I

should emphasize in this context that "boundary judgments"

are not an invention of mine, nor a specific problem of systems

theory. Rather, they have been there all along, in virtually

all fields of research and professional practice of which I

can think.

But apparently few people saw them or wanted to see them; and

those who did failed to come up with a systematic framework

for handling them. Nor are they a problem caused by the systems approach

– the systems idea is only the messenger of the bad news (Ulrich,

1981). Ignoring

the bad news or accusing the messenger of being its cause does

not help. The

problem of boundary judgments is pervasive and accordingly is

in need of a systematic critical handling. So it was obvious that whatever framework would

eventually be developed to support such a critical

handling, it was indeed to support and complement, not replace, existing tools

and practices of inquiry. In this self-limiting sense, CSH was not going

to establish or justify any positive claims to knowledge and

rationality in its fields of application but would only serve to limit and

qualify such claims,

as grounded in existing, specialized disciplines and increasingly

also in the emerging fields of inter- and transdisciplinary

research and practice.

Even

with a view to this limited and self-limiting end, it

was clear that a careful theoretical

grounding, both philosophical and methodological,

was required; philosophical,

that is, in terms of both epistemology (theory of knowledge)

and practical philosophy (theory of rational practice, including

theory of moral reasoning). Only

thus could the framework be expected to reach academics in different

fields and to provide a clear and convincing explanation of

its systematic intent: of clarifying what rational practice

could still mean in the face of the unavoidability of boundary

judgments, that is, of inevitable selectivity as to what counts

as relevant knowledge and as rational argumentation. This is how

I would describe the systematic intent of CSH from a theoretical

point of view..

Just

as obviously, practicability was essential if the approach was to be broadly accepted. Whatever theoretical

grounding of a "critical solution" to the problem

of boundary judgments would emerge, it would have to prove its

value in the practice of applied research and professional intervention,

as well as in everyday problem solving and decision-making. A

majority of people should be able to understand and apply it,

not only well-trained professionals or even just a small group of

philosophers or theorists. Accordingly it needed to be translated into heuristic concepts

that would be accessible to "ordinary"

researchers, professionals, decision-makers, and citizens regardless

of whatever specialized knowledge and expertise they had concerning

the situation or issue

at hand. It's the heuristic concepts

in question, not the people who want to apply them, which need

to be theoretically well-grounded; whereby "well-grounded"

includes the qualification of being formulated so that a majority of non-specialists

can understand and use them. (Remember that even academics and experts do

most of the time belong to the non-specialists, namely, as soon

as the expertise required lies outside of their field of special competence). Although it

is a common

misunderstanding that "heuristic" concepts are a kind

of theory-free concepts of low argumentative value, this is

not so in my understanding of a critical systems approach, in which

heuristic concepts are to serve as critical

ideas in support of self-reflective practice. "Heuristics is epistemology brought down

to earth." (Ulrich, 1983, p. 41)

The

name I chose for such a solution to the problem of boundary

judgments, "critical systems heuristics" (CSH),

stands for three basic aims.

CSH should:

1. support

critical reflection and discourse with respect

to the inevitable selectivity, due to the problem of boundary

judgments, of all claims to knowledge,

rationality, and improvement;

2. embody

a critical turn of systems thinking that would be

accessible to

a majority of people without any specialized knowledge;

and

3. amount

to a flexible and widely applicable framework

of critical heuristics of social practice rather than of

critical

theory of society.

Heuristic

concepts as I understand them can help us ask relevant questions

and examine the assumptions and implications of different conceivable

answers, but they do not serve to justify any particular answers

as the only correct ones. The proper use of heuristic concepts

is moreover a self-reflective use. The critically-heuristic

nature of such a framework of systemic thinking does not, however, dispense it from

being grounded in a careful and explicit theoretical foundation.

In

sum, the systematic intent of CSH was to work out the philosophical and methodological implications of the central intuition we

were talking about at the outset, and then to translate these

implications into critically-heuristic tools for reflective

practice. Accordingly, the two crucial questions to be clarified

were:

- Inasmuch

as our claims to knowledge, to rationality, competence,

and improvement, are conditioned by boundary judgments,

how should

we understand the meaning and validity of such claims? (aim:

theoretical grounding; basic thrust: qualifying claims

in terms of assumed boundary judgments).

- Can

we develop tools that a majority of people might use to

systematically examine the resulting selectivity of claims,

that is, to identify the boundary judgments at work

and unfold their practical implications? (aim: securing

practicability; basic thrust: supporting reflective

practice with respect to boundary judgments and their implications

for all those concerned).

CSH was to be my attempt to clarify the meaning

of this "systematically."

Q3:

Can you hint at some of the key concepts to which this

attempt gave rise and which belong to its intended "pragmatic"

side?

As

said above, the methodological core idea of CSH is to support

systematic processes of boundary critique. The question

is, what kind of conceptual tools does CSH propose to this end?

Or, to put the same question differently, how does CSH try to

operationalize boundary critique? Let me try to hint

at some of the key concepts to this end. I say "hint"

as this is not the occasion for a systematic introduction; at

best I can give a bit more space to two or three of them while

treating the others in a rather cursory fashion. I shall, however, give references to sources where readers can find

fuller accounts.

Settings

for boundary critique: To begin with, CSH

distinguishes between three basic settings and corresponding

uses of boundary critique:

(1)

Self-reflective boundary questioning:

"What

are my (our, their) boundary judgments?"

Aim:

cultivating

reflective practice as to boundary judgments that inform current

views and values and related claims to relevant knowledge, rational

action, and resulting improvement.

Typical questions:

What boundary judgments

do I

/we /they presuppose? What is their selectivity

as measured by the facts and values they exclude from consideration?

How partial are they in the sense of benefiting some parties while

neglecting the needs or concerns of others (i.e., resulting

partiality)? Are there options for less selective and partial

boundary assumptions?

What alternative boundary judgments would I prefer (e.g., so that I could share

and defend them vis-à-vis those concerned)? (Main setting:

individual reflection)

(2)

Dialogical boundary

questioning:

"Can

we agree on our boundary judgments?"

Aim:

reaching mutual understanding on boundary judgments.

Typical questions: What different

boundary judgments make us see different "facts" and

"values"? What differences do they make in terms of

resulting partiality? What if we adopt one another's boundary judgments, how

do things then look to each of us? Can we agree

on differing boundary judgments; and if we cannot agree, can

we at least understand why we disagree and then limit our claims

accordingly?

(3)

Controversial boundary questioning:

"Don't

you claim too much?"

Aim: rational critique

of claims that rely on boundary judgments taken for granted

by others.

Typical questions: Can I make visible to others the undisclosed

boundary judgments on which a claim depends? Can I with equal

right advance some alternative boundary judgments? How different does

a disputed claim then look? How can I defend such emancipatory

boundary questioning against an opponent's allegation

that I do not know enough to challenge him or her?

(see

Ulrich, 2000, p. 15; 2017e, p. 10f)

All

three types of boundary critique can help people understand

how what they see as relevant facts and values depends on the

choice of systems boundaries. Their shared aim is to uncover the

optional character of all boundary judgments. On this basis,

mutual respect and understanding can grow even where views and

values continue to differ. People no longer need to assume that

the other

parties argue dishonestly or irrationally or in any case got

their "facts" and "values" wrong. That may

be so at times; but much more often they simply rely on

different boundary judgments, and nobody has a claim to own

the

only correct ones. Cultivating the habit of boundary reflection

(the first use of boundary critique) and providing opportunities

for systematic boundary discourse (the second and third

uses) can get people accustomed to such considerations and

thereby, over time, will enable them to develop a new critical

competence.

Boundary

categories, boundary questions, and other tools: Basic

to all three uses of boundary critique is that

people learn to systematically identify the boundary judgments that inform

a claim. On this basis people can then question their own boundary

judgments as well as those of others. This can happen by tracing their empirical and normative

selectivity with respect to the "facts" and "values"

they include as against those they exclude or marginalize, as

well as by then unfolding the resulting partiality of

the claim informed by these boundary judgments, that is, its

implications for the different parties concerned. People will thus also learn to demonstrate

to others what options there may be for some boundary

judgments they consider crucial, and how these options may make a specific claim

– its selectivity and partiality, that is – look

different.

Systematic

identification and unfolding of boundary judgments can be facilitated

by a number of simple conceptual tools such as a table of boundary

categories; a checklist of boundary questions; a standard sequence

for raising them; and a form for recording observations or conjectures

generated by boundary critique. In principle, once people have

understood the idea of boundary critique, I would encourage

them to feel free and address any boundary assumptions that

they find particularly important for understanding

a specific situation, in whatever terms they find useful.

However, in the practice of boundary critique it is often useful

to have a basic typology of boundary judgments at hand,

so that the focus can be entirely on the situation and not on

first finding out what types of boundaries might need to be

considered. Especially beginners might be lost in the latter

case.

CSH

supplies such tools in the form of twelve

boundary categories, structured into four groups of thee, and twelve corresponding boundary questions

that are to be asked both in a descriptive (what is the case?)

and in a normative mode (what ought to be the case?), thus yielding

24 questions overall. A standard

sequence and a recording table are also available (the latter in

particular offering itself for digitalization). These tools

are easily found in my writings, so I need not present them here

in any detail (see, e.g., Ulrich, 1983; 1987; 1996; 2000; 2017e;

Ulrich and Reynolds, 2010). Suffice it to say that they have

proven themselves to be applicable and relevant in many domains

of research and practice, as well as for didactic purposes.

Where users find this is not so, and especially also with increasing

experience in boundary critique, they should feel free to adapt

these tools or the ways they use them, including their language,

to their specific needs; what matters is not the terms but the

underlying concepts and their critical intent.

Emancipatory

boundary critique: Since boundary critique will in practice

often give rise to disagreements about boundary judgments or to attempts at concealing

or imposing them, it is vital for a framework of boundary critique

that it expands and operationalizes the notion of a critical

handling of boundary judgments by a practicable model of cogent

critical argumentation against boundary judgments that are

not handled so critically. This is the essential concern of

the third of the three above-mentioned settings and uses of

boundary critique, the controversial case. I refer to it as

emancipatory boundary critique (Ulrich,

e.g., 1999/2018, p. 16; 2000, pp. 257-260; 2001c, p. 95f;

2006, p. 78f; 2017e, pp. 7-9 and 11-13). It is such an

important concept that it merits a somewhat more detailed discussion.

The

methodological key concept by means of which CSH operationalizes

the idea of emancipatory boundary critique is the polemical

employment of boundary judgments (Ulrich, 1983, pp. 301-310;

1987, p. 281f; 1993, pp. 599-603; 1996, p. 41f). It

takes up a rather neglected concept from Kant's critical philosophy,

the "polemical employment of reason" (Kant, 1787,

B766-797). By a polemical argument Kant means an argument that

aims not to establish any claim to objectivity (or, as we would

rather say today, to empirical truth or normative rightness)

but only to demonstrate the dogmatic, underargued nature of

an assertion. It achieves this aim by relying

on a counter-assertion that nobody can prove to be objectively

false or impossible, as little as anyone can prove it to be

objectively correct or even necessary. As it claims and

requires no theoretical validity, its relevance and proper use

do not depend on its prior positive justification and

thus, on any theoretical or specialized knowledge that only

experts could have. Its only use is a critical one.

A

polemical argument, then, has only critical validity; but as such it

must be relevant (i.e., make a difference) and cogent (i.e.,

rationally arguable). Kant's notion of the polemical employment

of reason has thus nothing to do with "polemics" in

today's popular sense of the term; it aims at the cause, not the

person, and it must be logically compelling. It is an entirely

rational, because anti-dogmatic, kind of argumentation, so long as it is used

for critical purposes only.

Boundary

judgments perfectly lend themselves to such a critical use,

although Kant does not of course mention them as an application

of his concept of the polemical

employment of reason. Since they do not admit of theoretical justification

or falsification, nobody can prove them to be objectively false,

as little as objectively right or necessary. Ordinary citizens

can thus use them to show the dogmatic character of propositions

that do not lay open their underlying boundary judgments. Taking

an example from the domain of energy policy, the extent to which

we take future generations

to belong to the beneficiary (e.g., should it be the next two or the next thousand

generations?) is essential for deciding how

economically competitive, environmentally friendly, safe and

morally arguable renewable energy paths are as compared to fossil

fuels or nuclear power. The longer the time horizon, the better

renewable energy performs and the more problematic the other

options become. The beneficiary question obviously makes an essential

difference here, and the critical concerns that go with it can indeed

be

rationally argued in terms of foreseeable and well-known environmental

effects, costs, and safety issues. No special knowledge is required

that would not be available to a majority of ordinary citizens.

When it comes to such crucial boundary judgments, the "objective

necessities" to which many an expert likes to refer (not

surprisingly so, as experts still have a near-monopoly in identifying

and defining them) crumble and their mask

of objectivity slips. As soon

as people begin to recognize and question underpinning boundary judgments,

new ways of seeing things become available that previously were dogmatically

excluded or underrated.

What is more, ordinary citizens can advance alternative boundary

judgments or question those of the experts without needing to fear that they

will immediately be convicted of lacking the expertise required. Since boundary judgments do not involve

a claim to theoretical

justification but express subjective and value-laden borders

of concern, nobody can prove them objectively wrong or impossible; the

question is only how different they make a disputed claim look. Indeed it is not even necessary to conceal or deny

their personal, merely subjective character; they can be introduced

in overt subjectivity and for the only purpose of putting those

who take their own boundary judgments for granted in a position

in which it becomes obvious that they argue dogmatically.

It becomes then clear that experts who still present their findings

and conclusions as "objective necessities" move on

slippery ground. Citizens can thus demonstrate three essential

points:

(a) that

an expert's propositions and recommendations depend on underlying

boundary judgments for which there are options;

(b) that the expert's theoretical competence is insufficient to

justify his or her boundary judgments or to falsify those of

the critic; and

(c) that experts, inasmuch as they claim the objective necessity

of their professional findings and conclusions without qualifying

them in terms of the underlying boundary judgments, argue dogmatically

and thereby disqualify themselves (Ulrich, 1987, p. 282).

Emancipatory

boundary critique is not, however,

a cheap argumentative weapon that merely disregards the importance

and value of special expertise and thus could be said to give the

uninformed and uneducated an unfair advantage; for it is effective only against

those who do not handle their own boundary assumptions overtly

and critically. Experts who properly qualify their claims have

nothing to fear. Conversely, ordinary citizens lose the

argumentative advantage of emancipatory boundary critique – of

arguing "from the safe seat of the critic," as Kant

(1787, B775) puts it – as soon as they forget its merely critical

validity and start to assert the superiority or even unique validity

of their own boundary judgments.

The

polemical use of boundary judgments is always on the side of

those who cultivate a reflective handling of their boundary

judgments. It thus provides an effective

and fair methodological basis for boundary

critique. It shifts the burden of proof from those who argue carefully

and limit their claims, whether as concerned citizens

or as professionals and decision-makers,

to those who don't and claim too much. No more, no less. In this sense it entails a qualified shift of the burden of proof

that is both fair and rational. Given that it does not depend

on any special knowledge that would be beyond the reach of ordinary

people, yet is still widely unknown to a majority of people,

I see in it an emancipatory potential that remains

largely untapped today. I'll say a little more on this

potential in a moment, when I'd like to point to a personal

vision that might inspire future work on the idea and uses of

boundary critique, I mean the idea that the contemporary "knowledge society"

might develop toward a "knowledge democracy,"

a term I borrow from Gaventa (1991). First, however, I would like to hint at two, three more key

concepts of CSH, concepts I consider more basic.

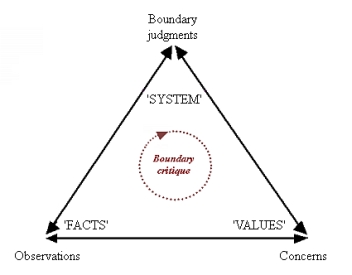

Systemic triangulation: Common

to all uses of boundary critique, including its emancipatory

employment, is an idea that I find very helpful for explaining

how boundary critique works, especially also for didactic purposes.

I call it the eternal triangle of

boundary critique. It says that three types of interdependent judgments are

unavoidably involved in all thought applied to real-word issues and situations:

- "FACTS"

– relevant observations or factual judgments;

- "VALUES"

– relevant evaluations or value judgments; and

- "SYSTEM(S)"

– relevant boundary

judgments or reference systems

(see

Fig. 1).

Fig.

1. The "eternal triangle" of boundary critique:

Argumentation

tasks in applied research and expertise

(Source:

Ulrich, 2012c, p. 11; earlier versions 2000, p. 252,

and 2003, p. 334)

The

three corners of the eternal triangle stand for the argumentative

tasks that inevitable come up with the three mentioned types

of judgments.

In a triangle we cannot modify any of the three angles (in this

case, arguments) without

affecting at least one of the other two. The

triangle reminds us to examine the ways each argumentative task

depends

on the other two and is likely to change with them. The result

is a circular movement of thought, of exploring the

interdependencies in question, which is indeed the basic point

of boundary

critique.

The

basic point, of course, is that both judgments of fact

(relevant observations) and value judgments (relevant evaluations) depend on boundary judgments

(relevant reference systems). In addition, the eternal triangle

also explains the often asserted but rarely well-understood

interdependence of factual and normative judgments: they both

are conditioned by the ways we delimit the relevant situation

or issue. Consistent judgments of fact (relevant observations)

and value judgments (relevant evaluations) share the same boundary

judgments as to the situation to be considered (relevant reference

systems). Consequently we cannot change the former without adapting

(or at least, checking) the latter. Conversely, when our concerns and corresponding value considerations change,

it is to be expected that new facts come into the picture, which

in turn may prompt new considerations as to how the

relevant situation may need to be redefined,

and so on (see, e.g., Ulrich, 2000, p. 252f; 2003, p. 334;

2017a, pp. 6-8; 2017e, pp. 5-7).

This

understanding of boundary critique leads to a conceptual tool to which I refer as systemic

triangulation, an extension of the better known conventional concept

of "triangulation" in the sciences. Conventional triangulation

suggests to analyze

and test theoretical hypotheses in the light of different, independent

data sets, as well as to interpret the data one relies upon in the light of

different theories. Systemic triangulation goes beyond

this conventional concept by also reviewing empirical and theoretical statements

(judgments of fact) in the light of different reference systems (boundary

judgments) as well as different normative assumptions (judgments

of value). Triangulation of validity claims thus becomes a systematic

process of thinking through the eternal triangle. By examining

each corner of the triangle in the light of the two other, we

can gain a deeper understanding of a claim's anatomy of selectivity

(see, e.g., Ulrich, 2003, p. 334; 2012c, pp.

11-13; 2017a, p. 8f).

Reference

systems for boundary critique: A specific, situational set

of boundary judgments defines what CSH calls a "reference

system," that is, a perspective for understanding the context

that is taken to matter for assessing and handling a situation

or issue of interest. But of course, there is not usually a

single set of boundary judgments that could be identified and

justified as amounting to the one best or definitive reference

system. It is the very core idea of boundary critique that any delimitation

of relevant contexts should always be kept fluent and should

in fact be systematically varied, rather than ever being taken

for granted. It's a way of keeping some critical distance, of

not becoming prisoners of our own boundary judgments. Although

in practice there always comes the moment in which we have to

pass from reflection and discourse to action, I would argue

that in our minds we should keep the option of alternative boundary

judgments open, lest we become blind to the selectivity of our

own assumptions and their consequences. "We have to maintain

the contradiction or else we allow ourselves to be overwhelmed

by the consistent." (Churchman, 1968, p. 229)

Boundary

critique can in this respect be understood as a form of multiple

perspectives thinking. With a view to maintaining multiple

perspectives in applied science and expertise, as well as in

everyday situations of practical thought, CSH distinguishes

between four basic types of reference systems:

- the

situation of concern or system of primary interest

(S);

- the

relevant environment or decision-environment

(E);

- the

context of application or of responsible action

(A); and

- the

total conceivable universe of discourse or of

potentially relevant circumstances (U).

Together,

these four reference systems embody four complementary rationality

perspectives for thinking through claims to relevant knowledge,

rational action, and resulting improvement, especially in complex

contexts of action. I also speak of the S-E-A-U formula of

boundary critique ("seau" is French for bucket

or pail, Fig. 2).

Fig.

2. The S-E-A-U imagery

of a complete set (or pail) of

reference systems for boundary critique

I

have offered an introduction to the concept of reference systems,

along with the four types of reference systems and their interpretation

as complementary rationality perspectives, in some recent Bimonthly

essays and thus may refer interested readers to these sources

(see Ulrich, 2017d, pp. 15-28, 2017e, pp. 2-4 and 19-21; and

2018, pp. 2-12 and 15f); specifically on the relation between

"situation" and "system," I also recommend

the short discussion in Ulrich and Reynolds (2010, pp. 251-253).

At present I just want to point out that there is no need, in

the face of such distinctions, for worrying that boundary critique

is overly complex. The previously mentioned checklist of twelve

questions covers all four perspectives, so that it is not usually

necessary to engage in separate rounds of boundary critique,

each with a focus on one of the four types of reference systems.

The S-E-A-U formula is not meant to complicate things but rather,

to facilitate a deeper understanding of what boundary critique

at bottom is all about – in one word: rationality

critique – as well as to support its practice when some

specific boundary questions are found particularly difficult

to answer; it may then help to examine the concerned boundary

judgments with an explicit and changing focus on each of the

four rationality perspectives.

Suffice

it here to note that

- a reference system is a whole

of circumstances or conditions selected from the (assumed) universe

that together

make up a context for assessing the meaning and validity of

a specific claim; whereas

- boundary judgments are the acts

of selection by which we delimit a specific reference system from

other conceivable reference systems and/or from the universe

(as an ultimate reference system for reflecting on the selectivity

of all other reference systems, an idea that in practice becomes

important especially in moral reasoning).

(Ulrich, 2017d,

p. 16)

The

three-level

concept of rational practice: This concept explains the

two-dimensional, Kantian concept of rationality that underpins

CSH. At the same time it seeks to operationalize it, by extending

Kant's (1786, 1787) two dimensions or "standpoints"

of reason – theoretical (-empirical) and practical (-normative)

reason – into a vertical model of three complementary levels

of systems rationalization. In the latest version, the three

levels now explicitly (rather than, as in previous versions,

only implicitly) refer to the three reference systems S, E, and

A, with U serving as an ultimate reference system for questioning

the delimitations of the other three (especially E and A). The

model embodies CSH's overall approach to systematic rationality

critique and as such serves as an important background concept

for practicing boundary critique (see Ulrich, 2018, pp. 12-27;

earlier accounts are found in 1988, pp. 146-159; 2001b,

p. 78-82; and 2012a, pp. 8-37, esp. 28-34). A complementary

concept is the principle of critical vertical integration

of rationality levels; interested readers will also

find it explained, as well as illustrated by two major examples,

in the mentioned sources (see esp. Ulrich, 2012a, pp. 34-44; 2018,

pp. 27-31).

So

much for some hints about the key concepts for which you asked

me. I think I should not get longer. Readers not yet

familiar with my work may wish to follow up some of these hints and

consult some of the literature references I've given.

Q4:

Now that you consider to become a "slow professor"

and to "slowly" reduce your amount of academic

writing, do you have any regrets as to unaccomplished aims or

remaining deficits of your work on CSH?

Certainly. I am thinking, for instance,

of the didactic challenge. I was so busy studying the philosophical

and methodological ("critically-heuristic") challenges

that I postponed an idea that I always had, namely, to test CSH in school classes

and, based on such experience and with their help, perhaps to

"translate" its terms into a language that would be

closer to young people. I am also thinking of the Irish program

for civil, social, and political education in secondary

schools (CSPE, 2016), which might be an exemplary kind of school

project for introducing CSH to young people and testing or developing

it with them. As a general stance, I propose that in

future, no child should leave school without having received

some training in boundary critique.

A similar

idea was to test CSH in adequate settings of adult education

and active citizenship, for example, as a tool to equip participants

of "planning cells" (Dienel, 1989 and 1991) or "citizens'

juries" (e.g., Crosby et al., 1986), "hybrid fora"

of scientists and citizens (e.g., Gibbons et al., 1994), stakeholder-based

evaluation (e.g., Bryk, 1983; Achterkamp and Vos, 2007; Gates,

2017), participatory

action research (e.g., Fals-Borda and Rahman; 1991; Whyte, 1991;

Reason, 1994; Ulrich, 1996) and other forms of participatory and community-based

research and citizen engagement.

Alas!

Nobody can do everything. I focused on work that I felt I was best

prepared for and which might not be done otherwise, I mean the

job of working out the basic philosophical and methodological

ideas that I had in mind. I am confident, however, that there are plenty of

people out there who are better qualified than I am to take

on the didactic task. I trust this will eventually happen.

More

theoretically speaking, I have not finished my attempts to translate

the ideas gained through my work on boundary critique into a

framework of what I'd like to call philosophy for professionals.

As I currently see it, such a framework would rest on two main

pillars that are still under construction. First and most importantly,

I see an urgent need for a renewal of

pragmatism toward what might justly be called critical pragmatism.

I have published a few articles in which I outline my ideas

on this (see, e.g., Ulrich, 2006 and 2007/2016). I have also begun

a Bimonthly series titled "Reflections on critical pragmatism"

with so far seven essays published between 2006 and 2016. I

may continue to add more such reflections. The other pillar

on which I have been working a bit is the methodological concept of

critical contextualism, which I think could support a

framework of critical pragmatism by helping both to ground it

epistemologically and to operationalize it with a view to systematic

practice. This idea was an important (although not the only)

motive for my Bimonthly series, equally uncompleted, on

"The rational, the moral, and the general: an exploration."

Another, related motive was

to explore the use of general

ideas as critically-heuristic ideas, that is, as standards

for boundary critique or, more accurately, as limiting concepts

towards which, as explained in these essays, critical contextualization

can orient itself.

A third motive has emerged while working on the series, the

opportunity it brought to explore entirely

new territory in the form of ancient Indian ideas, especially

of the Upanishadic tradition and, still in work, of the subsequent

tradition of Buddhist logic and philosophy. I do hope to complete

this work eventually.

Q5: What other

hopes do you associate with CSH for the future?

Similarly

to what I just said about school education, I could have imagined

to engage myself more in introducing boundary critique

to professionals. I believe that boundary critique is deeply

relevant to our contemporary notions of professional competence

(cf. Ulrich, 2000, 2001a; 2011a, b; 2012b) and professional ethics (cf. Ulrich, 2006; Schwandt, 2015). I did have a good number of opportunities though

to introduce CSH to practicing and future professionals from

a broad array of fields, and the experience was encouraging

throughout. Based on this experience, I tend to think that just

as no school kid should in future leave school without some

basic training in boundary critique, no professionals should

end their professional education or training without it. Those

who did not have such an opportunity in the past should have

it in the form of future continuing education offers. The Lugano

Summer School of Systems Design was such an offer that

I initiated in the past, aimed at practicing professionals as

well as doctoral or postdoctoral researchers.

Further,

I

have some hope that my work on boundary critique might contribute

in the future to a new kind of citizenship training,

aimed at conveying to citizens not only knowledge about politics and

citizen rights

but also the kind of competencies they need for exerting their

rights. How else can they become active citizens who know to argue their

concerns, even if at times it means to challenge those who claim to know better what is

good and right for them? I believe this need not remain a mere

utopia. The concept of the polemical employment

of boundary judgments, or of emancipatory boundary critique

as briefly introduced above, explains why and how ordinary

people can be prepared to meet experts on equal terms, at least

for critical purposes.

I

believe that people who have understood the idea of boundary

critique and perhaps have received some training in it, have

a realistic chance to help create a basic symmetry of critical

competence (Ulrich, 1993, pp. 604-606; 1999/2018, pp. 15-17;

2017c, p. 9f, 12) among all the parties involved and/or concerned

by a proposal or project, regardless of what their special skills

or deficits of expertise are (remember that even experts are

in most questions facing them non-experts). I refer to this

vision of a new, reformed kind of citizenship training as critically-heuristic training in citizenship

(e.g., Ulrich, 1983, pp. 397, 407; 1993, p. 608; 2000, p. 261).

Adult education and continuing professional education are related

fields of application for this vision.

My

ultimate vision though goes even further. I hope that based

on new concepts such as boundary critique, along with other

ongoing developments such as the forms of active citizenship

I have mentioned above, the contemporary knowledge society will

eventually become what we might call a knowledge democracy.

I

am not going to say more about this vision here, as it is

the topic of my so-far unpublished Erskine Prestige Lecture, appended

below. This was a lecture delivered to the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New

Zealand, in May 1999, and circulated internally thereafter but

not formally published. What better occasion could there be

for finally making it available to everyone than this "Farewell"

Bimonthly? Please find the PDF file below if you'd like to see

it.

Q6:

Let us end with a personal note. Could you share with us some favorite

quote, whether from the academic or the belletristic literature, that captures the spirit of your academic

work and life?

With

pleasure. One quote that currently is on my mind is the observation

that I cited in my last bimonthly essay, of January-February

2018, from Pirsig's Zen or the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance:

The

true system, the real system, is our present construction of

systematic thought itself, rationality itself.… There's so much

talk about the system. And so little understanding.

(Robert

M.

Pirsig, Zen or the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, 1975,

p. 94)

There

you have it all, the reason why we need to engage in "systems

thinking" and allow a majority of people to acquire some

critical competence in it. Pirsig's book was the first I read

after arriving at UC Berkeley, in March 1976, where I had come

to work with the pioneer of the "systems approach,"

C. West Churchman (cf. my appreciations in Ulrich, 2004 and

2012b), and to pursue what then was still a rather vague project

of developing a "critical systems approach" that would

be practicable for many people (1983,

p. 25). Along with Churchman's books, Pirsig's Zen

was indeed one of the books that got me started. So isn't it

quite fitting that at the end of this series of Bimonthly essays

I return to it, thanks to your question.

To

be sure, I would not do justice to the one major source that

really has shaped my personal "critical turn," Kant's

(1787) Critique of Pure Reason, without also offering

a quote from it. I had started to read the original German text before moving

to Berkeley, but there I started to read it in English, as I

would anyway need to cite it in English. I was fortunate enough

to select the outstanding translation of Norman Kemp Smith,

which for me has remained the best. It is such a fine translation,

faithful to the spirit as well as the language of Kant yet somehow

more modern and easier to read than the German original. My

understanding of Kant benefited enormously from this translation,

the more as I could always go back to the German text in cases

of difficulties or doubts as to how to interpret what I read.

It

was inevitable that sooner or later I would also find in the

book some passage that captured it all – the original intuition

and the ensuing inspiration and enduring hope that at least

a critical solution must be possible to the difficulties

and limitations of human reason in dealing with this messy world

of ours. Kant remains of ongoing importance, I

think, when it comes to understand the need for such a critical

solution and its basic requirements. As Kant would say, we have no choice but to

try and handle the key contemporary problems that mankind

is facing "with reason." I take Kant's word, therefore, that

as an alternative to dogmatism and nihilism, a critical

solution to the questions of reason might still be possible:

We

cannot, by complaining about the narrow limits of our reason,

escape

the responsibility of at least a critical solution

to the questions of reason.

(Immanuel

Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, 2nd edn.,

1787, B509;

my own transl.)2)

I

found this comment of Kant so important that I made it the guiding

motto of my book on Critical Heuristics (Ulrich, 1983,

p. 5). I have never regretted giving Kant's observation

this central place in my thinking;

it has always remained an inspiration to me. What better way

could there be to explain the idea of boundary critique?

You

also hinted at the possibility of a quote form the belletristic

literature, so as to end with a somewhat personal note. When

you said that, I immediately knew what it would be. It can only

be that most beautiful line from a poem by the French poet,

essayist, and philosopher, Paul Valéry, a line that I

never forgot since I first encountered it some forty years

ago and which, as I grow older, gains more and more meaning:

Le

vent se lève !… Il faut tenter de vivre !

("The

wind is rising !… Let us try to live !”)

(From

Paul Valéry's poem "Le cimetière marin,"

orig. published in 1920;

for a bilingual edn. see Collected

Works, Vol. 1, Poems, 1971, p. 220f)

____

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

PDF file

Note: This

essay's original title was "Toward a knowledge democracy: farewell to

Ulrich's Bimonthly." This title did not really capture

the intent of the essay, which is to offer a personal look back

at the origin and importance of "boundary critique"

in my work, whereas the concept of a "knowledge democracy"

is the subject of a separate article (my Erskine Lecture

of 1999) that is made available as an appendix to the present

essay. I have therefore changed the present essay's title to

"The idea of boundary critique," which is what

it is all about. The subtitle remains unchanged; it refers to

the fact that this

is the last issue of Ulrich's Bimonthly.

[12 Sep

2019]

|

|

|

|

References

Achterkamp,

M.C, and Vos, J.F.J. (2007). Critically identifying stakeholders:

evaluating boundary critique as a vehicle for stakeholder

identification. Systems Research and Behavioral Science,

24, No. 1, pp. 3-14.

Berg,

M., and Seeber, B.K. (2016). The Slow Professor: Challenging

the Culture of Speed in the Academy. Toronto, Canada: University

of Toronto Press.

Boice,

R. (1996). First-Order Principles for College Teachers: Ten

Basic Ways to Improve the Teaching Process. Bolton, MA:

Anker.

Boulous

Walker, M. (2017). Slow Philosophy:

Reading Against the Institution. London and New York: Bloomsbury

Academic.

Bryk,

A. (ed.) (1983). Stakeholder-Based Evaluation: New Directions

for Program Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Churchman,

C.W. (1968). The Systems Approach. New York: Dell (rev.

and updated edn., 1979).

Churchman,

C.W. (1982). An appreciation of Edgar Arthur Singer, Jr. In

C.W. Churchman, ed., Thought and Wisdom. Seaside, CA: Intersystems,

pp. 116-135.

Crosby,

N., Kelly, J.M., Schaefer, P. (1986). Citizens panels: a new

approach to citizen participation. Public Administration

Review, 46, No. 2, pp. 170-178.

CSPE

(2016). Civil, social and political education. Wikipedia

entry (stub) about the Civic, Social and Political Education

(CSPE) program, a compulsory subject of secondary education in

Ireland, last updated 8 Nov 2016 (orig. 5 Oct 2008), last accessed

15 May 2018, complemented here with two additional links to

relevant material.

[HTML]

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Civic,_Social_and_Political_Education

[HTML]

https://www.pdst.ie/sites/

[HTML]

https://www.actonline.ie

Dienel,

P.C. (1989). Contributing to social decision methodology: citizen

reports on technological projects. In Ch. Vlek and G. Cvetkovich,

eds., Social Decision Methodology for Technological Projects,

Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer, pp. 133-151.

Dienel.

P.C. (1991). Die Planungszelle: Eine Alternative zur Establishment-Demokratie.

Opladen, Germany: Westdeutscher Verlag (orig. 1977).

Fals-Borda,

O., and Rahman, M.A. (eds.) (1991). Action and Knowledge:

Breaking the Monopoly with Participative Action Research.

New York: Apex Press, and London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Farr,

M. (2016). The slow professor. University Affairs / Affaires

Universitaires, 29 March.

[HTML]

https://www.universityaffairs.ca/features/feature-article/the-slow-professor/

Gall,

J. (1978). Systemantics: How Systems Work and Especially

How They Fail. Pb. edn. New York: Pocket Books / Simon &

Schuster (orig. New York: Quadrangle / The New York Times, 1977).

Gates,

E.F. (2017). Toward valuing with critical systems heuristics.

American Journal of Evaluation, 39, 2018, issue

assignment and pagination not yet available. Preliminary online

publication 21 July 2017.

[DOI]

https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214017703703

Gaventa, John (1991). Toward a knowledge democracy: Viewpoints on

participatory research in North America. In O. Fals-Borda and M.A.

Rahman (eds.), Action and Knowledge:

Breaking the Monopoly with Participatory Action-Research. New York: Apex

Press, and London: Intermediate Technology Publications, pp. 120-131.

Gibbons,

M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., and

Trow, M. (1994). The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics

of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London:

Sage.

Habermas,

J. (1984/87). The Theory of Communicative Action. Vol. 1: Reason

and the Rationalization of Society; Vol. 2: The

Critique of Functionalist Reason. Cambridge, UK: Polity

Press, 1984 (Vol. 1) and 1987 (Vol. 2).

Habermas,

J. (1985) Dialektik der Rationalisierung, in J. Habermas (ed.),

Die

Neue Unübersichtlichkeit, Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp,

pp. 167-212.

Orig. published as "Dialektik der Rationalisierung: Jürgen

Habermas im Gespräch mit Axel Honneth, Eberhard Knödler-Bonte und

Arno Widmann," in Aesthetik und Kommunikation, No. 45/46,

1981. Engl. transl.:"The dialectics of rationalization: an

interview with Jurgen Habermas," Telos, 49, Fall Issue, 1981;

reprinted in P. Dews (ed.),

Autonomy & Solidarity: Interviews with Jurgen

Habermas, London: Verso, 1992, pp. 95-130.

Hanson,

L. (2017). The slow professor: Berg and Seeber deliver academic freedom lecture.

QUFA Voices, Your Queen’s University Faculty Association

Newsletter, 12, Number 5 (February 2017, Issue 67).

[HTML]

https://qufa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/67-QUFA-Voices-Feb-2017.pdf

Honore,

C. (2005). In

Praise of

Slowness: Challenging the Cult of Speed. New York:

Harper Collins.

James,

W. (1977). Hegel and his method. Lecture III, in W. James, A Pluralistic

Universe, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[HTML] https://www.fullbooks.com/A-Pluralistic-Universe1.html

Kant,

I. (1786). Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. 2nd ed. (1st ed. 1785). Transl. by H.J. Paton. New York:

Harper Torchbooks, 1964.

Kant,

I. (1787). Critique of Pure Reason. 2nd ed. (1st ed. 1781).

Transl. by N.K.

Smith. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1965 (orig. London and New

York: Macmillan 1929).

Pirsig,

R.M. (1975). Zen or the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.

New York: Bantam Books (orig. New York: Williams Marrow, 1974).

Reason,

P. (1994). Participation in Human Inquiry. London: Sage.

Schwandt,

T.A. (2015). Reconstructing professional ethics and responsibility:

implications of critical systems thinking. Evaluation, 21,

No. 4, pp. 462-466.

Ulrich,

W. (1981). On blaming the messenger for the bad news.

Reply to Bryer's comments. Omega,

The International

Journal of Management Science, 9, No. 1, 1981, pp. 7.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(81)90060-8 (restricted

access)

[HTML]

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0305048381900608

(restricted access)

Ulrich,

W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New

Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland, and

Stuttgart, Germany: Paul Haupt. Pb. reprint edn.,

Chichester, UK, and New York: Wiley, 1994 (same pagination).

Ulrich,

W. (1987). Critical heuristics of social systems design. European

Journal of Operational Research, 31, No. 3, pp. 276-283. Reprinted in M.C. Jackson, P.A. Keys and S.A. Cropper, eds.,

Operational Research and the Social Sciences, New York:

Plenum Press, 1989, pp. 79-87, and in R.L. Flood and M.C. Jackson,

eds., Critical Systems Thinking: Directed Readings, Chichester,

UK, and New York: Wiley, 1991, pp. 103-115.

[HTML] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/03772217/31/3

(restricted access)

Ulrich,

W. (1988). Systems thinking, systems practice, and practical

philosophy: a program of research. Systems Practice, 1,

No. 2, pp. 137-163. Reprinted in R.L. Flood and M.C. Jackson,

eds., Critical Systems Thinking: Directed Readings, Chichester,

UK, and New York: Wiley, 1991, pp. 245-268.

Ulrich,

W. (1993). Some difficulties of ecological thinking,

considered from a critical systems perspective: a plea for critical holism. Systems

Practice, 6, No. 6, pp. 583-611.

Ulrich,

W. (1996). A Primer to Critical Systems Heuristics for Action

Researchers. Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies, University of Hull,

31 March 1996.

Ulrich, W. (1999/2018).

Systems thinking as if people mattered: toward a knowledge democracy. Erkine Prestige Lecture, University of

Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 26 May 1999, ed. version of 1 May 2018 (first published version).

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1999_2018_erskine_lecture.pdf

Ulrich, W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil

society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective

Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713693151

(restricted access)

[PDF]

https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2000a.pdf

(prepublication version)

Ulrich, W. (2001a). The quest for competence in

systemic research and practice. Systems Research and Behavioral

Science, 18, No. 1, pp. 3-28.

[DOI] https://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sres.366

(restricted access)

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001a.pdf

(prepublication version, open access)

Ulrich, W. (2001b). A philosophical staircase for information systems definition,

design, and development (A discursive approach to reflective

practice in ISD, Part 1). Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 3, No. 3,

pp. 55-84.

[HTML]

https://aisel.aisnet.org/jitta/vol3/iss3/9/

(restricted

access)

[PDF]

https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001b.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2001c). Critically systemic discourse (A discursive approach

to reflective practice in ISD, Part 2). Journal of Information

Technology Theory and Application, 3, No. 3, pp. 85-106.

[HTML]

https://aisel.aisnet.org/jitta/vol3/iss3/10/

(restricted access)

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001c.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2003). Beyond methodology choice: critical systems thinking

as critically systemic discourse. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 54, No. 4, pp. 325-342.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601518

(restricted access)

Ulrich, W. (2004).

Obituary: C. West Churchman, 1913-2004. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 55, No. 11, pp. 1123-1129.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601825

(restricted access).

Ulrich,

W. (2006). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional

and business ethics. Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business

Ethics, Vol. 1, ed. by L Zsolnai. Oxford, UK, and Bern,

Switzerland: Peter Lang, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich,

W. (2007/2016). Philosophy for

professionals: towards critical pragmatism. Journal of the

Operational Research Society, 58, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1109-1113.

Rev. postpubl. version in Ulrich's Bimonthly, March-April

2016 (Reflections on Critical Pragmatism, Part 7).

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602336

(orig. version, (restricted acctess)

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2016.html

(rev. postpubli. version)

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2016.pdf

(rev. postpubl. version)

Ulrich,

W. (2011a). What

is good professional practice? Part 1: Introduction. Ulrich's Bimonthly, March-April 2011

(21 March 2011).

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2011.html

[PDF]

https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2011.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2011b). What

is good professional practice? Part 2: The quest for practical

reason. Ulrich's Bimonthly, May-June 2011

(20 May 2011).

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2011.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_may2011.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2012a). What

is good professional practice? Part 3: The quest for rational action. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, May-June 2012

(1 May 2012).

[HTML]https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2012.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_may2012.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2012b). Operational

research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective.

Part 1: OR as applied systems thinking. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 63, No. 9, pp. 1228-1247.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jors.2011.141

(restricted access)

[PDF]

https://orsociety.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1057/jors.2011.141#.XX9pka35zYU

(restricted access)

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_july2016.html

(post-publ. version, open access)

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2012d_prepub.pdf

(prepubl.

version)

Ulrich,

W. (2012c). Operational

research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective.

Part 2: OR as argumentative practice. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 63, No. 9, pp. 1307-1322.

[DOI]

https://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jors.2011.145

(restricted access)

[PDF] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1057/jors.2011.145

(restricted access) [HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2016.html

(post-publ. version, open access)

[PDF]

https://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2012e_prepub.pdf

(prepubl.

version)

Ulrich,

W. (2017a). The concept of

systemic triangulation: its intent and imagery. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, March-April 2017.

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2017.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2017.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2017b). If systems thinking is the answer, what is the

question? Discussions on

research competence (Part 1/2). Ulrich's Bimonthy, May-June 2017.

[HTML]

https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_may2017.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_may2017.pdf

(integral version Parts 1+2)

Ulrich,

W. (2017c). If systems thinking is the answer, what is the

question? Discussions on

research competence (Part 2/2). Ulrich's Bimonthy, July-August 2017.

[HTML]

https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_july2017.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_july2017.pdf

(integral version Parts 1+2)

Ulrich,

W. (2017d). Systems thinking as if people mattered. Part 1:

A plea for boundary critique. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, September-October 2017.

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2017.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_september2017.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2017e). Systems thinking as if people mattered. Part 2:

Practicing boundary critique. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, November-December 2017.

[HTML] https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2017.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_november2017.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2018). Reference

systems for boundary critique: A postscript to «Systems thinking as if people mattered».

Ulrich's

Bimonthly, January-February 2018 (25 March 2018).

[HTML]

https://wulrich.com/bimonthly_january2018.html

[PDF] https://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_january2018.pdf

Ulrich,

W., and Reynolds, M. (2010). Critical systems heuristics. In

M. Reynolds and S. Holwell, eds., Systems Approaches to

Managing Change: A Practical Guide, London: Springer, in

association with The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, pp. 243-292.

[PDF] https://www.springerlink.com/content/q0m0167621j10072/

(restricted access)

[PDF] https://oro.open.ac.uk/21299/

(open access)

Valéry,

P. (1971). Collected Works of Paul Valéry, Vol. 1,

Poems. Bilingual edn., transl. by David Paul. With notes

and commentaries by D. Paul and J.R. Lawler. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press. The poem "Le cimetière

marin / The graveyard by the sea" is found on pp. 212-221.

Vester, F. (2007). The Art of Interconnected Thinking: Tools and Concepts

for a New Approach to Tackling Complexity. Munich, Germany: MCB Verlag

(German orig.: Die Kunst vernetzt zu denken, Stuttgart, Germany, Deutsche

Verlags-Anstalt 1999).

Whyte,

W.F. (ed.) (1991). Participatory Action Research. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage.

|