|

|

<<

Continued from Part 1/2

What

Ought to Count as Knowledge?

Research is usually undertaken to increase

knowledge. A typical dictionary definition explains that research

is "to establish facts and reach new conclusions"

(Concise Oxford Dictionary of Current English). This

is not a bad definition. Counter to the frequent, often tacit identification

of research with empirical research, the Oxford definition tells

us that research requires two kinds of competencies:

- observational

skills to "establish facts," and

- argumentative

skills to "reach new conclusions."

The

first kind of skills refers to the ideal of high-quality

observations, that is, observations that are capable of

generating valid statements of fact. This ideal is traditionally

but rather inadequately designated "objectivity";

it requires our propositions or claims to possess observational qualities

such as intersubjective transferability and controllability,

repeatability over time, adequate precision, and clarity with

respect to both the object and the method of observation.

The

second kind of skills refers to the ideal of cogent reasoning,

that is, processes of (individual) reflection and (intersubjective)

argumentation that generate valid statements about the meaning

(interpretation, justification, relevance) of observations.

This ideal is traditionally designated "rationality";

it requires our propositions to possess communicative and argumentative

qualities such as syntactic coherence, semantic comprehensibility,

logical consistency with other statements, empirical content

(truth), pragmatic relevance and normative legitimacy (rightness).

Both

requirements raise important issues for the concept of research

competence. How can we know whether we "really" know,

that is, whether our observations are high-quality observations

or not? And if we can assume that they are, how can we know

whether we understand their meaning correctly and draw the "right"

conclusions, that is, that we reason and argue correctly?

Competent

observation and argumentation require one another A

particular difficulty with the two requirements is indeed that they

are inseparable. This becomes obvious as soon as we consider

the nature of the "facts" that quality observations

are supposed to establish:

Facts

are what statements (when true) state; they are not what statements

are about [i.e., objects]. They are not, like things or happenings

on the face of the globe, witnessed or heard or seen, broken

or overturned, interrupted or prolonged, kicked, destroyed,

mended or noisy. (Strawson, 1964, p. 38, cf. Ulrich, 1983,

p. 132)

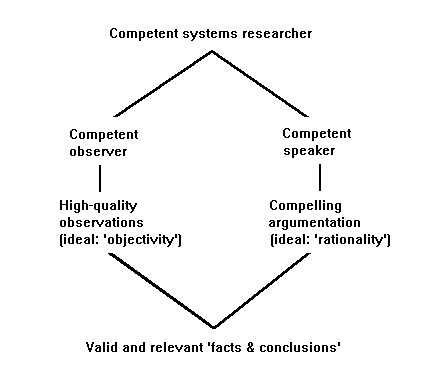

That

is to say, facts are not to be confused with objects of experience;

they cannot be experienced (they are statements rather than

objects), just as objects of experience cannot be asserted (only

statements can). Facts, because they are statements, need to

be argued. Accordingly observational and argumentative competencies

must go hand in hand; they are but

two sides of one and the same coin. (Fig. 1)

Fig.

1: Two dimensions of competence

in systems thinking and research: observational and argumentative.

Each

dimension entails specific validity claims, the redemption of

which may, however, involve claims that refer to the other dimension.

Let

us consider some of the specific requirements on each side of

the coin. On the argumentative side, Habermas' (1979; 1984-87)

well-known model of rational discourse gives us a framework

for analyzing the difficult implications of the quest for compelling

argumentation or, as he puts it, "communicative competence."

What

makes a good argument?

According to this model, a competent speaker would have to be

able to justify (or "redeem," as Habermas likes to

say) the following validity claims that all rationally motivated

communication entails and which together amount to a "universal

validity basis of speech":

- Comprehensibility:

a claim that entails the obligation to express oneself so

that the others can hear and understand the speaker; it

cannot be redeemed discursively but merely through one's

communicative behavior.

- Truth:

a claim that entails the obligation to provide grounds for

the empirical content of statements, through reference to

quality observations and through theoretical discourse.

- Rightness:

a claim that entails the obligation to provide justification

for the normative content of statements, through reference

to shared values (e.g., moral principles) and through practical

discourse.

- Truthfulness:

a claim that entails the obligation to redeem the expressive

content of statements by proving oneself trustworthy, so

that the others can trust in the sincerity of the speaker's

expressed intentions; again this cannot be redeemed discursively

but only through the consistency of the speaker's behavior

with the expressed intentions.

(adapted from Habermas, e.g., 1979, pp. 2-4,

63-68)

Since

these validity claims are always raised simultaneously in all

communication, whether explicitly or implicitly, it becomes

apparent that a competent researcher must be prepared to substantiate

statements of fact not only through credible reference to quality

observations but also through theoretical and practical discourse,

so as to convince those who doubt or contest the "facts" in

question of the validity of their underlying, theoretical and normative

presuppositions.

What

makes a good observation? Similar

difficulties arise with the requirement of substantiating the

quality of observations. Observations – or more precisely, observational

statements – always depend on the construction

of some sort of objects that can be observed and reported upon.

Depending on the situation, these constructions may need to

rely on different notions of what kinds of objects

lend themselves to quality observations. A conventional notion

of "objects" assumes that the objects of observation can be construed

to be largely independent of the purposes of both the observer

and the user of the generated knowledge. In such a conventional

account, a claim to quality observations will entail the obligation

to redeem at least the following requirements:

- Validity:

the observation observes (or measures) what it is supposed

to observe (or measure).

- Reliability:

the observation can be repeated over time and provides (at

least statistically) a stable result.

- Transferability:

the observation can be repeated by other observers and in

that sense proves to be observer-independent (a validity

claim that is often subsumed under 2).

- Relevance:

the observation provides (together with other observations)

information that serves as a support for a statement of

fact, or for an argument to the truth of some disputed fact.

The

"Challenge of the User":

Towards a richer construction of high-quality observations and

arguments Historically

speaking, these or similar assumptions characterized the rise

of the empirical sciences (especially the natural sciences)

about three centuries ago. More recently, however, with the

extension of scientifically motivated forms of inquiry to ever

more areas of human concern, competent research increasingly

faces the difficulty that contrary to the original assumptions,

quality observations cannot be assumed to be independent of

either the observer or the user or both. As for instance de

Zeeuw (1996, pp. 2f and 19f /2001, pp. 1f and 25f) observes, science is now more

and more faced with the challenge of the user, that is,

the task of constructing quality observations so that they allow users

to have a voice inside science. This is different from conventional

science which, because of its underlying notion of non-constructed,

observer- and user-independent objects, depends on the exclusion

of users.

Typical

examples are research efforts in the domains of therapy (e.g.,

psychiatry), social work and social planning (e.g., care for

the elderly or fighting poverty), business management (e.g.,

organizational design, management consultancy), and public policy-making

(e.g., policy analysis, evaluation research). "Patients,"

"clients," and "decision-makers" increasingly

claim a voice in the making of the observations of concern to

them, so that "diagnoses," "help" or "solutions"

are not merely imposed upon them without considering their

observations. What does it mean for a researcher to assure high-quality

observations under such circumstances?

Three

phases of science: expanding the reach of high-quality observation De

Zeeuw has discussed this issue extensively (e.g., 1992, 1995,

1996/2001, 2005). He distinguishes three notions of "objects"

that allow quality observations responding to different circumstances

(the examples are mine): non-constructed objects

(e.g., the seemingly given, observer-independent objects of

astronomy such as the celestial bodies and phenomena),7)

constructed objects (e.g., groups such as "the

poor" or "the upper class" as objects of the

social sciences, or "systems" as objects of the systems

sciences), and self-constructed objects (e.g., expressions

of human intentionality as objects of study in social systems

design, organizational analysis, environmental and social impact

assessment, action research etc., where the construction of

the objects to be observed is left to those who are concerned

in the observations at issue, be it because they may be affected

by them or because they may need them for learning how to achieve

some purpose, or else because they may be able to contribute

some specific points of view). These three

notions of objects give rise to three developments of science

which de Zeeuw calls "first-phase," "second-phase,"

and ‘third-phase" science.

If

I understand de Zeeuw correctly,8)

the constructed objects of second-phase science distinguish

themselves from objects of first-phase science

in that they depend on the observer's purpose (e.g., the improvement

of some action or domain of practice); the self-constructed

objects of third-phase science depend, moreover, on the full

participation of all the users of the knowledge that is to be

gained.

The

emancipatory turn The

notion of competent research that I propose here and

which is also contained in my work on critical heuristics (CSH),

critical systems thinking (CST) for citizens, and critical pragmatism, is certainly

sympathetic to the idea of combining the "challenge of

the user" with an adequate notion of (objects of) high-quality

observations, a notion of quality that – in my terms – would

give a competent role to all those concerned in, or affected

by, an inquiry. I thus quite agree with de Zeeuw (1996, p. 19;

2001, p. 24)

when he refers to CSH as an example of a type of inquiry that focuses

on "the

need to give users in general a voice inside science,"

so as to overcome the conventional limitation of quality observations

to objects that are constructed by researchers without the full

participation of users. It should be noted clearly, however,

that CSH aims beyond the instrumental purpose of improving the

quality of "scientific" observations; it also aims

at emancipating ordinary people from the situation of incompetence

and dependency in which researchers and experts frequently put

them in the name of science. It aims at the earlier-mentioned

insight that what in our society counts as knowledge is always

a question of what ought to count as knowledge, whence

the issues of democratic participation and debate and of the

role of citizenship in knowledge production become essential

topics. That is why I find it important to associate the challenge

of the user with the goal of allowing citizens (as well as researchers)

to acquire a

new competence in citizenship

(Ulrich, 1995, 1996a, b, 1998b, 2000, 2012a).

Towards

a New Symmetry of Critical Competence For

me, a fundamental source of such competence consists in learning

to handle the boundary judgments that inevitably underpin all

application of research and expertise. The crucial point is

that when it comes to boundary judgments, researchers or experts

have no in-principle advantage over ordinary citizens:

When

an expert, by reference to his theoretical knowledge, defines

"the problem" at hand or determines "the solution,"

he must always presuppose such boundary judgments. To define

the problem means, in fact, to map the social reality (or the

social system) to be dealt with; to determine the solution

means to design a better social reality (or social system).

And since every map or design depends on previous boundary judgments

(or whole systems judgments) as to what is to be included in

it and what is to belong to its environment, it is clear that

no definition of "the problem" or "the solution"

can be objectively justified by reference to theoretical knowledge.

It can only be critically justified by reference to both the

transparency of values and the consent of all the affected citizens.

The first implication is trivial:

no amount of expertise (theoretical knowledge) is ever sufficient

for the expert to justify all the judgments on which his recommendations

depend. When the discussion turns to the basic boundary

judgments on which the exercise of expertise depends, the expert

is no less a layman than are the affected citizens.

The

second implication is less trivial, in that it seems to contradict

common sense: no expertise or theoretical knowledge

is required to comprehend and to demonstrate that this is so.

The necessity of boundary judgments can be intuitively grasped

by every layman: since no one can include "everything"

in his maps or designs, he cannot help presupposing some boundaries.…

Anybody who is able to comprehend the [relevance of such] boundary

judgments is also able to see through the dogmatic character

of the expert's "objective necessities." (Ulrich,

1983, p. 306, italics original)

To

be sure, experts are still needed to inform all those without

special expertise in an issue at hand (and virtually all of

us find themselves in this position most of the time) about

the likely or possible consequences of different boundary assumptions,

and thus about the options for efficacious action and resulting

kinds of improvement, side-effects, and risks. But they have

no privileged position when it comes to choosing among

these options, and thus among the competing boundary judgments:

Experts

may be able to contribute to the task of anticipating the

practical consequences of alternative boundary judgments; but

they cannot delegate to themselves the political act of sanctioning

the normative content of these consequences. (Ulrich, 1983, p. 308)

This

explains why professionals, counter to what one might expect,

have no natural advantage over ordinary citizens with respect

to boundary judgments. There is, in principle, a symmetry

of critical competence (Ulrich, 1993, p. 604) between

citizens and professionals, as both sides have an equal chance

of handling boundary questions in self-reflective and transparent

ways (for fuller accounts, see Ulrich, 1983, entire ch. 5, esp.

pp. 305-310; 1987, p. 281f; 1993, pp. 599-605,

2000, p. 254). The need for a careful

and open handling of boundary judgments thus translates into

a new skill of boundary critique, a skill that in principle

is available equally to citizens and to professionals as it

does not depend on any special expertise that would be beyond

the comprehension of ordinary people. Once we understand

this implication, our concept of high-quality observation of

situations will change, as will also our concept of compelling

argumentation.

Limitations

of Science Theory and Research Methodology But

of course, giving users a more competent voice within research

does not answer all the questions raised by the search for valid

and relevant "findings and conclusions." The deeper

reason for this is that we are dealing with an ideal. A competent

researcher will always endeavor to make progress toward it,

while never assuming that he or she has attained it.

Wanting

theories of truth and rationality We do not currently

have, and chances are we will never have, operational

theories of "true" knowledge and "rational"

argumentation. Given this situation, along with the ideal character of the quest for scientific validation,

we should not expect philosophers of science and theorists of

research methodology, either, to come up with safe and sufficient

guidelines, not any more than practicing researchers.

As far as the problem of ensuring high-quality

observations is concerned, the basis for such guidelines would

have to be some sort of a practicable correspondence theory

of truth. Such a theory would have to explain how we can

establish a "true" relationship – a stable kind of

"correspondence" – between statements of fact and

reality. But then, "reality" is not accessible except through

the statements of observers who, apart from being human and

thus imperfect observers, construct it dependent

on their particular views and interests and corresponding boundaries

of concern (i.e., boundary judgments). It is thus clear that such

a theory is basically impossible. The ideal – if indeed

it is a proper ideal – will remain just that, a mere ideal.

Similarly,

with regard to the problem of securing compelling argumentation,

the necessary basis would consist in a practicable theory of

"rationally" argued consensus. Such a discourse

theory of rationality would have to explain how a consensus

can be shown to be justified rather than merely factual, that

is, what kind of arguments are necessary to support it and what

conditions could ideally warrant these arguments. But as we

have learned from Habermas' (1979) analysis of the "ideal speech

situation," such a theory cannot make those ideal conditions

real. This is a topic that I consider essential for developing

our contemporary concept of science so as to meet the challenge

of the user, but it leads far beyond the scope of the present,

introductory essay. Interested readers can find some of my efforts

to come to terms with the difficult path to communicative rationality

elsewhere (e.g., Ulrich, 1983, Ch. 2; 2009a, b; 2013a)

Insofar

as the methods of natural science appear to provide a proven

tool for ensuring scientific progress, many natural scientists

may disregard the lack of philosophical grounding without worrying

too much. The social sciences and the applied disciplines are

in a less comfortable position, however. The way they deal with

these issues is bound to affect the findings and conclusions

they will be able to establish. Applied researchers need to

be especially careful as to what their quest for competence

means and in what respects it can or cannot be grounded epistemologically and methodologically.

As students of the applied disciplines, how can you square the

circle and hope to become a competent researcher or professional

despite the lack of sufficient epistemological and methodological

guidelines?

Methodological

Pluralism The unavailability of a satisfactory

answer is probably responsible for the postmodern rise of pluralism

in epistemological and methodological thought, sometimes also

called "methodological complementarism." Since there

is no single theoretical and methodological framework that would

be best for all research tasks and circumstances, so goes the

reasoning, the value of research depends on careful choice and

combination of methodologies and conforming methods. Accordingly,

meta-level frameworks for selecting proper research approaches

need to be developed to support sound practice. In the management sciences, for

example, this so-called

"methodology choice" approach

has been heralded particularly in the writings of Jackson (e.g.,

1987, 1990, 1991, 1997, 1999), Midgley (e.g., 1992, 1997),

and Mingers (Mingers and Brocklesby, 1996; Mingers and Gill,

1997). In different ways and partly critical of this

meta-level approach, which raises unsolved theoretical problems

of its own, methodological pluralism or complementarism also informs

the work of other authors in

the field, including my own work (e.g., Linstone, 1984 and 1989; Oliga, 1988; Ormerod,

1997; Ulrich, 1988, 2003; 2012c, d, e, 2013b, 2017; White and Taket, 1997).

But of

course, the call for epistemological and methodological pluralism,

justified as it is by the lack of satisfactory theories of knowledge and of rationality,

merely

makes a virtue of necessity. It cannot conceal the fact that

if by "competent" research we mean a form of inquiry

that would give us sufficient reasons to claim the validity

of our findings and conclusions, the quest for competence in

research remains chimerical. The methodology choice approach,

as we already found above in a different context (discussing

the mistaken idea that theoretically grounded methods can justify

practice), just doesn't carry far enough.

The

ongoing quest for good practice For

a tenable practice of research, we still need additional guidelines.

Two sources of guidelines have become particularly important

for my understanding of competence in research:

(a) Rethinking

the relationship of theory and practice: Instead of seeking a basis for claims to knowledge and rationality

in the scientific qualities of research alone, we might be better

advised to seek to base them in a proper integration of research

and practice. The issue that comes up here is the precise model for mediating

theory and practice, or science and politics,

that should underpin our understanding of competence in applied

research.

(b)

The critical turn of practice: Instead of seeking to validate claims to knowledge and rationality

positively, in the sense of ultimately sufficient justification,

we might be better advised to defend them critically only, by

renouncing the quest for sufficient justification in favor of

the more realistic quest for a sufficient critique, that is,

for a systematic effort of laying open justification deficits.

The issue here is what in my writings I describe as the "critical

turn" (or, in some more specific contexts, also as the "critically-heuristic,"

"critically-discursive," and "critically-normative"

turns) of our notions of competence, knowledge, science, rationality,

good practice, and so on, and as the consequent quest for an

at least critical solution to the problem of practical

reason, along with the critical significance of the systems

idea for such a solution.9)

Mediating

theory

and practice Ever since the rise of

science, there has been a hope that political practice, that

is,

the use of power, could be enlightened by science. At the bottom

of this issue lies the question of the proper relationship between

science and society, between technically exploitable knowledge

and normative-practical understanding (and improvement) of the

social life-world, between "theory" and "practice."10)

From

Aristotelian praxis to decisionism Until

the rise of science, Aristotle's (1981, 1985) view of rational

practice (praxis)

as a non-scientific domain that was to be grounded in the ethos

of the polis and in the model of proper conduct or "excellence"

(arete) provided by virtuous individuals, was generally

accepted. The crucial link between reason and practice consisted

for Aristotle in his belief that "we cannot be intelligent

without being good" (1985, Book VI, Ch. 12). Virtues of

character and of thought were the human qualities that

mattered most for proper praxis, much more than reliance

on theoretical knowledge (theoria) and technical

skills (poiesis). Interestingly, these virtues were not

simply given to individuals but were the result of hard work

and of a persistent, life-long quest for excellence or, as we

say in this essay, for competence. Modern as this Aristotelian

concept is, there is a basic difference to the quest for competence

that inspires the present essay: Aristotle saw the task

and virtue of excellence (or competence) in its supporting the

traditioned,

conventional way of life of the community and thus would hardly

have expected it to pursue a critical or even emancipatory intent

along the lines of "boundary critique."

For some

one and a half millennia after Aristotle, this conventionalist,

but ethically grounded notion of rational practice prevailed. The alternative idea of

grounding it in science

and research did not arise before the modern

age. It was the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

who in the middle of the seventeenth century proposed a first design for the scientization of politics. His

insight was that practical issues raise questions that are scientifically

accessible

insofar as they require theoretical or technical knowledge.

Once these theoretical or technical questions had been identified,

the remaining questions would then properly remain inaccessible

to science as they required genuinely normative, subjective

decisions that lie beyond rationalization through theory

or technique. Thus decisionism was born, the doctrine

that practical questions allow of scientific rationalization

as far as they involve the choice of means; for the rest, they

can only be settled through the (legitimate) use of power. Auctoritas,

non veritas, facet legem, became Hobbes' motto: "Power

rather than truth makes the law." The limited function

of science, then, consists in informing those in a situation

of (legitimate) power about the proper choice of means for their

ends, according to the guideline: "Knowledge serves

power."

From

the decisionistic to the technocratic model For

the Enlightenment thinkers, this could not be the last word

on the matter. Veritas, non auctoritas, facet legem, that

is, "Truth rather than power makes the law," was postulated

by the French Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(1712-1778) as a counterpoint against Hobbes. It was to take

nearly two centuries for Rousseau's postulate to acquire some

empirical content (descriptive validity) in addition to its

normative content. The growth of administrative and scientific

tools for rationalizing decisions, exemplified by the development

of computers, decision theory, and systems analysis in the middle

of the twentieth century, led to a partial reversal of the relationship

between the politician and the expert or researcher:

the researcher's understanding of real-world issues now increasingly

tends to determine the need and criteria for political action.

One need only think of environmental issues to realize how much

science nowadays defines the factual constraints to which politicians

must succumb.

What

remains to politics, then, is paradoxically the choice of the

means that are capable of responding to the needs that have

been defined by the experts. As a former chief evaluator in

the public sector, I have often experienced this peculiar

reversal of roles: I was expected to come

up with "scientific" findings and conclusions as to

what needed to be done, so that the politician could then justify

his chosen measures (or his inactivity) by referring to the

recommendations of the evaluation researcher. The danger is that the genuine

function of politics, to ensure legitimate decisions on issues

of collective concern, is in effect delegated to researchers

who, because they hold no political mandate, are not democratically

accountable.

To

the extent that this reversal of roles takes place, the decisionistic

model of the mediation between science and politics becomes

technocratic. In the technocratic model, political debates

and votes are ultimately replaced by the logic of facts; politics

fulfils a mere stopgap function on the way towards an ever-increasing

rationalization of power (Habermas 1971, p. 64). Knowledge no

longer serves power, as in the decisionistic model; knowledge

now is power.

Max

Weber's solution attempt The

German sociologist and philosopher Max Weber (1864-1920, see

1991) foresaw this tendency. As a bulwark against technocracy,

he sought to strengthen the decisionistic model by reformulating

it more rigorously. He tried to achieve this by conceiving of

an interpretive social science that could explain (and

thus rationalize) the subjective meaning of individual actions

or decisions in terms of underlying motivations of people, without

thereby presupposing value judgments of its own. Interpretive

social science was to describe and explain value judgments

but not to make or justify them. In this limited sense

it could then support subjective decisions or actions and promote

their rationality. Rather like Hobbes, Weber thus found that

decisions or actions indeed admit of scientific explanation,

namely, insofar as they can be shown to represent a "purpose-rational"

pursuit of motivations.

At

the bottom of this view is a concept that has remained very

influential to this day, Weber's means-end dichotomy.

It says that decisions on ends and the choice of means can be

separated, in that the latter do not require value judgments

of their own and hence are accessible to scientific support.

This concept of purposive-rationality permits a rational

choice of efficacious means; but it cannot deal with the rationality

of the purposes they serve, much less ensure it. In this respect

it falls back onto the very decisionism it was meant to overcome

or to "rationalize."

Quite

in the tradition of Hobbes, Weber in effect relegated the choice

of ends once again to a domain of genuinely irrational

– because subjective and value-laden – political and ethical

"decisions." Weber was willing to pay this price since

he hoped to achieve a critical purpose: lest it become

technocratic, science should not misunderstand itself as a source

of legitimation for value judgments on ends. That was the essential

concern that his famous slogan cited above meant to capture:

"Politics is out of place in the lecture-room." (Weber,

1991, p. 145).

The

problem with this self-restriction of science is not only that

the question of proper ends remains unanswered – the effectiveness

and efficiency of means, when used for the wrong ends, brings

about not more but less rational practice. The problem is also,

and more fundamentally, that it does not achieve its critical

intent, as self-restriction to questions of means does not in

fact keep research free of value implications. The reason is

that alternative means to reach a given end may have different

practical implications for those affected by the measures taken.

For example, alternative proposals for radioactive waste disposal

may impose different risks and costs on different population

groups, including future generations. That is to say, decisions

about means, just like decisions about ends, have a value content

that is in need of both ethical reflection and democratic legitimation.

Whether or not their claim to purposive-rationality is backed

by science makes little difference in this regard.

Weber's

conception of a value-free, interpretive social science breaks

down as soon as one admits this implication. Once this is clearly

understood, it seems almost unbelievable how uncritically a

majority of contemporary social and applied scientists still

adhere to the dogma that means and ends are substantially distinct

categories, so that only decisions on "ends" are supposed

to involve value judgments while the choice of "means"

is understood to be value-neutral with regard to given ends,

that is, to be the legitimate business of science (cf. Ulrich,

1983, p. 72).

The

pragmatist model of Jurgen Habermas In

order to overcome the shortcomings of both the decisionistic

and the technocratic models of relating theory and practice,

we need another model. Such a model will have to replace the

faulty means-end dichotomy by a fundamentally complementary

understanding of means and ends, just as of theory and practice

(cf. Ulrich, 1983, pp. 222 and 274; 1988, pp. 146-149;

1993, p. 590; 2011, pp. 13-18). In this model, the selection

of means and the selection of ends are not separable, for the

rationality of either depends on the rationality of the other.

Moreover, each decision has a value content of its own, although

this value content again is not independent of the value content

of the other decision. It is the merit of Jurgen Habermas (1971)

to have elaborated a model that conforms to these requirements.

He calls it the pragmatist model.

In

the pragmatist model, neither politicians nor researchers possess

an exclusive domain of genuine competence, nor can either side

dominate the other. Caught in an intricate "dialectic of

potential and will" (Habermas, 1971, p. 61), they depend

on each other for the selection of both means and ends. The

strict separation between their functions is replaced by a critical

interaction, and the medium for this interaction is discourse.

Its task is to guarantee not only an adequate translation of

practical needs into technical questions, but also of technical

answers into practical decisions (cf. Habermas, 1971, p. 70f).

In

order to achieve this double task, the discourse between politicians

and researchers must, according to Habermas (1979), be rational

(or "rationally motivated") in the terms of his ideal

model of rational discourse. That is, the discourse must be

"undistorted" and "free from oppression."

The difficulty is, once again, that we are dealing with an ideal.

Even where the discourse between politicians and experts occasionally

results in an undisputed consensus, how can we ever be sure

that the consensus is not merely factual rather than rational?

Realistically speaking, we can never be sure; for the discourse

would then have to include not only the effectively involved

politicians and researchers but all those who are actually or

potentially concerned or affected by the decision in question,

including the unborn or other parties that cannot speak for

themselves. Moreover, it would have to enable all of them to

play a competent role. The pragmatist model thus leads us back

to the fundamental concern of critical systems heuristics, namely,

that we need to develop a practicable and non-elitist "critical

solution" (rather than a complete "positive solution")

to the unachievable quest for securing rational practice.

Before

we turn to this idea of an at least critical solution of the

problem of practical reason, let us summarize our findings with

respect to a competent researcher's understanding of the relationship

of theory and practice: a competent researcher will (1)

examine critically the role she or he is expected to play in

respect to practice; (2) analyze which model of the relation

of theory and practice is factually assumed in her or his mandate,

and which model might be most adequate to the specific situation

at hand; and (3), where the appropriate answer appears to consist

in working toward a pragmatist model, a competent researcher

will seek to consider all those people actually or potentially affected

and, to the extent that their actual participation is feasible,

will also seek to put them in a situation of competence rather

than their usual situation of (supposed) incompetence.

The

Critical Turn

The "critical turn" is the

quintessence of much of what I have tried to say in this essay.

The quest for competence in research and professional practice

entails

epistemological and ethical requirements that we cannot hope

to satisfy completely. I am thinking particularly of requirements

such as identifying all conceivable "practical implications"

of a proposition; assuming proper boundary judgments; securing

high-quality observations as well as compelling argumentation;

dealing properly with the practical and normative (ethical,

moral) dimension of our

"findings and conclusions"; mediating adequately between research

and practice; and facing the "challenge of the user."

In

view of these and other requirements that we have briefly considered,

the usual notion of competent research becomes problematic.

I mean the notion that as competent researchers we ought to

be able to justify our findings and conclusions in a definitive,

compelling way. As an ideal, this notion of justification is

certainly all right, but in practice it tempts us (or those

who adopt our findings and conclusions) into raising claims

to validity that no amount of research competence can possibly

justify.

I

suggest that we associate the quest for competence with a more

credible notion of justification. First of all, let us acknowledge

openly and clearly that we cannot, as a rule, sufficiently justify

the results of our research. This need not mean that we should

renounce any kind of validity claims, say, regarding

the quality of our observations or the rationality of our conclusions.

The fact that we cannot fully justify such claims does not mean

that we cannot at all distinguish between higher and lower quality,

or more or less compelling argumentation. It means, rather, that

the manner in which we formulate and handle validity claims

will have to change. We must henceforth qualify such claims

very carefully, by explaining to what extent and how exactly

they depend on assumptions or may have implications that we

cannot fully justify as researchers, but can only submit to

all those concerned for critical consideration, discussion,

and ultimately, choice.

Towards

a new ethos of justification It

is the researcher's responsibility, then, to make sure that

the necessary processes of debate and choice can be handled by

the people concerned in as competent a way as possible.

To this end, a competent researcher will strive to give those concerned

all the relevant information as to how her or his findings came

about and what they may mean to different parties. Moreover,

it becomes a hallmark of competence for the researcher to undertake

every conceivable effort to put those concerned in a situation

of meaningful critical participation rather than of incompetence.

This

is the basic credo of the critical turn that I advocate in our

understanding of research competence. It amounts to what elsewhere

(Ulrich, e.g., 1984, pp. 326-328, and 1993, p. 587) I have called

a "new ethos of justification," namely, the idea that

the rationality of applied inquiry and design is to be measured

not by the (impossible) avoidance of justification deficits

but by the degree to which it deals with such deficits in a

transparent, self-critical, and self-limiting way.

Since

in any case we cannot avoid justification deficits, we should

seek to understand competence as an effort to deal self-critically

with the limitations of our competence, rather than trying

to avoid or even conceal them. The critical

turn demands from researchers a constant effort to be "on

the safe side" of what they can assume and claim in a critically

tenable way. It demands a Socratic sense of modesty and self-limitation

even where others may be willing to grant the researcher the

role of expert or guarantor. Once you have grasped this meaning

of the critical turn, it will become an irreversible personal

commitment. Kant, the father of Critical Philosophy, said it

well:

This

much is certain, that whoever has once tasted critique will

be ever after disgusted with all dogmatic twaddle. (Kant, 1783,

p. 190).

I

invite you to "taste critique" and to give it a firmly

established place in your notion of competence!

Tasting

critique As

students of systemic research and practice, you might begin this

critical effort by understanding the systems idea

critically, that is, using it as a tool of reflective research and practice

rather than a basis for claiming any kind of special rationality

and expertise (e.g., in handling tasks of systems analysis,

design, and management, or any kind of professional intervention

with a systemic outlook). Thus understood, the

critical turn will change the way in which we employ systems concepts

and methodologies and in fact, any other methodologies. Rather than understanding systems

thinking as a ground

for raising claims to rationality and expertise, or even some kind of superior

"systemic" rationality, we shall understand it from now on as tools for critical reflection. In other words,

we will use it more for the purpose of finding questions than

for finding answers.

A

crucial idea that can drive the process of questioning is that

of a systematic unfolding of both the empirical and the normative

selectivity of (alternative sets of) boundary judgments, that

is, of how the "facts" and "values" we recognize

change when we alter the considered system (or situation) of

concern. I have referred to this process earlier in this paper

as a process of systematic boundary critique.

Two core

concepts of boundary critique that I have often used to explain the idea are the

"eternal triangle" of observations, valuations, and

boundary judgments, and the related concept of a "systemic

triangulation" of our findings and conclusions (or related

claims). Interested readers will find two introductory essays

that are written for a wide audience of researchers, professional people,

decision-makers, and citizens in Ulrich (2000 and 2017).

A

third key concept of boundary critique that I would like to

mention here concerns the way boundary critique can help promote

a better "symmetry of critical competence" among people

with different backgrounds and concerns – those who in a project

have the say and those who don't; those involved and those affected

but not involved; experts and non-experts; professionals and

the citizens they are supposed to serve. The basic point should

by now be clear: whatever skills in the use of research methods, theoretical

knowledge, and professional experience or any other kind of expertise a researcher may possess

– when it comes to boundary judgments, researchers are

in no better position than other people. Whoever claims the

(objective) validity of some findings or the (superior) rationality

of the conclusions derived from them without at the same

time explaining the specific boundary judgments on which these

claims depend, can thus be shown to be arguing on slippery grounds.

Boundary

critique for citizens Based on this concept of

a fundamental symmetry of competence in regard to boundary judgments, boundary

critique can also serve as a restraint upon unwarranted claims

on the part of researchers or other people who do not employ

systems concepts and methodologies (or any other methodologies) as self-critically

as we might wish. If reflective research practice is not to

remain dependent solely on the good will of researchers and

professionals, it is indeed

important that other people can challenge their findings and

conclusions by making visible the boundary judgments on which

they rely. See Ulrich (1993) for a fuller account of this important

implication of boundary critique. Readers will also find

this tool described in my writings in terms of an "emancipatory employment

of boundary judgments" or shorter, of "emancipatory boundary

critique" (e.g., 1996a, 1987, 2000, 2003).

I

believe that ordinary people, provided they receive an adequate

introduction to the idea of boundary judgments, can understand

the conditioned nature of all findings and conclusions and

can then also learn to challenge unwarranted claims on the part of experts

in an effective way, without depending on any special expert

knowledge that would not be available to them. No special expertise is required because

no positive claims to validity are involved; it is quite sufficient

for such critical argumentation to show that a claim relies

on some crucial boundary judgments (say, as to what "improvement" means

and for whom it should be achieved) that has not been laid

open and for which there are options.

The employment of boundary

judgments for merely critical purposes has this extraordinary

power because it is a perfectly rational form of argumentation:

its relevance and validity cannot be disputed simply by accusing the critic of lacking

expert knowledge. For this reason I am convinced that it is

able to give not only researchers and professionals but also ordinary citizens

a new sense of competence. I have explained this emancipatory

significance of the concept of boundary judgments elsewhere

in more detail and in various terms, partly also in terms of Kant's (1787) fundamental

concept of the "polemical" employment of reason (see, e.g.,

Ulrich, 1983, pp. 301-314; 1984, pp. 341-345;

1987, p. 281f; 1993, pp. 599-605; 1996a, pp. 41f; 2000, pp.

257-260; and 2003, pp. 329-339). But as I just hinted, you do

not need to become an expert of CSH to understand and practice

the idea of boundary critique.

Conclusion

At the outset I proposed that to "understand"

means to be able to formulate a question. I suggested that in

order to become a competent researcher, it might be a good idea

for you to reflect on the fundamental question to which your

personal quest for competence should respond.

I

hope I have made it sufficiently clear in this paper that you

will have to find this question yourself. Nobody else can do

it for you. In order to assist you in this endeavor, I have

tried to offer a few topics for reflection. There are, of course,

many other topics you might consider as well; my choice may

perhaps serve as a starting point for finding other issues you

find important for developing your notion of competence.

I

also proposed at the outset that for some of you, systems thinking

might be part of the answer. But should it? Well, I am inclined

to say, it depends: if you are ready to take the critical

turn and to question the ways in which systems thinking can

increase your competence, then it might indeed

become a meaningful part of your personal understanding of competence.

By reflecting on what might be the fundamental question to which

a critical systems perspective gives part of the answer, you

might begin to understand more clearly what exactly you expect

to learn from studying systems thinking and how this should

contribute to your personal quest for competence.

I

did not promise you that it would be easy to formulate this

fundamental question. It may well be that only by hindsight,

towards the end of your professional life, you will really be

able to define it. In the meantime, it will be necessary to

rely on some tentative formulations, and more importantly, to

keep searching. Only if your mind keeps searching for the one

meaningful question can you hope to recognize it when you encounter

it. Sooner or later you will find at least a preliminary formulation

that proves meaningful to you.

My

basic question (an example) Perhaps

you wish you had an example. Should I share my tentative question

with you? At the end of this essay, I hope you are sufficiently

prepared not to mistake it for your own question. I first encountered this

fundamental question in the year 1976, when I

moved to the University of California at Berkeley (UCB) to study

with West Churchman, who had helped to pioneer the fields of

operations research and management science in the 1950s and

then, since the 1960s, became a pioneer and leading philosopher

of the systems approach. Churchman used to begin his seminars

with a question! He then asked his students to explore the meaning

of that question with him, and that's what I have kept doing

ever since. This is what Churchman wrote up on the blackboard:

Can

we secure

improvement

in the human

condition

by

means of the human

intellect?

For

Churchman, each one of the underlined key expressions in the

question – "secure," `"improvement," "human

condition," and "human intellect" – pointed to

the need for a holistic understanding of the systems

approach. We cannot hope to achieve their fulfillment without

a sincere quest for "sweeping in" (Singer, 1957; Churchman,

1982, pp. 117, 125-133; cf. my appreciations in Ulrich, 1994

and 2004, pp. 1126-1128) all aspects

of an issue that might conceivably be relevant, that is, ideally,

for "understanding the whole system" (Churchman, 1968,

p. 3). Churchman's life-long quest to understand the question

thus led him to see the systems approach as a heroic

effort. A systems researcher or planner who is determined to

live up to the implications of the question is bound to become

a hero!

My

own endeavor to come to terms with the question was a little

less heroic. For me, each of the question's key expressions

points to the need for a critical turn of the systems

approach. We cannot hope to do justice to them without a persistent,

self-reflective effort to consider the ways in which we fail

to be sufficiently holistic. Since boundary judgments are always

in play, all our attempts to secure knowledge, understanding,

and improvement are bound to be selective rather than comprehensive.

We must, then, replace the quest for comprehensiveness with

a more modest, but practicable, quest for boundary critique.

This is why in my work on CSH, the principle of boundary critique had to replace the sweep-in

principle as a methodological core concept of competent research

and practice (Ulrich, 2004, p. 1128).

At

least in hindsight, Churchman's question makes it easier for

me to understand why I had to struggle so much to clarify my

understanding of the systems idea, and why I ended up with something

like critical systems heuristics and its central concept of

boundary critique. It is because I tried, and still try, to

understand systemic research and practice so that it responds

to that fundamental question. There is no definitive answer

to the question, of course; but that surely does not dispense

me (or us, inasmuch as you agree) from struggling to gain at least some critical competence

in dealing with it.

I wish you success

in your quest for competence.

|

|

|

|

Notes

1) The British philosopher, historian,

and archaeologist R.G. Collingwood (1939/1983, 1946) was perhaps

the first author to systematically discuss the logic of

question and answer as a way to understand the meaning of everyday

or scientific propositions. As he explains in his Autobiography

(1939):

I

began by observing that you cannot find out what a man means

by studying his spoken or written statements, even though he

has spoken or written with perfect command of language and perfectly

truthful intention. In order to find out his meaning you must

also know what the question was (a question in his mind, and

presumed by him to be in yours) to which the thing he has said

or written was meant as an answer.

It

must be understood that question and answer, as I conceived

them, are strictly correlative.… [But then,] if you cannot tell

what a proposition means unless you know what question it is

meant to answer, you will mistake its meaning if you make a

mistake about that question.… [And further,] If the meaning

of a proposition is correlative to the question it answers,

its truth must be relative to the same thing. Meaning,

agreement and contradiction, truth and falsehood, none of these

belonged to propositions in their own right, propositions by

themselves; they belonged only to propositions as the answers

to questions. (Collingwood, 1939/1978, pp. 31 and 33, italics

added)

While

remaining rather neglected in fields such as science theory

and propositional logic, it was in the philosophy of history

(the main focus of Collingwood, esp. 1946), along with hermeneutics

(Gadamer, 2004), and argumentation theory (Toulmin, 1978,

2003) that Collingwood's notion of the logic of question and

answer was to become influential. In hermeneutic terms, the

questions asked are an essential part of the hermeneutical horizon

that shapes what we see as possible answers and what meaning

and validity we ascribe to them. In his seminal work on hermeneutics,

Truth

and Method, Gadamer (2004) notes:

Interpretation

always involves a relation to the question that is asked of

the interpreter.… To understand a text means to understand this

question.… We understand the sense of the text only by acquiring

the horizon of the question – a horizon that, as such, necessarily

includes other possible answers. Thus the meaning of a sentence

… necessarily exceeds what is said in it. As these considerations

show, then, the logic of the human sciences is a logic of the

question.

Despite Plato we are not very

ready for such a logic. Almost the only person I find a link

with here is R.G. Collingwood. In a brilliant and telling critique

of the Oxford "realist" school, he developed the idea

of a logic of question and answer, but unfortunately never elaborated

it systematically. He clearly saw that … we can understand a

text only when we have understood the question to which it is

an answer. (Gadamer, 2004, p. 363)

[BACK]

2)

As I found out after writing the original working paper (Ulrich,

1998a), the phrase "death of the expert" is not mine. White

and Taket (1994) had used it before. By the time I prepared

the expanded version of the essay for Systems Research and

Behavioral Science (Ulrich, 2001a), I had become aware of

their earlier use of the phrase and accordingly gave a reference

to it. My discussion here remains independent of theirs, but

I recommend readers to consult their different considerations

as well.

[BACK]

3)

We'll return to this issue under the heading of "methodological

pluralism" below. For a systematic account and critique of the identification

of critical practice with methodology choice in this strand

of critical systems thinking (CST), see Ulrich (2003) and the

ensuing discussions in several subsequent "Viewpoint"

sections of the journal. Readers

not familiar with CST may find Ulrich (2012e or 2013b) useful

preparatory reading. [BACK]

4)

I have given an extensive critical account of Weber's notion

of "value-free" interpretive social science and his

underlying conception of rationality elsewhere, see Ulrich (2012b).

We will return to Weber's "interpretive social science"

in the section on theory and practice below. [BACK]

5)

I use the term "boundary critique" as a convenient

short label for the underlying, more accurate concept of a "critical employment

of boundary judgments." The latter is more accurate in

that it explicitly covers two very different yet complementary

forms of "dealing critically with boundary judgments."

It can be read as intending both a self-reflective

handling of boundary judgments (being critical of one's own

boundary assumptions) and the use of boundary

judgments for critical purposes against arguments that do not

lay open the boundary judgments that inform them (arguing critically

against hidden or dogmatically imposed boundary assumptions).

By contrast, the term "boundary critique" suggests

active criticism of other positions and thus, as I originally

feared, might be understood only or mainly in the second

sense. While this second sense is very important to me, the

first sense is methodologically more basic and must not be lost.

I would thus like to make it very clear that I always intend

both meanings, regardless of whether I use the original full

concept or the later short term.

Terms do not matter so much

and represent no academic achievement by themselves, only the

concepts or ideas for which they stand do and these should accordingly

be clear. The concept of a critical employment of boundary judgments

in its mentioned, double meaning embodies the methodological core principle of my work

on critical systems heuristics (CSH) and accordingly can be

found in all my writings on CSH from the outset (e.g., Ulrich,

1983, 1984, 1987, 1988, 1993, etc.). Only later, beginning in

1995, I have introduced the short label "boundary critique"

(see, e.g., Ulrich, 1995, pp. 13, 16-18,

21; 1996a, pp. 46, 50, 52; 1996b, pp. 171, 173, 175f; 1998b,

p. 7; 2000, pp. 254-266; and 2001, pp. 8, 12, 14f,

18-20, 24). Meanwhile I have increasingly come to find it a

very convenient label indeed, so long as it is clear

that both meanings are meant (and in this sense I use it as

a rule). Accordingly I am now employing it

regularly and systematically (cf., e.g., Ulrich, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2006a,

2012 b, c, d; 2013b; and most recently,

2017).

[BACK]

6)

The boundary questions presented here are formulated so that

the second part of each question defines the boundary category

at issue. For introductions of varying depth and detail to the boundary

categories and questions of CSH, see, e.g., Ulrich, 1983, esp. pp. 240-264; 1984,

pp. 333-344; 1987, p. 279f; 1993, pp. 594-599; 1996a, pp. 19-31,

43f; 2000, pp. 250-264; 2001a, pp. 250-264; and 2001b, pp. 91-102.

On CSH in general, as well as the way it informs my two research

programs on "critical systems thinking (CST) for citizens"

and on "critical pragmatism," also consult:

Ulrich 1988, 2000, 2003, 2006a, b, 2007a, b, 2012b, c, d, 2013b,

and 2017, and Ulrich and Reynolds, 2010.

[BACK]

7)

I should note that strictly speaking, observer-independence

does not imply that objects are non-constructed; it only implies

transferability in the sense of the above-mentioned requirement

of conventional high-quality observations. I understand de Zeeuw's

language as referring to ideal types of "objects" only, ideal

types that may help us understand the historical and present

development of science but which do not necessarily exist as

such in the actual practice of science. Nor would I equate them

with philosophically unproblematic notions of scientific objects.

The notion of "non-constructed objects" in particular

appears to be tenable only within a philosophically uncritical

realism or empiricism. On more critical grounds, it would appear

that all objects are constructed; indeed, even the celestial

bodies of astronomy are constructed as "stars," "moons,"

"solar systems," "constellations," "comets,"

etc., before they are conceptually subsumed under one or several

classes of celestial objects. Taking the example of "comets,"

they were not always construed as celestial bodies but earlier

were seen as phenomena of the atmosphere, a change of conception

that betrays the constructive side of objects.

[BACK]

8)

I have discussed de Zeeuw's ideas and the way I relate them

to my work on CSH in a bit more detail in Ulrich, 2012a. Basically,

I see in the two frameworks two complementary approaches to

the need for extending and developing the contemporary concepts

of science and research practice. [BACK]

9)

The concepts of a "critical turn" of our understanding

of competence, professionalism, rationality, and so on, and,

related to it, of securing at least a "critical solution"

to the problems of reason (particularly the unresolved problem

of practical reason and the impossible quest for comprehensiveness

or "systems rationality"), are as fundamental to my

work on critical heuristics, critical systems thinking for citizens,

reflective practice, and critical pragmatism as is the concept

of boundary critique (cf. note 5 above). See, e.g., Ulrich,

1983, pp. 20f, 36, 153-157, 176f, 222-225, 265f and passim; 1993, p. 587;

1996, p. 11f; 2001, pp. 8, 11, 14f, 20, 22-25; 2003, p. 326f;

2006a, pp. 53, 57, 70f, and 73-80; 2007a, pp. 1112, 1114; 2012c,

pp. 1237, 1244; and 2012d, pp. 1313-1316, 1318, 1320). [BACK]

10)

The following short account of the history of thought on the

mediation of theory and practice (or science and politics) is based on my earlier, more substantial

discussion of "The Rise of Decisionism" in Critical

Heuristics (Ulrich, 1983, pp. 67-79). Readers who wish I

had provided a more detailed account here in the present essay

should consult that earlier text. In addition, a classical essay

on the topic that I recommend, and which has strongly influenced

by thinking on the matter, is "The scientization of politics and public opinion"

by Jurgen Habermas in his Toward a Rational Society (see

Habermas, 1971, pp. 62-80). [BACK]

|

|

|

|

|

References (for Parts

1 and 2)

Note:

The number of references listed in this bibliography to

my own writings may suggest a lack of modesty that is not intended.

It is motivated by the circumstance that this essay is of a

didactic nature and that my teaching has always been based mainly

on my own writings, as these are the ideas I can convey to the

students in the most authentic and reflecting ways. As I hope

the essay shows, no disregard for the ideas of other writers

is intended; quite the contrary, it seeks to document its sources

by providing the most relevant and accurate references of which

I am aware, sources that have influenced me but also have been

playing a seminal role in the history of ideas concerned.

Aristotle

(1981). The Politics. Transl. by T.A. Sinclair, rev.

by T.J. Saunders. London: Penguin (orig. ed. 1962).

Aristotle

(1985). Nicomachean Ethics. Translated, with Introduction,

Notes, and Glossary, by Terence Irwin. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Churchman,

C.W. (1968). Challenge to Reason. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Churchman,

C.W. (1982). Thought and Wisdom. Seaside, CA: Intersystems.

Collingwood,

R.G. (1939/1978). An Autobiography. With an Introduction by

Stephen E. Toulmin. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1978

(orig. 1939, without Introduction).

Collingwood,

R.G. (1946). The Idea of History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University

Press.

Gadamer,

H.G. (2004). Truth and Method. Rev. 2nd edn., London and New

York: Continuum (orig. 1975, 2nd edn. 1989; German orig. 1960,

4th edn. 1975).

Habermas,

J. (1971). The scientization of politics and public opinion.

In J. Habermas, Towards a Rational Society: Student Protest,

Science, and Politics, Boston,

MA: Beacon Press, Ch. 5, pp. 62-80.

Habermas,

J. (1979). What is universal pragmatics? In J. Habermas, Communication

and the Evolution of Society, Beacon Press, Boston, Mass., pp.

1-68.

Habermas,

J. (1984-87). The Theory of Communicative Action. 2 vols. (Vol.

1, 1984; Vol. 2, 1987). Boston, MA: Beacon Press, and Cambridge,

UK: Polity.

Jackson,

M.C. (1987). Present positions and future prospects in management

science. Omega, International Journal of Management Science,

15, No. 6, pp. 455-466.

Jackson,

M.C. (1990). Beyond a system of system methodologies. Journal

of the Operational Research Society, 41, No. 8, pp.

657-668.

Jackson,

M.C. (1991). Systems Methodology for the Management Sciences.

Wiley, Chichester.

Jackson,

M.C. (1997). Pluralism in systems thinking and practice. In

J. Mingers and A. Gill, eds., Multimethodology, Wiley, Chichester,

UK, pp. 237-257.

Jackson,

M.C. (1999). Toward coherent pluralism in management science.

Journal of the Operational Research Society, 50, No.1,

pp. 12-22.

Kant,

I. (1783). Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics. 1st

edn., transl. by P. Carus, rev. edn. by L.W. Beck. New York: Liberal

Arts Press, 1951.

Kant,

I. (1787). Critique of Pure Reason. 2nd edn., transl.

by N.K. Smith. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1965.

Kant,

I. (1788). Critique of Practical Reason and Other Writings

in Moral Philosophy. Transl. and ed. by L.W. Beck. Chicago,

IL: University of Chicago Press, 1949.

Linstone,

H.A. (1984). Multiple Perspectives for Decision Making.

New York: North-Holland.

Linstone,

H.A. (1989). Multiple perspectives: concept, applications, and

user guidelines. Systems Practice, 2, No. 3, pp. 307-331.

Midgley,

G. (1992). Pluralism and the legitimation of systems science.

Systems Practice, 5, No. 2, pp. 147-172.

Midgley,

G. (1997). Mixing methods: developing systemic intervention.

In

J. Mingers and A. Gill, eds., Multimethodology, Wiley, Chichester,

UK, pp. 249-290.

Mingers,

J., and Brocklesby, J. (1996) (eds.). Multimethodology: Towards a framework

for critical pluralism. Systemist, 18, 101-132.

Mingers,

J., and Gill, A. (1997) (eds.). Multimethodology: The Theory and Practice

of Combining Management Science Methodologies. Chichester, UK:

Wiley.

Oliga,

J.C. (1988). Methodological foundations of systems methodologies.

Systems Practice, 1, No. 1, pp. 87-112.

Ormerod,

R. (1997). Mixing methods in practice: a transformation-competence

perspective. In

J. Mingers and A. Gill, eds., Multimethodology, Wiley, Chichester,

UK, pp. 29-58.

Peirce,

Ch.S. (1878). How to make our ideas clear. In Ch. Hartshorne and P. Weiss, eds.,

Collected Papers,

Vol. V., Harvard Univ.

Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2nd ed. 1969, pp. 248-271.

Popper, K.R. (1959). The Logic of Scientific

Discovery. London: Hutchinson. New edn. London: Routledge,

2002 (German orig. 1935).

Popper, K.R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations:

The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul.

Popper, K.R. (1972). Objective Knowledge: An

Evolutionary Approach. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Singer,

E.A. Jr. (1957). Experience and Reflection (C.W. Churchman,

ed.). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Strawson,

P.F. (1964). "Truth." In G. Pitcher, ed., Truth,

Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, pp. 32-53.

Toulmin,

S.E. (1978). Introduction. In R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of

History, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. ix-xix.

Toulmin, S.E. (2003). The Uses of Argument.

Updated edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (orig.

1958).

Ulrich,

W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social Planning: A New

Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern, Switzerland, and

Stuttgart, Germany: Paul Haupt. Pb. reprint edn.,

Chichester, UK, and New York: Wiley, 1994 (same pagination).

Ulrich,

W. (1984). Management oder die Kunst, Entscheidungen zu treffen,

die andere betreffen. Die Unternehmung, Schweizerische

Zeitschrift für betriebswirtschaftliche Forschung und Praxis

/ Swiss Journal of Business Research and Practice, 38,

No. 4, pp. 326-346.

Ulrich,

W. (1987). Critical heuristics of social systems design. European

Journal of Operational Research, 31, No. 3, pp. 276-283.

Reprinted in M.C. Jackson, P.A. Keys and S.A. Cropper, eds.,

Operational Research and the Social Sciences, New York:

Plenum Press, 1989, pp. 79-87, and in R.L. Flood and M.C. Jackson,

eds., Critical Systems Thinking: Directed Readings, Chichester,

UK, and New York: Wiley, 1991, pp. 103-115.

Ulrich,

W. (1988). Systems thinking, systems practice, and practical

philosophy: a program of research. Systems Practice, 1,

No. 2, pp. 137-163. Reprinted in R.L. Flood and M.C. Jackson, eds., Critical

Systems Thinking: Directed Readings, Chichester, UK, and

New York: Wiley, 1991, pp. 245-268.

Ulrich,

W. (1993). Some difficulties of ecological thinking, considered

from a critical systems perspective: a plea for critical

holism. Systems Practice, 6, No. 6, pp. 583-611.

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1993.pdf

(post-publication version of 2006)

Ulrich,

W. (1994). Can

we secure future-responsive management through systems thinking

and design? Interfaces,

24, No. 4,

1994, pp. 26-37). Rev. version

of 20 March 2009 (last updated 14 Dec

2009) in Werner Ulrich's Home Page, Section

"A Tribute to C. West Churchman."

[HTML]

http://wulrich.com/frm.html

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1994.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (1995). Critical Systems Thinking for Citizens: A Research

Proposal. Research Memorandum No. 10, Centre for Systems

Studies, University of Hull, Hull, UK, 28 November 1995.

Ulrich,

W. (1996a). A Primer to Critical Systems Heuristics for Action

Researchers. Hull, UK: Centre for Systems Studies, University

of Hull, Hull, 31 March 1996.

Ulrich,

W. (1996b). Critical systems thinking for citizens. In R.L.

Flood and N.R.A. Romm, eds., Critical Systems Thinking: Current

Research and Practice, New York: Plenum, pp. 165-178.

Ulrich, W. (1998a). If

Systems Thinking is the Answer, What is the

Question? Working

Paper No. 22, Lincoln School of

Management, University of Lincolnshire & Humberside (now University

of Lincoln), June

1998.

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1998b.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (1998b). Systems Thinking as if People Mattered: Critical

Systems Thinking for Citizens and Managers. Working Paper

No. 23, Lincoln School of Management, University of Lincolnshire

& Humberside (now University of Lincoln), Lincoln, UK, June

1998.

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1998c.pdf

Ulrich, W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil

society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective

Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713693151

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2000a.pdf

(prepublication version)

Ulrich, W. (2001a). The quest for competence in

systemic research and practice. Systems Research and Behavioral

Science, 18, No. 1, pp. 3-28.

[PDF] https://www.academia.edu/10634401/The_quest_for_competence...

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001a.pdf

(prepublication version, open access)

Ulrich,

W. (2001b). Critically systemic discourse. A discursive approach

to reflective practice in ISD, Part 2. Journal of Information

Technology Theory and Application, 3, No. 3, pp. 85-106.

[HTML]

http://aisel.aisnet.org/jitta/vol3/iss3/10/

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001c.pdf

(orig. edn., author's copyright)

Ulrich,

W. (2002). Boundary critique. In H.G. Daellenbach and R.L. Flood,

eds., The Informed Student Guide to Management Science,

London: Thomson, 2002, pp. 41-42.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/boundary_critique.html

(postpublication version)

Ulrich,

W. (2003). Beyond methodology choice: critical systems thinking

as critically systemic discourse. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 54, No. 4, pp. 325-342.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601518

(restricted access)

Ulrich,

W. (2004). C. West Churchman, 1913-2004. Obituary. Journal

of the Operational Research Society, 55, No. 11, pp.

1123-1129.

Ulrich,

W. (2006a). Critical pragmatism: a new approach to professional

and business ethics. Interdisciplinary Yearbook of Business

Ethics, Vol. 1, ed. by L Zsolnai. Oxford, UK, and Bern,

Switzerland: Peter Lang, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich,

W. (2006b). A plea for critical pragmatism. (Reflections on

critical pragmatism, Part 1). Ulrich's Bimonthly, September-October

2006.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2006.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_september2006.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2006c). Rethinking

critically reflective research practice: beyond Popper's critical

rationalism. Journal of Research

Practice, 2, No. 2, 2006, Article P1.

[HTML]

http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/64/63

[PDF] http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/64/120

or

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2006k.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2007a). Philosophy for

professionals: towards critical pragmatism. Journal of the

Operational Research Society, 58, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1109-1113.

Rev. postpublication version in Ulrich's Bimonthly, March-April

2016 (Reflections on Critical Pragmatism, Part 7).

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_march2016.html

(rev. postpublication version)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_march2016.pdf

(rev. postpubl. version)

Ulrich,

W. (2007b). The greening of pragmatism (iii): the way ahead.

(Reflections on critical pragmatism, Part 6). Ulrich's Bimonthly,

September-October 2007.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2007.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_september2007.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2009a). Reflections

on reflective practice (6a/7): Communicative

rationality and formal pragmatics – Habermas 1. Ulrich's

Bimonthly, September-October 2009 (7 September 2009).

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2009.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_september2009.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2009b). Reflections