|

|

|

The

problem of boundary

judgments1) All claims to knowledge, rationality,

and improvement depend on assumptions about what "facts"

and "values" are to be considered and what others

are to be left out. As they define the boundaries of the "problem,"

that is, the issue or situation taken to be relevant, I call

these assumptions boundary judgments. I also describe

them as "justification

break-offs," for they mark the point at which justification

ends; or as "contextual assumptions," for they can

help us understand the context that matters. The three concepts find a common

explanation

in systems theory: whenever we conceive of some part

of reality in terms of a whole of interdependent

circumstances, we need to make

prior assumptions about what belongs to it,

or more accurately, what should be considered as part

of the system and what should not. However, if you are not familiar

with systems thinking or prefer not to use its language,

it should be clear that the problem of boundary judgments poses

itself quite independently. It is not an artifact of systems

thinking or its language but represents a basic problem of all rational

thought, inquiry, and practice. Simply replace the term "system"

by "situation" or "issue" (or other suitable

terms that are used in your field of interest) to get the idea.

Boundary

judgments and the interdependence of fact and values

The important point about boundary judgments is that they

are always in play, whether we are aware of them or not. So

the question is not whether we rely on boundary judgments but rather, how

carefully we identify and examine them, so as to understand

the ways in which they condition our findings and conclusions. Since

there is no such thing as perfect boundary judgments – perfect

boundary judgments would be those we can avoid – the crucial

issue is not so much what they are but how we handle them. We

cannot avoid the deficits of knowledge and rationality they

imply; but we can at least try to handle these deficits in transparent

and prudent ways. (Laying open value implications in professional

practice would be an example of transparence; applying the precautionary principle

may illustrate the quest for prudence in fields such as applied

ecology, technology assessment, and public health.) The

important point is to keep our boundary judgments open to critique

and revision. How do they

condition the "facts" (relevant circumstances) and

"values" (needs, interests, and aims) we take to be

relevant? How to they shape the "problem" or issue

that we are dealing with in the first place? How different might

things look if we revise them in various ways?

As

a rule, the issues we face or problems we try to solve, and the answers

or solutions we come

up with, are rarely more adequately defined than are the underlying boundary

judgments. In the language of problem solving, boundary judgments

imply assumptions as to whose needs and interests should be served in the

first place, who should be involved, and what circumstances

or aspects of the real world should be part of the definition

of "the" problem.

Different boundary judgments make us see

the world differently. Accordingly, different boundary assumptions

will lead to different problem definitions, to different selections

of relevant "facts" and "values," and accordingly

also to different solutions.

But

there is a second, perhaps even more important implication of

the inevitability of boundary judgments. They not only shape people's "facts" and "values," their

"problems"

and "solutions," they also explain the way facts and

values are mutually dependent. Each time we consider new "facts," we

have implicitly changed our boundary judgments about what's

part of the picture and what is not, so that the relevant considerations

of value are also bound to change or in any case are in need

of revision. Conversely, new or revised value judgments imply

a change of boundary judgments, which may compel us to consider

new facts or can make the considered facts look different. Each

time our judgments of fact change, our value judgments are thus

bound

to change as well. We have here a precise explanation of

the interdependence of facts and values, an interdependence

that is often asserted but rarely explained in precise

terms (if at all). Bringing in the concept of boundary judgments as a mediating

third allows us to better understand how facts and values

condition one another.

Critical

systems thinking If there is a field of thinking

that you might expect to have long since dealt systematically

with the methodological implications of boundary judgments, it would surely be systems thinking, given that

it is specializing on the use of "systemic"

or integrative, inter-

and transdisciplinary approaches to research

and professional practice. Systems thinking has brought forth many

specialized subdisciplines such as systems theory (including,

e.g., general

systems theory, complexity science, cybernetics, biological systems theory, and

social systems theory),

applied systems thinking or systems research (i.e., the empirical

study of systemic aspects of the real world, e.g., applied systems

analysis and systems design, operational research, information

systems design, etc.), and systems methodology (i.e.,

the development of methodological frameworks and tools for applied

systems thinking, so-called systems methodologies). You would expect that these fields

know how to handle boundary judgments well and can provide us

with widely used and proven frameworks for

boundary analysis and critique. You would be wrong!

Boundary critique

is in fact a latecomer to the field of systems thinking. Only slowly the idea

has begun to receive the attention

it requires, supported by the emergence of what is now called

critical systems thinking (CST; for a concise, up-to-date

introduction, see Ulrich, 2012c and 2013; for advanced study,

consult 2012a, b). A main reason may be that with very few

exceptions (CST being the major example), the mentioned subdisciplines

have long struggled to free themselves

of the naturalistic, not to say positivist paradigm of science

that stood at their beginning; this paradigm makes it difficult

to deal with the implications of boundary judgments, notably

with their normative implications (i.e., the difficulty

that they are not objectively given but involve value

judgments).

A

related reason may be that the need for systematic boundary

critique is bad news, of course, for all those researchers and

professionals who are looking for clean, objective and scientific

problem definitions and solutions. They will not, as a rule,

like the idea of a "critical" systems approach

(first proposed and systematically outlined in Ulrich, 1983) but will

prefer to do

without it. It is not helpful, they will say, for it only causes

us new problems. But this is not a particularly good argument;

for it implies that the difficulty is caused

by the systems idea. Yet the systems idea is merely the messenger

that brings us the bad news. Accusing the messenger, as an

age-old tradition has it, of causing

the bad news, so as to have an excuse for ignoring it, is convenient but

won't really help in handling the problem of boundary judgments

(Ulrich, 1981, and 1983, p. 225).

The

language of selectivity Perhaps a better idea

is to take the messenger seriously and to understand boundary

critique as an opportunity to confront a fundamental difficulty

that has always been

there and will always remain a crux in the quest for valid claims

to knowledge, rationality, and improvement – the mentioned,

unavoidable selectivity of all such claims. But what

exactly is the connection between boundary critique and selectivity?

Does it really make sense, readers may wonder, to locate all

selectivity of claims in underlying boundary judgments? Indeed

it does. As I explained on an earlier occasion:

Boundary

judgments are the perfect target for this purpose, for unlike

what one might think at first, they reflect a claim’s entire

selectivity regarding both its empirical or normative content.

It is important to understand that boundary judgments are not

just one (perhaps even minor) among many other sources of selectivity

– for example, in the sense that once the reference system is

determined, it is then the specific content of our thinking

or discussion which determines how "partial" they

are. Rather, any partiality can and needs to be understood

as amounting to boundary judgments; for any content we do or

do not consider, and the way we consider it, implies corresponding

boundary judgments.… We cannot meaningfully talk about any aspect

of a situation or an issue without implying boundary judgments.

[Hence] the argumentative quality of

a reflection or discussion reflects itself in boundary judgments.

Wanting argumentation, say because we argue incoherently

or fail to anticipate side effects and risks of a proposed action

correctly, always amounts to modifications of the reference

system that we treat as relevant. Thus, if for example we consider

some aspect as relevant and perhaps even agree with others that

it is important, but then fail to take it properly into account,

due to lacking knowledge, to an error of judgment or some communicative

misunderstanding or distortion, we have in fact excluded that

aspect from our reference system. (Ulrich,

2005, p. 3)

Boundary

judgments, then, are indeed a good leverage point for examining

selectivity. Without such an effort, selectivity

risks becoming a source of bias, partiality, and failure. The

good news is that since systems ideas meanwhile play a role in many

fields of research, boundary

critique is now increasingly recognized as an important methodological principle of

sound inquiry and practice. This holds true particularly for

a growing number of applied disciplines;

among them (to mention just a few) operations research and management

science, the design fields, public policy and planning theory, environmental planning and management,

social planning, development studies, technology assessment, evaluation research,

professional education and ethics, and many others.

Critical

systems heuristics, or facing the bad news Critical systems

heuristics, or shorter critical heuristics (CSH; see Ulrich, 1983,

1987), proposes a practical

framework that should help

us to deal with the bad news. The framework is grounded in systems

thinking along with practical philosophy, the philosophical

study of what good or proper practice and rational discourse

about it mean. (Well-known examples are American pragmatism

and the practical philosophies of Aristotle and Kant, all of

which play a role in CSH.) This theoretical grounding does not mean we all need now

to speak systems jargon or study philosophy. Once we have listened

to the bad news and understood its message, it is not so important

what language we speak but only that we take the message seriously.

Thus, in critical heuristics I often use everyday terms such

as "problem" or "problem situation" along

with more precise, theoretically grounded terms such as "reference

system"

or "context of application," instead of merely or

mainly using systems language, for example, by speaking of "systems"

of

interest or of concern, or (to avoid the trap of reifying systems as if they were real entities) of "systems maps

and designs."

The basic idea remains

the same: in order to reflect systematically

about what we know and should do about a situation of concern

– that is, more precisely, how we should assess related claims

to knowledge, rational action, or proposals for improvement

– it is never a bad idea to

surface the underpinning boundary judgments and to trace their

live practical implications for the different parties concerned, as

well as to systematically modify them and to check how different

the claims under consideration then look. A very good systems map

or

design should make its underlying

boundary judgments explicit and, in the case of a design, should also

point out how its concept of

"improvement" might look different if alternative

boundary judgments were chosen.

The

emancipatory use of boundary judgments But not all designs

are very good

designs. Hence it is important that ordinary people be enabled

to challenge systems designs or proposals for action of concern

to them, by learning to make visible to themselves and to others

the ways in which they depend on boundary judgments. This is

possible in principle, due to the fact that when it comes to

boundary judgments, there are no definitive experts. In respect

to these judgments, those who have the advantage of knowledge

and status or power on their side are just as much lay people as anyone

else. Or, to say it more bluntly, when it comes to debating

boundary judgments, experts do not look good. Nor do decision

makers, usually. Citizens, once they have got the idea, have

a real chance to be just as competent as those who "know

better" and to influence the way designs or proposals for

action look. This provides us with a crucial leverage point

for what I call emancipatory boundary critique, that

is, for giving a competent voice to ordinary citizens with respect

to boundary judgments (for introductory readings, see Ulrich,

1993, 1996, and 2000; for advanced study, consult Ulrich, 1983, Ch. 5).

The question is, how

can we identify and discuss boundary judgments systematically?

This is where the principle of "systemic triangulation"

and its underlying concept of the "eternal triangle"

come in.

|

1) This section, except the quote it includes from Ulrich, 2005,

is a revised and extended extract from Ulrich, 1996, pp. 15-19.

|

|

|

|

The

eternal triangle2)

As we have understood by now, the concept of boundary judgments says that both the

meaning and the validity of a claim depend on how we bound the reference

system, that is, the situation or context that matters when

it comes to assessing the claim's merits and defects. On this

reference system in turn depend the facts and values we consider

in this assessment. We are facing an iterative movement of thought

in which the reference system considered (i.e., the boundary

judgments underpinning it), and the judgments of fact and value

applied to it (i.e., the selection of relevant circumstances)

mutually shape one another. The moment we change our boundary

judgments, the facts and values that matter will change as

well. For example, if we expand the system boundaries, new facts

come into the picture. But then, new facts can in turn make

us revise some of our boundary judgments. For example, if we

learn of previously unknown long-term effects of a proposed

action, we may want to extend the time horizon we consider so

as to sweep in those anticipated long-term effects (a

boundary judgment with respect to the relevant part of the future).

Changing the time horizon in turn may compel us to adjust

our value judgments (e.g., our sense of responsibility for

future generations), which then may again make the relevant

facts look different,

and so on. Thus boundary judgments strongly influence the way

we "see" a situation.

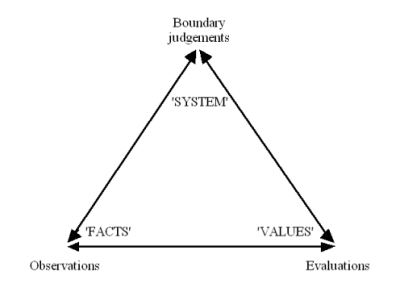

Since boundary judgments ("the

system"), observations ("the facts"), and evaluations

("the values") are so closely interdependent, they form what

I call an eternal

triangle – the eternal triangle of boundary critique (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: The eternal

triangle of boundary critique: the interdependence of boundary judgments, observations,

and evaluations

The

facts we observe, and the ways we evaluate them, depend on how

we bound the system of concern. Different value judgments can

make us change boundary judgments, which in turn makes the

facts look different. Knowledge of new facts can equally make

us change boundary judgments, which in turn makes previous

evaluations look different, etc. (Sources: Ulrich, 1998, p. 6;

2000a, p. 252; 2000b, p. 18f; 2002, p. 41f; and 2003, p. 334)

The

triangle illustrates the

dependence of both "facts" (relevant observations) and

"values’

(relevant evaluations) on the reference "system" (boundary

judgments) and thereby, as we have noted, also explains the fundamental interdependence

of judgments of fact and value, namely, via boundary judgments. The

triangle figure offers itself since figuratively speaking, each angle in a triangle depends on the

other two. We cannot modify any one without

simultaneously modifying the other two.

It

is a case of what the French call a ménage à

trois. As

everybody knows, mutual understanding can be difficult under

such circumstances. Differing boundary judgments make it difficult for people to communicate. Unfortunately, many

people do not appreciate the role that their boundary judgments play. As the concept is unknown to them, they suspect

the reason of mutual disagreement is that the other parties

got their facts wrong or rely on dubious ethical principles.

So they quarrel about statistics and ideologies. Because I am

right, the others must be wrong. Because I am responsible, the

others must be irresponsible. Because I am rational, the

others must be irrational. Because I am compelling, the others

must be idiots!

That

may sometimes be true, but more often the crucial difference

lies in differing reference systems. So long as the involved

parties do not see that they talk about different reference

systems, they will not really understand each other. In fact

it is quite rational that they do not. How could they reasonably

see the same facts and rely on the same value judgments, since

they are talking of different issues?

Instead

of disputing the other parties’ facts and values, it might then

be more fruitful to uncover the different systems of concern.

Once we begin to appreciate each other’s reference systems,

we can usually understand much better why our opinions differ.

Perhaps we can even agree about the reference system on which

we want to talk, at least in the sense that we focus on one

at a time. But

even if we cannot agree on such a coordinated handling of the

situation, we can at least appreciate one another’s

different rationalities.

We need not agree in order to understand why we do not.

|

2) This section is an edited extract from Ulrich, 2000a, p. 251f;

a similar account can also be found in Ulrich, 2003, p. 334.

|

|

|

|

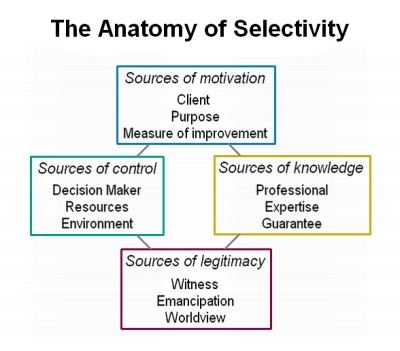

The

anatomy of selectivity The eternal triangle

is useful to explain – and remind us at all times – why reflective

practice of inquiry and professional intervention calls for

a systematic process of uncovering and examining the boundary

judgments that inform all our conjectures, findings and conclusions.

For this purpose critical systems heuristics (CSH) offers a table of twelve basic

boundary categories and, derived from it, a checklist of twenty-four

boundary questions. It also offers a small selection of what

I call "critically-heuristic

ideas," that is, essential general ideas such as the systems

idea, the moral idea, and the guarantor idea, along with a few complementary ideas such as the participatory idea, the

emancipatory idea, and the democratic idea, all of which can serve

as standards for reflection on the answers we give to boundary

questions. For the present purpose it is not necessary to explain

these boundary categories, questions, and ideas in any detail; interested

readers will find accounts in many of my publications (see, e.g.,

Ulrich 1983, 1987, 1993, 1996, 2000a, 2001, and 2013).

Instead, it is quite sufficient

to have a basic notion of the anatomy of selectivity –

the basic types of boundary issues – that

the boundary questions aim to make a subject of scrutiny and

discussion. Once these basic boundary issues are understood,

it does not matter how exactly we formulate the boundary categories

and questions; it will often make sense to adapt them to the

specific field of practice concerned. Here is a basic scheme,

in a language that should be relevant for many applied disciplines (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: The anatomy

of selectivity

There

are four basic boundary issues, each of which stands for a basic

source of selectivity in research and professional practice.

They are asking for a claim's sources of motivation, of control,

of knowledge, and of legitimacy. Each boundary issue is covered

by three types of boundary categories that ask for the major

group of stakeholders concerned, for this stakeholder group's

major concern, and for the crucial issue or related methodological

crux in need of clarification, respectively. The boundary questions

are so formulated that they also define the intent of the four

basic boundary issues / sources of selectivity, as well as of

the twelve boundary categories. (Source: derived from a representation

of the overall architectonic of critical systems heuristics in

Ulrich, 1983, p. 342; the present, simplified figure has

not been published as yet)

I

call the reflective or discursive process of uncovering a claim's

specific anatomy of selectivity boundary

critique (the general term for a reflective or discursive

approach) or also boundary discourse (the more specific

term for a dialogical approach). As explained above, I like

to describe this process with the

imagery of the eternal triangle; based on this imagery, I then

also explain boundary critique as a process

of systemic triangulation, that is, a systematic effort

of thinking through the eternal triangle.

|

|

|

|

|

The

concept of systemic

triangulation

Since antiquity it was known that there

exists a fixed relationship between the sides and the angles

of a right-angle triangle, so that if two elements (say, the

value of one of the two acute angles and the length of at least

one side) are known, all sides and angles can be calculated.

This happens by means of mathematical functions that describe

these relationships, the so-called "trigonometric functions"

(sine, cosine, and tangent). This knowledge

was used for surveying land, that is, measuring distances between

triangulation points or determining their locations. The term triangulation

originally

means the use of several (at least three) triangulation points to

this end, so that the principles of trigonometry could be applied.

In modern

times, this old idea of triangulation became a metaphor for

the use of more than one data basis for testing theoretical

hypotheses and conversely, for validating and interpreting data

in the light of alternative theories or perspectives. Particularly

in the empirical social sciences, the principle of triangulation

has

thus come to demand reliance on multiple perspectives and data

bases, the latter gained by alternative research methods, to describe and analyze social

issues; a seminal contribution is by Denzin (1970).

As

a practicing evaluation researcher, the principle of triangulation

was familiar to me; but only eventually, after starting to describe

boundary critique in terms of the "eternal triangle,"

it occurred to me that a useful way to understand boundary critique

was indeed by conceiving of it as a different, richer concept

of triangulation. The eternal triangle made it plain that the

conventional concept of triangulation, as used in the social

sciences, was insufficient in that it focused on the generation

of factual knowledge while at best affording a marginal role

to value judgments and entirely neglecting the role of boundary

judgments. Once I had made this connection between the eternal

triangle and scientific triangulation, it was only a small further

step to propose a systematic principle of systemic triangulation. In

fact, as I recognized with hindsight, I had proposed and applied

it all along, just without designating it as such! "Systemic

triangulation"– a term first used in Ulrich, 2000b, p. 18f,

and 2003, p. 334, but implicit in all references to the

eternal triangle – goes beyond the conventional concept of triangulation

by considering not only different data sets and corresponding

theories and research methods as bases for judgments of fact but

also different normative assumptions (judgments of value) and

different

reference systems (boundary judgments); in this way it is a

tool for gaining a deeper understanding of a claim's anatomy

of selectivity, including supposedly merely factual claims.

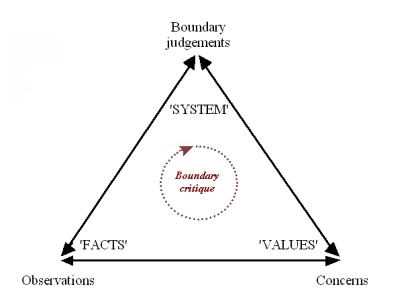

Once

we have understood the idea, systemic triangulation can also

be described more simply as the reflective or discursive process

by which the eternal triangle is applied to specific issues

(Fig. 3). It is a core skill we need to develop in order

to become competent in boundary critique.

Fig. 3: Systemic

triangulation: the process of boundary critique

Systemic

triangulation is the reflective or discursive process of systematically

applying the "eternal triangle" to the task of boundary

critique. As a new methodological principle, systemic triangulation

extends the conventional concept of triangulation in science by

considering findings and conclusions not only in the light of

multiple observations (judgments of fact relying on different

research methods, theories, and data bases) but also of different

ethical and moral perspectives (value judgments as to relevant

concerns and notions of improvement) and reference systems (boundary

judgments as to relevant situations or contexts). (Sources: Ulrich, 2012b,

p. 1317; adapted from Ulrich, 1998, p. 6; 2000a, p 252;

2000b, p. 18f; 2002, p. 41f; and 2003, p. 334)

Systemic

triangulation also stands for an essential critical stance that

we need to cultivate in addition to the scientific attitude

of objectivity and suspended judgment, and/or the professional

virtue of detachment. It involves a conscious effort of "stepping back" from current

reference systems so as to appreciate the different perspectives

afforded by alternative conceivable reference systems. Such

a stance places high demands on a researcher's or professional's

ability to maintain the tension between divergent standpoints

and to suspend judgment while unfolding the views and consequences

they entail – perhaps the most distinguished competence a researcher

or professional can strive to cultivate.

With

the idea of systemic triangulation, the eternal triangle thus

suggests a useful analogy for understanding a core skill that

is conducive to systematic boundary critique, as well as a related

critical professional stance or ethic. A competent professional

will make it a personal habit to always consider

each corner of the triangle – relevant observations, concerns,

and boundary judgments – in the light of the other two, by

asking questions such as these:

- What new facts become

relevant if I expand the boundaries of my reference system

and/or modify my value judgments?

- How do my

valuations look if

I consider new facts that refer to a modified reference system,

or if I rely on the multiple perspectives that other

people have of the issue under consideration?

- In what way may my

reference system fail to do justice to the

perspectives of different stakeholder groups?

Perhaps

I may conclude this short introduction to the principle of systemic

triangulation with two quotes from earlier writings that capture

its consequences for research and professional practice (and

they are essential consequences, I think):

"Any claim that

does not reflect on the underpinning ‘triangle’ of boundary

judgments, judgments of facts, and value judgments, risks

claiming too much, by not disclosing its built-in selectivity."

(Ulrich 2002, p. 42; similarly 2003, p. 334 and 2005, p. 6)

"Systemic

triangulation is indeed highly relevant from a critical point

of view. It serves several critical ends:

- It

helps us in becoming aware of, and thinking through, the

selectivity of our claims – a basis for cultivating reflective

practice.

- It

allows us to explain to others our bias – how our views

and claims are conditioned by our assumptions. We can thus

qualify our proposals carefully, so that they gain in credibility.

- It

allows us to see through the selectivity of the claims of

others and thus to be better prepared to assess their merits

and limitations properly.

- It

improves communication, for it enables us to better understand

our differences with others. When we find it impossible

to reach through rational discussion some shared views and

proposals, this is not necessarily so because some of the

parties do not want to listen to us or have bad intentions

but more often, because the parties are arguing from a basis

of diverging boundary judgments and thus cannot reasonably

expect to arrive at identical judgments of fact and value.

And finally, as a result of all the above implications:

- It

is apt to promote among all the parties involved a sense

of modesty and mutual tolerance that may facilitate productive

cooperation; for once we have understood the principle of

systemic triangulation, we cannot help but realise that

nobody has a monopoly for getting their facts and values

right, and that accordingly it is of little help simply

to accuse those who disagree with us to have got their facts

and values wrong."

(Ulrich

and Reynolds, 2010, p. 287)

|

|

|

|

|

The

imagery of systemic

triangulation

As

we have found, the imagery of a triangle quite naturally

offers itself for depicting the idea and process of boundary

critique. It's

so obvious a metaphor, given that in a triangle we cannot change one angle without

affecting the other two, just as in boundary critique we face

three interdependent types of judgment, each of which cannot

be changed without a need for revising the other two. No matter

at which corner point of the triangle we start to change things,

we'll end up changing all three. Perhaps this

obvious implication of a ménage à

trois, as I have put it, explains why I have never found it necessary to explain the

imagery of systemic triangulation in more than cursory form.

After all, it is a mere metaphor. Rather than explaining the

metaphor, I found it important to explain the methodological

considerations for which the eternal triangle is only a metaphor.

However, it is true that the metaphor is of interest in its

own right, given that it is meant to inspire a demanding kind

of professional stance and competence. Now that the principle

of systemic triangulation is beginning to find recognition in

ever more fields, it is certainly time to dedicate more attention

to its underlying imagery.

The

present short article is intended to correct the situation a

bit. It is in fact the most extensive account I have thus far

given of the principle. The impetus for doing it came from my

appreciated colleague and Senior Lecturer at the Open University in Milton Keynes,

UK, Martin Reynolds. When a publisher requested him to ask for my permission to reproduce

the eternal triangle, he took the occasion and asked me about the origin of its imagery. "I wonder,"

he wrote, "where your diagrammatic representation may have

been inspired from (if anywhere)?" (Reynolds, 2016) I certainly

found it a question worthwhile to consider, if not a wake-up

call reminding me that I had somewhat neglected this question.

It made me reflect on my personal idea history, and discover

that there was more to it than I had assumed. I did not anticipate

then that I might publish this personal reflection one day,

but here is the answer I wrote to Martin, exactly in the wording

I sent it to him except for a few minor editorial corrections:

"Martin,

There is no figurative source of the eternal triangle of

which I would be aware. It's rather the other way round, it

was the result of a rather long personal history of ideas. As

you may have noticed, I generally like conceptualizations of

issues that work with triple categories or options. (A recent

other example is provided by my focus, in the series of explorative

essays on the role and proper handling of general ideas, on

what I identified as three key ideas of Upanishadic thought

in ancient India, atman, jagat, and brahman, with the second

one being an unusual but for me crucial addition to the other

two.)

The way to the 'eternal triangle' was like this:

First, it had slowly dawned on me that the often asserted,

but methodologically somewhat nebulous interdependence of 'facts'

(empirical judgments) and 'values' (normative judgments)

could be patently explained by adding 'systems' (boundary

judgments) as the missing link as it were. So there I was, once

again, with one of my favourite triple characterisations.

Second, one day (I remember the moment quite well, as it

was one of those rare but precious 'Aha' experiences)

it occurred to me that a triangle offered itself naturally for

depicting the interdependencies between 'facts', 'values'.

and 'systems'. It's such a convenient way to capture

the need for thinking through the three core concepts (represented

by the triangle's corners) of 'facts', 'values',

and 'systems', as well as the interdependencies – often

also tensions or conflicts – between them (represented by the

triangle's sides); thinking through, that is, both conceptually / methodologically (how

to understand and handle the issues involved) and practically

(how to formulate / unfold these issues in specific situations).

As a third and last step, the name 'triangulation'

offered itself for these processes of 'thinking through'

the eternal triangle, both in general and in specific applications.

But of course, as a former, practicing social researcher I remembered

that the concept of triangulation already had a different, rather

narrow meaning in the social sciences; it meant, in essence,

the alternative interpretation of a given set of collected data

(or findings) in the light of alternative theoretical hypotheses

(or methods), or conversely, the examination of given findings

(or hypotheses) in the light of different sets of data. I had

always sensed that something was not satisfactory with this

conventional concept of triangulation, I now knew why: because

it ignores the essential role of boundary judgments. It had,

consequently, remained a bipolar concept, looking only at the

tension between empirical findings (or data) and theoretical

assumptions

that informed them, whether in the form of theories or hypotheses

to be tested or methods. A well-understood

effort of triangulating research findings, it occurred to me,

had to include the effort of seeing / challenging them in the

light of different sets of boundary judgments (or 'reference

systems' as I also call such sets, as they serve as reference

points for assessing selectivity). The name 'systemic triangulation'

thus offered itself for this further-reaching (or deeper, if

that doesn't sound too presumptuous) concept of triangulation.

Further, since from a critical point of view, there is no natural

end (no stopping rule) for such processes of triangulation,

the figure of the triangle seemed very adequate (you can go

round and round the triangle, there is no natural end), and

so did accordingly the name I had given it, the 'eternal

triangle'.

In sum, the figure of the eternal triangle was really inspired

by the methodological conjectures that led to it, rather than by some other figurative source of which I was

aware then or would be aware today." (Ulrich, 2016)

My

conclusion from this short essay on the concept and imagery of

systemic triangulation is simple: systemic triangulation

is perhaps not a bad idea. The references that follow should help

you to inform yourself a bit more about the idea and then start

using it – the only way you can experience its heuristic usefulness

and critical force.

I hope you'll give it a try.

|

|

|

|

|

References

Denzin,

N.K. (1970). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction

to Sociological Methods. Chicago, IL: Aldine (3rd edn. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989).

Reynolds,

M. (2016). Personal communication with question on the imagery

of systemic triangulation (email message of 18 Dec 2016.)

Ulrich,

W. (1981). On blaming the messenger for the bad news. Reply

to Bryer's comments. Omega, The International Journal of

Management Science, 9, No. 1, p.7.

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0305-0483(81)90060-8

(restricted access)

[HTML] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0305048381900608

(restricted access)

Ulrich, W. (1983). Critical Heuristics of Social

Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern,

Switzerland: Haupt. Pb. reprint edn. Chichester, UK; and New

York: Wiley, 1994.

Ulrich,

W. (1987). Critical heuristics of social systems design. European

Journal of Operational Research, 31, No. 3, pp. 276-283.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0377-2217(87)90036-1 (restricted access)

[HTML]

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/03772217/31/3

(restricted access)

[HTML] http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0377221787900361

(restricted access)

Ulrich, W. (1993). Some difficulties of ecological

thinking, considered from a critical systems perspective: a

plea for critical holism. Systems Practice, 6, No. 6,

pp. 583-611.

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01059480

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://www.springerlink.com/content/v6887r245467m511

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1993.pdf

(postpublication version of 2006)

[PDF] https://www.academia.edu/11302813/Some_difficulties_of_ecological_thinking

(postpublication version of 2006)

Ulrich, W. (1996). A Primer to Critical Systems

Heuristics for Action Researchers. Hull, UK: University

of Hull Centre for Systems Studies.

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1996a.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (1998). Systems Thinking as if People Mattered: Critical

Systems Thinking for Citizens and Managers. Working Paper

No. 23, Lincoln School of Management, University of Lincolnshire

& Humberside (now Lincoln University), Lincoln, UK.

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_1998c.pdf

Ulrich, W. (2000a). Reflective practice in the civil

society: the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective

Practice, 1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/713693151

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2000a.pdf

prepublication version)

Ulrich,

W. (2000b). Critically Systemic Discourse, Emancipation and

the Public Sphere. Working Paper No. 42, Faculty of Business

and Management, University of Lincolnshire & Humberside

(now Lincoln University), Lincoln, UK.

Ulrich, W. (2001). The quest for competence in

systemic research and practice. Systems Research and Behavioral

Science, 18, No. 1, pp. 3-28.

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sres.366

(restricted access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2001a.pdf

(prepublication version)

[PDF] https://www.academia.edu/10634401/The_quest_for_competence...

Ulrich,

W. (2002). Boundary critique. In H.G. Daellenbach and R.L. Flood

(eds), The Informed Student Guide to Management Science,

London: Thomson, 2002, pp. 41-42.

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/boundary_critique.html

adapted prepublication version)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2002a.pdf

(prepublication version)

Ulrich,

W. (2003). Beyond methodology choice: critical systems thinking

as critically systemic discourse. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 54, No. 4, pp. 325-342.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601518

(restricted access)

Ulrich, W. (2005). A

brief introduction to critical systems heuristics (CSH). ECOSENSUS Publications, Knowledge Media Institute

(KMI), The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, 14

October 2005.

[HTML] http://projects.kmi.open.ac.uk/ecosensus/publications/index.html

(for download)

[PDF] http://projects.kmi.open.ac.uk/ecosensus/publications/ulrich_csh_intro.pdf

(orig. version)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2005f.pdf

(current version)

Ulrich, W. (2012a). Operational

research and critical systems thinking – an integrated perspective.

Part 1: OR as applied systems thinking. Journal of the Operational

Research Society, 63, No. 9, pp. 1228-1247.

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jors.2011.141

(restricted access)

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_july2016.html

(postpublication version, open access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2012d_prepub.pdf

(prepublication version)

Ulrich, W. (2012b). Operational research and critical

systems thinking – an integrated perspective. Part 2: OR

as argumentative practice. Journal of the Operational Research

Society, 63, No. 9, pp. 1307-1322.

[DOI]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/jors.2011.145

(restricted access)

[HTML] http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_september2016.html

(postpublication version)

[PDF]

http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2012e_prepub.pdf

(prepublication

version)

Ulrich,

W. (2012c). CST's two ways: a concise account of critical systems

thinking. Ulrich's Bimonthly, November-December 2012.

[HTML]

http://wulrich.com/bimonthly_november2012.html

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/bimonthly_november2012.pdf

Ulrich,

W. (2013). Critical systems thinking. In S.I. Gass and M.C.

Fu (eds.), Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management

Science, 3rd edn., 2 vols. New York: Springer, Vol. 1, pp.

314-326.

[DOI] http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1153-7_1149 (restricted

access)

[HTML] http://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-1153-7_1149

(restricted access)

Ulrich,

W. (2016). Personal communication to Martin Reynolds, Open University,

Milton Keynes, UK, on the imagery of systemic triangulation

(email message of 18 Dec 2016.).

Ulrich, W., and Reynolds, M. (2010). Critical systems

heuristics. In M. Reynolds and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change: A

Practical Guide, London: Springer, in association with The Open University,

Milton Keynes, UK, pp. 243-292.

|

|