|

|

|

An

"Eastern" perspective: three ancient Indian ideas

(continued) The last essay of this series,

in the Bimonthly of May-June 2015 (Ulrich, 2015b), analyzed

three selected Upanishadic ideas – the concepts of brahman,

atman, and jagat – from a mainly etymological

and methodological perspective, as distinguished from a traditional,

predominantly spiritual and metaphysical reading of the Upanishads.

Of these three ideas it was the third, jagat, which we

found to be of particular methodological interest. While brahman

and atman embody ideal conceptions of the cosmic universe and

of the individual self (or what Kant designates the "cosmological

idea" and the "psychological idea"), I take jagat (literally

= world, universe) to stand for a critically reflected, realist conception of the

world we live in. In the terms of our envisaged framework of

critical contextualism, realist notions depend on contextual

assumptions (What is the proper context to be considered

for this argument of action?), whereas ideal notions have a universalizing (i.e.,

decontextualizing) thrust (How does this argument or action

look if we take it to be adequate beyond the originally assumed

context?). A critically tenable handling of

contextual assumptions has to maintain the tension between universalizing

and contextualizing movements of thought, so as to be able to

see the deficiencies of either in the light of the other.

The

question that must interest us, then, is whether the three ideas

can be understood to support such a double movement of critical

thought. To put it differently, can we bring them into a systematic

relationship so that they would illustrate and enrich our understanding

of the cycle of critically-contextualist thinking as proposed

earlier in this series (see Ulrich, 2014b, Fig. 4)?

Seventh intermediate reflection:

The example

of the Isha Upanishad

In the two concluding essays of the series, beginning with the present Part 6, I propose we focus on the Upanishadic concept of jagat

and discuss it from a critically-contextualist perspective.

Is there an understanding of jagat that would be conducive

to critically contextualist practice, whether of research and

professional practice or of everyday practice? To examine this

question, let us turn to what may be the term's most famous

occurrence in all ancient Indian scriptures, namely, in the

first verse of the Isha Upanishad (also

called Ishopanihsad, Ishavasya Upanishad, or Vagasaneyi-Samhita

Upanishad, the latter name being the one used in Müller's

translation of 1879). It is, to my knowledge, the only

occurrence where it plays a major role in the Upanishads. But

this one occurrence is considered so important that Mahatma

Gandhi once famously remarked about it: "If all

the Upanishads and all the other scriptures happened all of

a sudden to be reduced to ashes, and if only the first verse

in the Ishopanishad were left in the memory of the Hindus, Hinduism

would live for ever." (Gandhi, 1937, p.

405)

As I see it, the Isha is also one of the Upanishads that perhaps best embody

the "dawn of philosophical reflection" to which I

referred in the introductory part of this excursion into ancient

India (see the section "The dawn of philosophical reflection:

the discovery of the knowing subject" in Part 4, Ulrich, 2014c, pp. 6-11; rev.

version, 2015a, pp. 7-13). It stands

for the idea, probably first emerging in human history with

the Upanishads, that "the power to control and change man's

destiny resides in man himself, in the ability to improve one's

individual consciousness and understanding" and hence,

that man can be the author of his own destiny, rather than just

being at the mercy of cosmic powers (gods and demons) that he cannot

control or understand. Accordingly important it became, as we

noted, "to know and discover one's inner reality, so as

to expand one's self-awareness and ultimately, to achieve spiritual

autonomy rather than devotion to cosmic forces and gods"

(Ulrich, 2014c, p. 6, and 2015a, p. 8). But of course,

this is how today we can understand the history and importance of

Upanishadic thought with hindsight, in the light of the history

of ideas that has occurred since. At that time, such revolutionary

ideas could emerge only slowly and had to be formulated in the

language and imagery of the Veda, which due to their age we must expect to cause

us considerable difficulties of translation and understanding

today. But let us see.

The first verse of the Isha

Upanishad: transliteration and translation

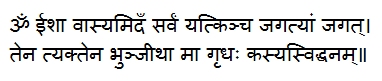

Transliteration This is how the famous first verse of the

Isha Upanishad reads in Sanskrit language, first written

in Devanagari script and then transliterated to Roman script:

(Source: Wikisource.org

)

The transliteration to Roman script reads:

om isa vasyamidam

sarvam yatkincha jagatyam jagat

tena tyaktena bhunjitha

ma grdhah kasyasviddhanam

Source: http://www.swargarohan.org/isavasya/01

(cf.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isha_Upanishad)

or, in phonetic script as also used in this essay:

om isha vasyam idam sarvam, yat kim ca jagatyaam jagat.

tena tyaktena

bhunjithaa, maa

gridha kasya svid dhanam.

(adapted from: http://sanskrit-texts.blogspot.ch/2006/05/isha-upanishad.html

)

Translation Lest

we rely on any of the traditioned translations of

the Isha's first verse without a proper notion of conceivable

options that the benefit of historical distance offers us today,

let us first gain an overview

of the rather wide range of meanings of most of the Sanskrit terms involved.

Here is a list compiled from the Sanskrit dictionaries mentioned

at the outset of this exploration of ancient Indian ideas (see

the "Sources" box in Part 4 of the series, Ulrich,

2014c or 2015a, p. 2f); the list uses short references

to these dictionaries as explained in the subsequent Legend.

om = mystical

utterance during meditation; holy word that signifies brahman

isha (or isa, isah)

= originally: possessing

strength, completely mastering, acting like a master, being

master or lord of; being capable, powerful, supreme, owning;

a master, speaker, author; speech, utterance, words; later also:

supreme being, supreme spirit, personified as the Lord, the

highest self (A393; MW169,2); able to dispose of, entitled to;

capable of; owner, lord, ruler, chief of (Mac 47)

vasya[m] = to be covered, clothed

or enveloped in, pervaded by, dwelling in (A1421, cf. 141)

ida[m] = known, present; this earthly

world, this universe; this, here (MW165,3; A383)

sarva[m] = all, every, any; whole,

entire; complete; [with negation] not any, none (A1655; B7-084;

B/addenda 360.1; also see Olivelle, 1996, p. 297 note 4.9-10);

hence the Upanishadic formula: sarvam idam brahma = "this

whole world is brahman" = all [this world] is ultimately

one

yat kim ca = what further, whatsoever,

whatever aligns itself or joins; composed of kim= what?

how? whether? etc. (indicating a question mode), ca=

further, and also, as well as, moreover (B2-065 and 2-202f,

MW282,3), and yat= to join, unite, bring into order,

align oneself (in Vedic use; otherwise also = to endeavor, strive

after, be eager or anxious for) (B5-119; A1299)

jagatya[am] = in the jagats, [moving]

in this world, on earth (A408,1; B2-246f)

jagat = world, moving, movable,

locomotive, living; that which moves or is alive, is in everybody's

sight, air, wind, earth; this world; heaven and the lower world,

the worlds, the universe; people, mankind; a field [of plants],

site [of a house], etc.; (MW408,1; A720; B2-246; cf. Table 2)

tena = so, therefore; thus, in that manner, in that direction;

on that account, for that reason (B3-042; Mac112, MW454,3 and

455,1)

tyaktena = renouncing this, it, composed of tyakt

= to derelict, abandon, leave, and ena, in Vedic use

= [a course, way] to be obtained (A5, Mac112)

bhunjitha = to enjoy, indulge,

from bhuji = embrace [cf. English "hug"], granting

of enjoyment, favor; one who grants favors, a protector, patron

(Mac203; MW203,1 and 759,2), also bhuj =

t

o enjoy, embrace, use , possess, consume; to make use of , utilize,

exploit, govern (MW

759,2), and jita = won , acquired,

conquered, subdued; overcome or enslaved by; occurring often

in compounds such as jitakopa = one who has subdued anger;

jitakshara = one who has mastered his letters, [is] writing

well; or jitamitra = one who has conquered his enemies,

[is] triumphant (MW420,3)

ma = a particle of prohibition or

negation: "no," "not," "don't,""be

not," "let there not be"; that not, lest, may

it not be; "and not," "nor" (MW 804,1f);

also 1st person pron. basis (cf. "me"); time; poison;

a magic formula (MW 771,1f); moon, measure, authority, light,

knowledge, binding, fettering, tying, death (Wil630); disturbing

(B/addenda 287.3)

gridha = desirous of , eagerly

longing for (MW361,2; cf. English "greed"); whence

ma gridha = "let there be no greediness"

kasya = whose? composed of ka-

= interrogative particle (cf. kim, under yat kim

ca), often in connection with svid) and sya = 3rd

person pron. basis (MW240,2f; MW1273,1)

svid = (a particle of interrogation

or inquiry, often implying doubt or surprise, and translatable

by "[what/who] do you think?," "can it be?"

or simply "indeed?"; also rendering a preceding interrogative

indefinite, e.g. "whoever," "whatever,"

"any [one]," "anywhere" (A1743; MW1284,3)

dhana[m] = prize [of a context, or contest itself, a thing

raced for, etc.]; wealth, riches, movable property, treasure,

capital (MW508,2; B3-140; property of any description, thing,

substance, wealth (Wil436)

Legend: The sources of translation are indicated for each

word by the following short references: A =Apte (1965/2008);

B = Böthlingk and Schmidt (1879/1928); Mac =

Macdonell (1929); MW = Monier-Williams (1899), often usefully

searched via Monier-Williams et al. (2008); and Wil = Wilson

(1819/2011). The short references are followed by page numbers

and, in the case of MW, with column numbers added after a comma.

Page numbers are useful for searching the scanned, original

layout editions that are now in the public domain and available

online of most dictionaries, as listed in the References section

of this essay.

Müller's early translation

Still influential and often cited is Müller's (1879) early

translation, which accordingly may still count as a standard

translation. It comes in two version, the original version of

1879 and a later, revised version of 2000. The original versions reads:

All this,

whatsoever that moves on earth

is

to be hidden in the Lord (Self).

When thou hast surrendered

all this,

then

thou mayest enjoy.

Do

not covet the wealth of any man.

(Isha,

1.1, as transl. by Müller, 1879, p. 311; line-breaks

and indents added)

In the revised version by Müller and Navlakha (2000), we find:

All

this, whatsoever that moves in this moving universe

is encompassed by the Self.

When thou hast surrendered

all that [i.e., the material wealth],

and

wilt seek not what others [continue to] possess,

then

thou mayest truly enjoy.

(Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Müller and Navlakha, 2000, p. 17;

the brackets are Navlakha's, the indents are mine. Note that

the phrase "surrendered all that"

stands for what in our terms should

read "surrendered all

this [material world]";

compare our earlier discussion of the metaphysics of "this"

and "that" in Part 4 of the series, Ulrich, 2014c,

pp. 11-14, rev. version Ulrich, 2015a, pp. 13-19)

While Müller originally translated jagat as "whatsoever that

moves on earth" and wavered in his translation of isha

between "the Lord" and "Self," the revision

replaces “earth” by “universe” and drops reference to “the Lord.”

This is precisely how I suggest we should understand

the two terms. “Universe” and “Self" are more general and

neutral terms than references to the Earth and to the Lord.

They do not preclude a traditional metaphysical and religious

understanding, but they also do not impose it. They thus avoid

an unnecessary narrowing down of the meaning of the two terms,

along with an equally unnecessary reification and a tendency

to religious effusiveness that all stand in the way of careful

philosophical analysis. Narrowness of interpretation, hasty

reification, and religious effusiveness: none of these three

prevalent tendencies in the Isha’s reception is warranted as

measured by the etymological root meanings we listed.

The historical reception of the Isha, though, has taken a different road. Exemplary

for it is Nikhilananda's (1949) translation, the second oldest

that I have consulted, which is remarkable for its attempt to

draw on Shankaras's commentary of the early 9th century CE,

one of the oldest testimony we have of the Isha’s history of

reception. Nikhilananda's translation is of particular interest,

as it makes the influence of Shankara clear by offering a

literal extract from relevant portions of Shankara’s commentary

and, based on it, brief explanations of all the key phrases

it uses:

All this

– whatever exists in this changing universe –

should

be covered by the Lord.

Protect the Self by renunciation.

Lust not after

any man's wealth.

(Isha,

1.1, as transl. by Nikhilananda, 1949, p. 201)

The explanations given are

these:

ALL THIS:

That is to say, the universe consisting of ever changing names

and forms, held together by the law of causation.

SHOULD BE

ETC: This universe, from the standpoint of Absolute Reality,

is nothing but the Lord. That it is perceived as a material

entity is due to ignorance. One should view the universe, through

the knowledge of non-duality, as Atman alone.

LORD: He

who is the Supreme Lord and the inmost Self of all. He is Brahman

and identical with Atman.

PROTECT:

That is to say, liberate the Self from the grief, delusion,

and other evil traits of samsara in which It has been entangled

on account of ignorance. To be attached to matter amounts to

killing the Self.

RENUNCIATION:

The scripture describes the discipline of renunciation of the

longing for offspring, wealth, and the heavenly worlds for him

alone who devotes himself entirely to contemplation of the Self

as the Lord. Such an aspirant has no further need of worldly

duties. It is renunciation that leads to the Knowledge of the

Self and protects Its immutability, eternity, and immortality.

LUST NOT

ETC: That is to say, a sannyasin [holy man who has vowed renunciation],

who has renounced all desires, should not be attached to what

he has or long for the property of someone else. Or the sentence

may mean that a sannyasisn should not covet wealth at all. For

where is the real wealth in the transitory world that he should

desire? The illuminated person renounces the illusory names

and forms because he regards the whole universe as Atman alone.

He does not long for what is unreal.

(Shankara's

comments on the Isha, as quoted in Nikhilananda, 1949, p. 201)

Shankara’s comments have been influential – and Nikhilananda’s translation may

have contributed to this influence – in that most of the subsequent

translations of which I am aware appear to follow Shankara's

understanding as conveyed by Nikhilananda's reading, with the

partial exception of the revised Müller/Navlakha translation.

Three examples must suffice:

All this is for habitation by the Lord, whatsoever is individual

universe

of

movement in the universal motion.

By that renounced though

shouldst enjoy;

lust

not after any man's possession.

(Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Aurobindo, 1996, pp. 19 and 29, PDF

version p. 5; my indents)

This whole world is to be dwelt in by the Lord

whatever

living being there is in the world.

So you should eat what

has been abandoned;

and

do not covet anyone’s wealth.

(Isha, 1.1., as transl. by Olivelle, 1996, p. 249)

The Lord is enshrined in the hearts of all.

The

Lord is supreme Reality.

Rejoice in him through renunciation.

Covet nothing.

All belongs to the Lord..

(Isha, 1.1., as transl. by Easwaran, 2007, p. 57, my indents)

Critical discussion: three key considerations

It is time to move on, from questions of translation

to a discussion of the Isha's message to a contemporary audience

of researchers and professionals, along with philosophically

interested lay people. I propose to focus on three main issues,

concerning (1) the legitimacy of a non-religious reading of

the Isha; (2) the meaning and value of a more philosophical

reading; and (3) an outline of the specific discourse-theoretical

interpretation that I propose and wherein I see its relevance

for reflective practice. All three discussions, especially the

first two, will be rather brief.

Short

discussion

(1): The religious bent of most translations The above translations, which may be said to be fairly representative

of the literature, share a strikingly

theistic bent and a tendency to establish religious demands

and restrictions. One must wonder to what extent such a reading is warranted by the relevant history of ideas

(which unfortunately is poorly documented) and to what extent

it must be called arbitrary, a possibility that can be seen

positive inasmuch as it leaves the door open for a more philosophical

reading.

It seems to me that a predominantly religious reading of the Isha Upanishad

may be called authentic in two main respects. The first characterizes

all Upanishads, the second is specific to the Isha and to a

very few other Upanishads. First, and basically, a religious

reading of the Upanishads may be called authentic inasmuch as

the Hindu tradition of thought has never distinguished as sharply

between philosophy and religion as does "Western"

thought. In the West, at latest since Kant's powerful critique

of metaphysics, we are accustomed to the idea that expressions

of religious faith and mystic experience have their legitimate

place in the human individual's search for meaning and orientation but not

in rational discourse and philosophical reasoning. Accordingly,

their proper place is seen in the private rather than public

domain of argumentation and decision-making. In

India's tradition of thought, today as in the past, there is

no such strict separation between religion and philosophy. Both

are equally involved in the quest for understanding the meaning

of life and its proper conduct, perhaps because such understanding is expected to translate

into corresponding religious and worldly practices, which

then together determine one's karma and prospect for

salvation from continuous rebirth (moksha). Given the

enormous importance of these ideas for the individual's fate,

the propensity for a religious reading of the Upanishads, especially but

not only in their popular reception, becomes understandable. However

one-sided one may find it, it is so deeply ingrained in India's

cultural heritage that it has become an indispensable part of

proper understanding. Still, such an understanding need not preclude a more philosophical

reading. We can acknowledge the authentic nature of the Isha's

religious reception without ignoring its further-reaching, philosophical

and indeed, emancipatory significance.

Second, and more specifically, while an exact dating of the Isha remains difficult,

its traditional Vedic writing style, along with the observation

that unlike most other Upanishads it is part of the Samhitas

(i.e., the early Mantra portion of the Vedas) rather than of

the later Aranyakas (see, e.g., Nikhilananda, 1949, p. 195),25) suggest

that its roots reach back far into the history of the Upanishads.

If this is so, we should not be surprised that its language

and imagery are those of the early Veda, even if its content points

beyond them. Alternatively, it might have received the written

form in which we know it today later in the history of the Upanishads

but its authors might none the less have chosen to attach it

to the Samhitas and to adopt a conforming writing style, as

the best way to reach its intended audience. In either case

it seems plausible to assume that it could hardly have dared

to hint at its epoch's subjugation of individual thought and

spirituality under the control of religious doctrine and brahmanic

authority, except in the rather concealed and indirect form

of traditional religious imagery. How else could it have encouraged

people to start freeing themselves from such subjugation and

to dare thinking (asking questions) rather than just

believing (practicing worship)? Thinking, that is, about those

fundamental metaphysical and existential-practical questions

that the Upanishads, to all our knowledge, were first to raise

in the history of mankind and for which the religious concepts

of brahman and atman – and likewise, I would argue,

the concept of jagat – were and remain important:

What are adequate ways to understand the universe (brahman)?

Who are we, or might have the potential to be, as human

individuals (atman)? How should we conceive of our place

in this overwhelming world of ours (jagat)?

To be sure, the Isha merely hints at these questions. For the reasons just considered,

it may not have been able at its time to articulate them more explicitly. The historical

development of Vedic consciousness and spirituality, which led

from the mantras of the Samhitas, via the doctrines and rules

of the Brahmanas and the meditations of the Aranyakas, to the

philosophical awakening of the Upanishads, did not happen overnight.

But it happened. The Isha stands at the turning point of this

awakening. It embodies an early expression of the Upanishadic

"rebellion" against the older focus on religious doctrines

and rules of which we have spoken. With this rebellion, the

rise of spiritual autonomy emerged as a new theme on

the Vedic agenda. Its sibling: the courage to ask philosophical

questions, and thus the rise of philosophical reflection.

We have, then, reasons to explore the Isha's philosophical significance along

with its popular religious reception. We can recognize the former without denying or "renouncing" the latter.

We can appreciate the Isha’s richness without taking sides.

Short discussion (2): Towards a philosophical reading Unlike

so many of its translators, the Isha's itself does not take sides.

Its Sanskrit wording

leaves room for interpretation. It eschews the religious effusiveness that characterizes a

majority of its interpreters and commentators. It speaks of "this"

and "that" world (an analytical distinction of two

basic types of references to the world, and of two conforming

modes of talking about it) in the neutral terms of a subject

(atman) that grapples with the tension between one's self-constructed,

individual universe (jagat), limited and unstable as

it inevitably is, and the larger, total universe that lies before

and beyond any individual grasp (brahman). Remarkably

it does so with no explicit use of the terms "atman"

and "brahman," as if to avoid their religious connotations.

Its references to atman and brahman remain implicit in the talk

of "this" and "that" world. By contrast,

it does use the term "jagat," a term that has no predominantly

religious connotations. So both its theme and its language remain

neutral and are as relevant to ordinary life practice and professional

practice (including research practice) as they are to religious

practice. What a philosophical exclamation mark!

The

wording of the Isha’s first verse is indeed like a philosophical

door opener. It opens the door for us and invites us to enter

and marvel at the philosophical depth of Upanishadic thought.

It lends itself to systematic thought about this world of ours

and ways to understand it, no less than to spiritual reflection

about that other world beyond it. Once again we can only admire such careful choice of language, in the Isha no

less than in the other Upanishadic texts that we considered when

we first encountered their language of "this"

and "that" – the Brihadaranyaka,

the Chandogya, and the Mundaka, along with the invocations to

all those Upanishads which are associated with the Yajur Veda (among them

notably the Brihadaranyaka, the Isha, and the Shvetashvatara

Upanishads).

What makes the Isha stand out is

its explicit use of the concept of jagat and, more specifically,

its reference,

in the first line, to jagatyam jagat, which literally

means "jagat [moving] in the jagats." Since the word

jagat as such already refers to a universe of moving phenomena

or, in Nikhilananda's (1949, p. 201) above-cited words, to

"this

changing universe … consisting of ever changing names

and forms,"

we have to understand the phrase "moving

in a universe of moving phenomena" as intended to bring in an additional, higher level

of cognition. This is the reflective level of a subject that realizes

(in the double sense of recognizing and bringing to life) its role

as the author of the jagat it is facing. As the author

of its jagat, this subject carefully selects and questions the context of phenomena

or circumstances that it takes to be relevant for dealing

with a specific situation or issue at hand, and within which

its thoughts and actions will consequently move. An element of choice

is involved since no conceivable notion of jagat is complete,

definitive, and objective beyond questioning. There are always

options for defining or redefining the universe

of thought and action within which an agent or speaker moves at a time. Or, as

we might now say: we always have a choice about the jagat within which we (are

to) move. Any such choice represents but one of an indefinite number of other conceivable jagats

for identifying aspects one considers to be relevant – aspects

of that larger, all-encompassing reality

that ideally could indeed count as a complete, definitive, and objective

universe of thought and action,

but which as such lies beyond human grasp.

In simpler but hardly

less thought-provoking terms: whatever

description of reality we rely on, it is bound to be false. False,

that is, to the extent we claim it to be a sufficient account

for deciding the question at issue. It is part of the human condition as we understand it today

that all our views of the world, all attempts to understand

it and to act properly in it, are very limited and fragmentary, inevitably

conditioned

by the particular universes (sic) of which we ourselves,

whether as individuals or as collectives, are the authors.

Only at first

glance is this notion of "particular universes"

an impossible one. At a closer look, it rather accurately captures the paradox we

face: in thinking and doing something about

an issue, we cannot help but to presuppose some universe of

thought and action within we move – a personal jagat

that will limit the scope of validity and application of our

conclusions but of which we nevertheless have to assume that

it is adequately universal so as to have us consider everything

that is relevant for judging the issue. However reasonably

we try to deal with the situation: reason

(i.e., reliance on shareable reasons) and reliance on particular assumptions (which others need not

share) do not go together easily. Accordingly, whatever universe we choose to move in, we

have to keep in view that it amounts to a particular selection rather than the total universe of all conceivably

relevant considerations and concerns; and hence, that we are

well advised to limit our claims accordingly.

It also

follows that accounts of what is "really"

the case tell us as much about

those who advance them as about the section of the real world

in question. What are the assumptions underlying the selection

of "facts" and "values" that this person

claims to be particularly relevant? Is she aware of these assumptions?

Is she prepared to accept that other assumptions may be just

as reasonable? Does she limit her claims accordingly? In short,

how does this person handle the inevitable particularity of

her views and validity claims?

The

basic implication of all this should be clear by now:

As soon as we assert that

some specific account represents a true and relevant description of reality, and/or amounts to correct and necessary proposals for changing

it, we almost inevitably claim more than what we can safely claim to know

or to get right. In discourse-theoretical terms, we should not

expect

that there is any method or form of discourse that could redeem

the claims people raise, even in methodologically disciplined

forms of theoretical or moral discourse. Accordingly difficult

it is for everyone to distinguish between adequately and not

so adequately justified claims, whether they are one's own claims

or those of others. This in turn makes claiming too much

a widespread tendency, a habit that often enough goes unnoticed

and unchallenged.

In Upanishadic terms, when

it comes to identifying and mastering the jagat(s) we

move in, we are for ever caught

in a quest for better knowing and understanding ourselves

– our inmost, individual Self, the author or creative principle (i.e.,

inexhaustable source of options) within us (atman) that shapes our perceived reality – just

as we are for ever on the way towards understanding the larger, ultimate universe

of which we are a part and which shapes all perceivable reality

– the creative principle and source of options beyond this world of ours that permeates

everything alive and conscious in this world (brahman).

Accordingly difficult – far from being trivial – it is also

for everyone to see and understand the jagats within

which other speakers and agents or entire groups of people move.

Short discussion (3): Towards a discourse-theoretical view The question that

interests me, but about which I have found close to nothing

in the literature, concerns the methodological significance

of the Isha’s reference to jagat. What does it mean for

our conceptions and methods of rational inquiry and practice?

The answer I have in mind is an indirect one: it might

change the ways in which we think and speak about the validity

claims

involved, for example, claims to knowledge, rationality, right

action, and resulting improvement. We may need to question some

of the usual ways we formulate such claims and justify their validity,

typically by referring to established methods of inquiry, reliance

on scientific conventions, consultation of individual expertise,

and division of tasks and responsibilities along organizational

and disciplinary boundaries. We might want to cultivate a

new kind of discourses about claims to relevant knowledge

and right action.

The basic idea in

support of this conclusion is simple: our notion of jagat, or what

we have thus far rather vaguely called the universe of thought and

action, is usefully understood in the terms of a universe

of discourse. The jagat we are to move in then becomes a question of the

specific universe(s) of discourse

that we consider relevant for identifying, assessing, justifying or questioning

the validity claims we raise or face in different situations

or contexts of action. To these claims belong basically all

suggestions about what the situation is and what ought

to be done about it, but also a number of related claims such

as who is or should have a say in answering these questions,

what notion of improvement should inform the analysis, and so

on.

There

is, however, a complication that we need to consider, lest we

oversimplify. It is that all these mentioned claims come up

not only at the object-level of reflection and discourse about

a situation of concern, that is, about what is "the problem"

and how it might be "solved," but also at the meta-level

of reflecting and discussing about how the relevant situation

should be delimited in the first place so as to be sufficiently

comprehensive, yet still manageable. The validity claims just

mentioned then amount to boundary judgments (Ulrich,

1983) as to what the universe of discourse is to include and

what it is to leave out. Discourse universes are thus defined

by a set of boundary judgments, the exact nature of which we

need not worry about at this place.

In

everyday language, we may think of our jagats – or now, universes

of discourse – simply as the sum-total of "that which we choose to talk about"

in formulating or discussing a problem; likewise, we might speak

of the "scope

of an argument" or the "system-in-focus" assumed

in a claim (D.P. Dash, 2013d) or simply of the contexts

of thought and action we care about. Obviously this contextual

choice embodies itself a claim, but it is a meta-level claim

that we cannot question at the same time at which we are discussing

the mentioned object-level claims as to what are the "facts"

(circumstances) and "values" (concerns) that are to

be considered relevant in dealing with a chosen "situation"

(context).

A

discourse-theoretical approach offers additional ways in which

one may conceive of such meta-level claims, whereby the emphasis

shifts from their descriptive or normative content (as in the

case of the boundary judgments at which I just hinted) to the

kind of discursive (and sometimes also non-discursive) obligations

they entail, that is, to the ways in which they can and need

to be redeemed. To this end I basically propose to rely

on the model of speech-act immanent obligations advanced by Habermas (1979, 1984; see my account

in Ulrich, 2009c,d).

In this model, we can distinguish a basic non-discursive or

pre-discursive claim – that an utterance be phonetically and

grammatically, perhaps also semantically, clear and understandable

– and three equally basic, genuinely discursive claims

– to the empirical truth and descriptive accuracy of what a

speaker says; to the normative rightness and legitimacy of its

value assumptions and implications; and to the authenticity

and sincerity of the speaker's intention. Habermas focuses on

the latter three validity claims, as in his view only they demand,

and allow of, discursive justification – the claims to truth, rightness, and

truthfulness. Implicit is the speaker's additional claim

that he is prepared to substantiate these claims

by advancing relevant evidence or reasons, if challenged to

do so, and thus to demonstrate what Habermas calls "rational

motivation," that is, the will to rely on no other force

than that of convincing arguments. Claims to truth accordingly

imply an obligation to

provide evidence of relevant facts; claims to rightness, an obligation

to justify underlying norms or principles of action; and claims

to truthfulness, an obligation to prove trustworthy. All three

claims need to be redeemed argumentatively, that is, by entering

into discourse and offering reasons for one's claims, as well

as by taking up and responding to the counterarguments of others;

truthfulness, in

addition, calls for consistency of the speaker's previous and

subsequent

behavior.26)

So

much for a basic outline of a discourse-theoretical perspective.

This is not the place to provide a more detailed introduction

to Habermas' discourse theory or, more specifically, to the Toulmin-Habermas

model of rational discourse that I have adopted as argumentation-

and discourse-theoretical framework for my work; suffice it

to refer the reader to my detailed earlier accounts (see Ulrich,

2009c, d; 2010a, b; and 2013a). Instead, I would like to suggest

four more specific, though still fairly elementary observations

as to how the proposed discourse-theoretical perspective might

enhance our understanding of the Upanishadic concept of jagat;

and conversely, how a philosophical rather than religious reading

of the Upanishads could enhance our understanding of the discourse-theoretical

approach.

First

observation: Just

as a discourse-theoretical interpretation can shed new light

on the Upanishadic concept of jagat, the latter can help

us better understand the implications of a discourse-theoretical

concept of rationality. We have here two different but complementary

accounts of what it takes to gain valid knowledge of reality:

the Upanishadic account tells us that in the first place we

need to get our jagats right, whereas discourse theory

lets us understand how we can think and speak rationally

about them, namely, by uncovering and substantiating the specific

validity claims involved.

Habermas

explains the difficulties involved as a problem of achieving

rationally secured (or "rationally motivated")

consensus, which in today's pluralistic world is obviously

a scarce resource. As my regular readers know, I do not follow

Habermas in this respect. I prefer to base my account of (and

hopes for) rational discursive practice on a discourse theory

of critique rather than a discourse theory of consensus

(see, e.g., Ulrich, 2003, p. 326). The Upanishadic account

is superior in this respect, as it does not risk passing over

the essential methodological difficulty, namely, that all our

universes of discourse are self-constructed and therefore also

changeable and open to challenge, however "rational"

we are. We should never take them to be more than preliminary

agreements or conventions. It would seem, therefore, that no

amount of discourse and no kind of rationally motivated consensus

can overcome this limit to human knowledge and rationality.

This

is where a second limitation of Habermas' model of rational

discourse becomes important to me: it does not offer

a systematic account of the ways in which our jagats or universes

of discourse are informed by contextual boundary judgments,

so that we could examine them in a methodologically clear and

disciplined manner. To this end, my work on critical systems

heuristics (CSH) proposes a typology of boundary categories

and questions, along with a model of cogent critical discourse

to which I refer as boundary critique or boundary discourse.

Like in the case of Habermas' work, this is not the place to

introduce the CSH framework of boundary discourse in any detail

(see, e.g., Ulrich, e.g., 1983, 1987, 1993, 2000; Ulrich and

Reynolds, 2010); suffice it to mention that I see in it a discourse-theoretical

response to the Upanishadic challenge of the jagatyam jagat,

the notion that all our knowledge and reasoning moves within

moving (i.e., unstable) jagats (real-world contexts).

Second

observation: In a combined Upanishadic-discursive

perspective, rational practice and rational discourse become

inseparable in a deeper sense than is usually asserted. How

we act is always an expression of how we think, and how we think

has a lot to do with the universe (jagat) within we move. It

is to be expected that the empirical circumstances and normative

concerns we see as relevant "facts" and "values"

will differ with the assumed universes of discourse. People's

validity claims conflict with those of others not just

because the ones get their facts and value judgments right and

the others don't but rather, because the parties move in different

universes and thus risk talking past each other.

Rationally

arguable practice thus becomes a fundamentally discursive

quality of how we deal with divergent discourse universes

and with the conflicting validity claims they entail. The etymological

root meaning of "discursive" is quite relevant here:

the Latin verb discurrere means as much as to "run

off in different directions," "diverge," or "run

back and forth." Such a focus contrasts with the conventional

understanding of applied science, professional competence, and

expertise (henceforth just "expertise"), where reference

to (supposedly) superior knowledge and competence is usually

taken to be sufficient for justifying claims, at least with

respect to relevant facts (but in effect often also to relevant

value judgments, as factual and normative judgments are not

independent). Nor does this conventional understanding recognize

that when it comes to boundary judgments, experts have no natural

advantage of competence over lay people but depend on the discursive

engagement of concerned citizens (see, e.g., Ulrich, 1983, 1993,

and 2000 for detailed and illustrated theoretical accounts).

An Upanishadic concept of discourse thus takes on a methodologically

more fundamental and further-reaching role than in the currently

prevailing concept of expertise. It is more fundamental

in that in addition to object-level discourse on the issues

or situations of interest, it brings into focus the role of

considered universes of discourses and suggests a discursive

approach to unfolding related contextual assumptions and implications.

It is further reaching in that it extends the concept

of expertise discursively so as to give concerned citizens a

meaningful role to play. These two extensions of the currently

dominating model of discourse move at different conceptual levels

inasmuch as the first requires a meta-level discourse and the

second, an object-level discourse; what they have in common

is that boundary discourse will be a crucial tool for driving

critical reflection and debate at both levels.

A

thus-extended, discursive concept of expertise coincides remarkably

with an Upanishadic view of inquiry. The Upanishadic ideal of

an inquiring and self-reflecting mind cannot content

itself to move within a given jagat; rather, it will

always aim for that higher level of consciousness (or

now, of discourse) which it associates with the search for brahman,

and at which alone right thought and conduct can be achieved.

We are reminded here of the Vedic distinction introduced earlier,

according to which knowledge is twofold: para

(lit. = higher, i.e., postulational or suppositional, second-order)

and apara (lit. = lower, i.e., observational or practical,

first-order). In such a perspective, boundary discourse represents

a higher level of discourse aimed at para vidya, whereas

ordinary discourse about factual and normative claims moves

at the lower level of apara vidya (compare Ulrich, 2015a,

pp. 6 and 8f).

Third

observation: Continuing the line of argumentation

of the previous observation, a combined Upanishadic-discursive

perspective not only leads us to recognize that our discourses,

as rational as they may be in the terms of the Toulmin-Habermas

model of discourse, are conditioned by the jagat(s) within we

move; it also suggests that the jagats at work can and should

themselves be subjects of discourse (the mentioned "higher"

or meta-level). We have here a core consideration of what we

might indeed call an Upanishadic concept of discursive rationality,

and consequently also of discursive expertise. In addition

to the Toulmin-Habermas logic of discourse, it takes up the

Isha's point, according to which we have to conceive of all

human knowledge and thought in terms of jagatyam jagat,

"jagat moving in the jagats."

The

essential methodological consequence consists in the importance

of securing reflective and discursive chances for unfolding

contextual boundary assumptions, so that conflicting views and

claims can be seen in their light. How do relevant facts and

values change when the considered universe of discourse changes?

And conversely, may we need to adapt our universe of discourse

in the light of new facts or value considerations that have

come up in the discourse? What options are there to see relevant

contexts, so that previously divergent judgments of fact and

value might become partly shareable or at least the parties'

differences become mutually understandable, according to the

motto "we can agree that (and why) we don't agree"?

Such questioning can open up chances for learning and cooperation.

It can promote a new sense of appreciation and tolerance for

the value and validity of conflicting claims and perspectives.

Rationally motivated discourse and contextual self-reflection

can thus mutually support one another.

The

important point is that implementing such an Upanishadic concept

of rationality and expertise requires its own form of "higher"

discourse,

to which I have referred above as boundary discourse. The

basic underlying idea is the critical turn of our concepts

of rationality and expertise, which means that discourse and

expertise are properly understood as means for questioning,

rather than justifying, validity claims. In the face of divergent

universes of discourse, claims to sufficient justification

are relatively (sic) meaningless, but sufficient critique

in the form of surfacing the influence of diverging contextual

assumptions is not. This idea corresponds to the stance of humility

and tolerance which we have encountered in the Upanishads, for

example, in the Mundaka's admonishment that inquiry should be a practice "free from self-will" (Mundaka, 3.1.6, as transl.

by Easwaran, 2007, p. 193, quoted in more detail in Part 4,

Ulrich, 2015a, p. 10). We also recognize this same

stance in the Isha's call for "renouncing." The point,

to be sure, is not that we should throw the ideal of sufficient justification over

board but only, that we should understand it precisely as such:

as an ideal that embodies a critical

standard or principle only, a demand for systematic efforts of uncovering the unavoidable

lack of complete justification in all our claims. The

quality of discourse is then to be understood in terms of a

new ethos of justification:

The

rationality of applied inquiry and design is to be measured

not by the (impossible) avoidance of justification deficits

but by the degree to which it deals with such deficits in a

transparent, self-critical, and self-limiting way. (Ulrich,

1993, p. 587)

Fourth

observation: With the spotlight it throws on

contextual choices, an Upanishadic concept of expertise leaves

us with no illusion about the conditioned nature of even the

most thoroughly argued claims to knowledge and rationality.

Except perhaps in the case of purely analytic (deductive) reasoning,

with which we are not concerned here, they all depend to some

extent on suppositional reasoning. Suppositional reasoning

involves the drawing of conclusions from assumptions rather

than from complete evidence; in this case, assumptions concerning

the jagat(s) we take to represent the proper universe(s) of

discourse. But of course, once we recognize this role of suppositional

reasoning, the charge of a bottomless relativism is bound

to come up sooner or later.

There

is not much we can say from an Upanishadic perspective to counter

this charge, I fear; for no human quest for knowledge and rationality

can entirely escape the need for suppositional reasoning (insofar

the charge may be said to be a trivial, if not somewhat cheap

accusation). This is of course precisely why the Vedic sages

found it necessary for human thought to work with a counterconcept

to jagat such as brahman in the first place – the notion

of an all-encompassing, absolute universe of thought that would

be self-contained and thus independent of anything not included

in or controlled by it, not unlike Kant's (1787, B364, 367,

379f, 382f, 444, 445n) notion of a totality of conditions that

would itself be unconditioned (as discussed in Part 2 of this

series, Ulrich, 2014a, see esp. pp. 2f and 6-8).

With

a view to our present interest in a discursive understanding

of the Isha's reference to jagat, I suspect my main line

of argumentation would be that yes, relativism is part of the

human condition. It is inevitable in all human practice (including

discursive practice) and that is precisely why it matters that

we strive for that higher level of consciousness that Upanishadic

discourse embodies, understood as the search for brahman

or, as we might now say in the light of the preceding conjectures,

as a confluence of Upanishadic reflection and discursive critique

of validity claims in terms of underlying boundary judgments. To be

sure, that higher level of awareness and argumentation will

still not free us altogether from relativism; but at last, it

will make us aware of the sources of error and mutual misunderstanding

involved and thus can help us avoid or minimize them.

It

is, then, fair to say, I think, that I am

not singing the gospel of relativism here. Quite the contrary,

I am concerned with ways to handle it properly.

Precisely because we cannot avoid relativism, we need

to handle it in critically self-reflective and discursive

ways such as Upanishadic discourse supported by systematic processes

of boundary critique offers them. The underlying rationale is

that the trap we need to avoid is not relativism as such but only

a

relativism that remains unreflected and undisclosed with regard

to how it conditions our claims.

Only to that extent – we might

say, inasmuch as we are not aware of a speaker's or agent's actually "considered world"

– the claims concerned risk becoming sources of error

and lack of mutual understanding.

Some

conclusions: Towards Upanishadic discourse

We have reached a point where the Upanishads are

beginning to enhance, perhaps even to change, not only our understanding

of the role of general ideas in human thought and action but

also, linked to it, our understanding of "rational"

discourse. A new notion of "Upanishadic" discourse

is emerging. Before we complete our discussion of the Isha's

message, let us briefly pause and, at the risk of repeating

things we have already understood, briefly sum up some of the

basic lessons that we have learned thus far, so as to realize

where we stand.

Basic

Upanishadic notions, discourse-theoretically understood

Perhaps most basically, the Upanishadic language

of "this" and "that," together with the

related distinction of "lower" (first-order) and "higher"

(second-order) knowledge, have helped us understand

that whatever particular

universe of discourse we move in, we should not confuse it with that other universe

"without a second" which alone would represent

a true and sufficient universe of discourse and which consequently

would be basically the same for everyone ("one only"). This

would be a universe of discourse that in principle everyone

would be able to share, although in practice no-one of this world

(no discourse participant) can ever credibly claim to know

and master it entirely. And yet, to the extent we aim to achieve

genuine mutual understanding, we must find ways to share our

individual worlds, lest we end up talking past one another.

In

the world of the "this" rather than the "that,"

it is clear that there will always be options for defining some

shareable universe of discourse. Accordingly some basic, shareable

standards and procedures for achieving mutual understanding

on such options will also be needed. The general ideas

we have been considering in the different parts of this series,

along with the related series of Reflections on Reflective Practice,

embody such standards: the systems idea, the moral idea,

and the idea of discursive rationality. We have characterized

them, inter alia, as the indispensable quest for (or

criterion of) comprehensiveness; as the principle (or criterion)

of moral universalization; and as the demand for (or criterion

of) rational motivation, respectively. The Upanishadic ideas

of atman, jagat, and brahman have made us see

these standards in a complementary perspective. As we begin

to appreciate, they point to a need for searching even deeper,

by reflecting on the role of suppositional reasoning and of

our inmost sources of subjectivity, of selectivity, and of aspiration

in it.

We

might, then, understand these three core ideas of Upanishadic

thought as embodying three different, but not independent, frames

of reference for defining and reflecting upon one's universes of discourse, whereby:

- atman

would refer to a speaker's private, often at

least partly unrevealed

and partly also unconscious, universe of discourse, one

that is

rooted in one's innermost feelings and thoughts, values

and wishes with respect to the situation or issue in

question, as well as in one's personal biography and conforming

sense of identity;

- jagat

would refer to a speaker's considered universe

of discourse, the real-world context one considers relevant

for assessing a situation or issue of concern and which

is never "given" in any definitive way

but always again needs to be identified by judgments that remain

open to question and challenge; and finally,

- brahman

would refer to the ideal notion of a total universe

of discourse, an all-encompassing notion of the context

in question that no individual speaker can ever hope

or claim to master but which theoretically would include everything

potentially relevant for, and everybody potentially concerned

by, the issue or situation at hand, so that it could

serve as a universally shareable and in this sense "objective"

basis for agreeing on claims to proper knowledge and action.

From

a discourse-theoretical view of the Upanishads to an Upanishadic

view of discourse One might object that such a

discourse-theoretical use of Upanishadic core ideas amounts

to an instrumentalization, or at least to a one-sided perspective,

in that it merely asks how useful or relevant Upanishadic core

ideas look from a discourse-theoretical perspective, with a

view to employing them for a basically "Western" approach.

Indeed, one may with equal right reverse the perspective and ask

how Western ideas look in the light of an Upanishadic framework.

A basic example

might be the conventional Western opposition of theory and practice

or, within a discourse-theoretical framework, the distinction

between theoretical and practical discourse. In

Upanishadic terms we might speak of the path of knowledge (cultivating

careful contemplation and reflection) as distinguished from

the path of action

(cultivating good practice and change). Unlike the Western theory-practice

dichotomy,

which often is (mis-) taken to imply that theory and practice are fundamentally different

categories and therefore allow of separate treatment, the Upanishadic

view emphasizes that both are legitimate paths of learning.

The quest for practical excellence is worth no less than the

search for theoretical mastery. To be sure, it is often advisable

to concentrate on one of the two paths of learning, so as to

achieve proper results and get far enough on the chosen path.

Accordingly the man of knowledge is often expected in Upanishadic

texts (including the Isha) to "renounce" the path

of action and worldly endeavors just as the man of action is

expected to focus on practice. Even so, it is quite clear that

both paths represent

legitimate and effective paths of learning, if chosen in accordance

with one's talents and circumstances of life. Likewise, both

paths involve learning and practicing with a teacher

or a person of superior achievement, through interaction that

is based on careful listening, observation, and dialogue. The discursive

element, then, is not a newcomer, much less a stranger, to Upanishadic

thought. Rather, I think it is fair to say that it is deeply intrinsic

to the Upanishadic conceptions of proper knowledge and proper action.

Both require learning; but learning is always a fundamentally

discursive endeavor, for it involves moving consciously and

carefully within and across one's considered (or accustomed)

jagat.

This insight in

turn makes it understandable why for an Upanishadic thinker,

both the path of knowledge

and the path of action amount to a continuous search

for clarifying and developing one's conceptions of atman,

jagat, and brahman – a quest for coming to terms with fundamentally

divergent universes of discourse, that is. They are fundamentally

divergent – rather than just different – in that they represent

discursive universes of different nature or type; yet the pursuit

of excellence has no choice but to try and reconcile them in

thought and action, even if it will never succeed completely

in this endeavor.

The

earlier-introduced notion of a "double movement of thought"

is relevant here; we may understand it to be part of all learning,

which also means it is part of both the path of knowledge and

the path of action. (We might also speak of a double reflective

or discursive movement rather than a movement of "thought,"

lest we fall into the trap of associating it with the path of

knowledge only but not also with that of action, of which thought

is an inherent element as well.) In systems-theoretical language,

we might describe the basic reflective movement that Upanishadic

thought calls for – the search for brahman – as an expansive movement;

in Kantian language, as an enlarging movement of thought

and engagement. It

begins with one's "private" perceptions and concerns

and then works towards an increasingly richer and objective notion

of the issue or situation at hand. But, as the Upanishadic perspective further

suggests, that is not the end

of it. Learning never boils down to a unidirectional search

for brahman

(systems expansion striving for comprehensiveness). The aim of this expansive

movement of reflection and discourse – the quest for knowing and becoming one with brahman

– is obviously an ideal. Both an Upanishadic and a discursive

perspective (the latter in the full sense of the Latin discurrere)

suggest to me that a reverse,

critical movement is of equal importance, one that moves

from supposedly comprehensive notions of situations or issues towards the innermost, unrevealed sources of perception

and engagement (or in the terms of critical systems heuristics,

the sources of selectivity and motivation) that are at work

in all human thought and action – the Upanishadic quest for knowing, and

becoming one with, one's atman. Thus combined, these

two "Upanishadic" movements of thought not only show

a deeply discursive orientation, they indeed yield a basic heuristic

for operationalizing the basic aim

that has emerged from this series of essays (at latest in Part

3), the search for a practicable framework

of critical contextualism.27)

So

much for a brief summary of where we stand. Back now to the

Isha's first verse, the text around which we have organized

our discussion in this present third essay on the Upanishads.

Continuing in the vein of the previous reflections, I propose

to conclude this discussion in a somewhat personal way. I will

first articulate my individual reading experience with the Isha's

first verse, and will then try to sum up this experience in

a free and unconventional rendering of the verse in English. In this way

I hope to help readers appreciate the Isha's message to the

contemporary researcher and professional as it results from

our exploration thus far – a message that is informed through

a discourse-theoretical reading but still tries to remain faithful

to the spirit and basic ideas of Upanishadic thought.

Some final thoughts on the Isha and my experience of reading it

Through an idea history that unfortunately is poorly documented,

the Isha's Upanishadic core theme of striking a balance between

"this" and "that" world, so as to allow

them to "become one" in our minds as a source of right thought

and action, has historically been turned

into a call for renunciation that was misunderstood as

intending deprivation rather than reconciliation.

As far as I can see and judge from countless hours of working

with Sanskrit dictionaries and studying different translations

of the Isha, along with learned commentaries on the Upanishads,

an adequate modern (i.e., secular) translation and discussion

of these sources of ancient wisdom is sadly missing today. It

seems to me that the presently available, religiously oriented

translations and commentaries obscure the Isha's message and relevance to

us today, rather than clarifying it and making it widely accessible.

Specifically regarding the Isha's first verse, my impression is that neither

its specific wording nor the larger Upanishadic context to which

it belongs require a narrowly religious reading as I have

encountered it throughout, with relatively minor variations.

Even Müller and Navlakha (2000) do not entirely avoid the

trap in their revised translation of the Isha's first verse

(as quoted at the outset above). Still, theirs remains the most

neutral translation in this regard. For the reader's convience,

I here reproduce the selection of translations that we have

considered earlier in this essay:

All this is for habitation by the Lord, whatsoever is

individual universe

of movement in the universal motion.

By that

renounced though shouldst enjoy;

lust not after any man's

possession.

Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Aurobindo, 1996, pp. 19 and

29, PDF version p. 5; my indents) This whole world is to be dwelt in by the

Lord

whatever living being there is in the world.

So you should

eat what has been abandoned;

and do not covet anyone’s

wealth.

Isha, 1.1., as transl. by Olivelle, 1996,

p. 249) The Lord is enshrined in the hearts of

all.

The Lord is supreme Reality.

Rejoice in him through

renunciation.

Covet nothing. All belongs to the Lord..

Isha, 1.1., as transl. by Easwaran, 2007, p. 57, my

indents) All

this – whatever exists in this changing universe –

should be covered

by the Lord.

Protect the Self by renunciation.

Lust not after any

man's wealth.

(Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Nikhilananda, 1949,

p. 201) All

this, whatsoever that moves on earth

is to be hidden in the Lord

(Self).

When thou hast surrendered all this,

then thou mayest

enjoy.

Do not covet the wealth of any man.

(Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Müller, 1879, p. 311; line-breaks and

indents added)

All this, whatsoever that moves in this

moving universe

is encompassed by the Self.

When thou hast

surrendered all that [i.e., the material wealth],

and wilt seek not

what others [continue to] possess,

then thou mayest truly

enjoy.

(Isha, 1.1, as transl. by Müller and Navlakha, 2000, p. 17;

my indents; read "that" as "this")

All translations agree

that the key phrase jagatyam jagat is to be read as a

predicate of idam sarvam (this entire world of

ours). All translations except Easwaran's then also offer a

rather neutral and accurate translation of this key phrase as

conveying the idea of something "moving

in this moving universe." However, only Müller and Navlakha subsequently

avoid a one-sidedly theist rendering of the further predicate

isha vasyam as referring to a supreme, almost biblical

God ("the Lord") who is assumed to be inhabiting (or

dwelling in, vasyam) the whole world. The less narrow

root meanings of isha as a source of authorship, ownership,

and mastery in the widest sense of these terms (ranging from

control of a piece of land to mastery of a subject and to self-control),

are lost. Müller and Navlakha's alternative

translation by means of the formula "is encompassed by

the Self" is not particularly clear and helpful either, and

it is certainly not the most adequate translation

one could

imagine from a discourse-theoretical perspective; but at least it leaves the door

open for a secular and philosophical reading. The Isha's first line, isha vasyam idam sarvam, yatkincha jagatyam jagat,

then yields a truly fundamental epistemological reflection that

we might formulate in the following way (or similarly):

This entire

world of ours, whatever it includes (or what we take it to be),

is always shaped

by its author, the Self. (Isha 1.1, my approximate transl. of

the first line)

Only

a consistently secular reading along such lines reveals this

timeless relevance of the Isha. Whether and to what

extent the author-Self to which it refers is to be identified with atman or with brahman

or even with a personified God, or else simply with a human

speaker or agent, remains in such a reading left to the interpreter

and can be

decided depending on the context, and this is good so.

One

might object that my reading is obviously biased by an epistemological

rather than theological interest, and I would not deny that.

Even so, in view of the etymological root meaning of isha as "possessing

strength" or "mastering" and "owning"

something, or being a "master, speaker, author," and

so on – meanings that still come to the fore in the word's contemporary

use; compare, for instance, the Spoken Sanskrit Dictionary, entry

"isha"

– it is difficult to see why such a translation should be called

arbitrary. Its wording lends itself to both a secular or a religious reading

and

insofar is certainly not arbitrary. Quite the contrary, it seems

to me less arbitrary and rather more accurate than

any predefined reference to a personal God along the lines of the

Judeo-Christian tradition ("the Lord"), a reference

one might just as well suspect to have been imposed on the Sanskrit texts

by their early,

Western translators rather than amounting to a compelling translation.

Be

that as it may, more important to me is that the overall

result of the suggested secular, open-minded approach makes perfect sense

and is apt to relate the Isha's message to our present epoch.

The Isha's message can then be understood to admonish us of

the omnipresent, because all too human, lack of thought and

awareness that characterizes our epoch no less than any previous

epoch of humanity:

All we may perceive

to make up this world of ours, and all we can say about it,

amounts to the expression of an unstable

and fragmentary universe of discourse (or jagat) that

we construct for ourselves, but which we should never confuse

with that other reality behind and beyond it that would amount

to the proper universe of discourse. (Isha 1.1, personal, discourse-theoretical

reading of the entire verse)

From a discourse-theoretical

perspective, such a translation hits the nail on its head, I

think. Moreover, unlike its religiously oriented siblings, it

may be said to be undogmatic in that

it leaves the door open for a more religious or spiritual reading to

those who prefer.

So far, so good. Let us now turn to the second line of the Isha's first verse.

Up to this point I feel that Müller and Navlakha's revised translation

is clearly the most openly worded and accurate, and thus supports

the above reading adequately, especially if one considers that Müller

did not have available at his time the option of

a discourse-theoretical understanding. But then, Müller and Navlakha go on and (I

cannot say it otherwise) mistranslate the

next crucial term of this first verse, tyaktena (a

composite term consisting of the etymological root terms tyakt

= "to derelict, abandon, leave" and ena = "[a

course, way] to be obtained") as a mere call to "surrender all

this

[material wealth]" (the brackets are theirs). While they are careful enough to point

out, by using brackets, that the reference to "material

wealth" is added by them rather than being original, they

apparently found no better English term than "surrender"

for expressing the Isha's demand for self-restraint and, as

we formulated it above, for not

claiming too much, tyaktena.

Similarly, Nikhilananda's

and Aurobindo's earlier-cited translations call for "renouncement"

and Olivelle's for "abandonment" of others' "wealth"

or "possessions." Such translations indeed

obscure the Isha's profound and multi-faceted wisdom, instead

of formulating it in a way that would provide room and impetus

for different strands of thought, as well as for relating it

to the pursuit of rationality, competence, and excellence in

multiple domains of our present world. The Isha thus appears to boil down (or

at least risks being misunderstood thus) to a mere call for

religious devotion and yes, for "surrender," rather

than for autonomous (i.e., responsible) and critical (i.e.,

self-reflecting) thought and action – the very contrary of spiritual

autonomy and enlightenment as the Upanishads seek to encourage

it. Genuine thinking

never surrenders to any demands other than those of self-reflecting

and responsible thought and action. Nor must it ever surrender to any

external authority, not even a brahmanic authority. It has no

choice but insisting on its autonomy, which includes its right

to rebel and say "no," perhaps even to provoke rather

than to surrender – an insight that earlier we found to stand at the beginning

of the Upanishads' history of ideas.

Looking back and reflecting on my reading experience with the Upanishadic

texts, I cannot help thinking of Martin Heidegger's thought-provoking

account of what thinking has the potential to be:

Thinking is thinking when it answers to what is most thought-provoking.

In our thought-provoking time, what is most thought-provoking

shows itself in the fact that we are still not thinking. (Heidegger,

1968, p. 28).

It may be time for a new reception of that ancient first verse of the Isha,

one that would be more thought-provoking and thereby also more faithful

to the spirit of the Upanishads. Such a translation would need

to leave room for multiple, richer and less one-sided readings

and translations than those prevailing today. And for interpretations

that would surely also be more immediately relevant to our contemporary

human condition, and thereby more accessible to contemporary

readers. All this and more stands to be gained; it should be

done.

To be sure, it should be clear that my sketch of a discourse-theoretical reading hints at just one of

many conceivable options to be pursued by a renewed contemporary reception

of the Upanishads.

I am thinking, for example, of the huge diversity of contemporary philosophical

strands that might serve as sources of interpretation and discussion.

Discourse theory is merely one of them, one that I find useful

for a contemporary approach to quite a number of thought traditions,

among them practical philosophy, American pragmatism, and (critical)

systems theory – three strands of thinking that inform my work

on critical systems heuristics but which many of my readers

may want to replace by other strands of importance to them.28)

Further, it might be stimulating to analyze the Upanishads

in the light of different practical and cultural or institutional

contexts, ranging from professional to organizational, managerial

and political contexts in different cultural environments, all of which might benefit from engaging

in "Upanishadic discourse."

The potential for a more contemporary reception looks huge indeed. If I have

not been able to do more than hinting at it, it is that

I am all too well aware of the limitations of my preparation

for the job. They make it clear to me that I need to leave such

work to the specialists, in particular, to linguists and discourse

theorists steeped in Sanskrit, together with scholars of Indian

history and philosophy and of Upanishadic

thought in particular. Or is such self-restraint perhaps entirely mistaken, not

only because it may run against the inquiring and rebellious

spirit of the Upanishads but perhaps also because the Upanishads are too important to be left to the specialists?

Or conversely, are possibly even the few conjectures that I

have been able to offer already too much and imprudent, in that

the only way to be faithful to the Upanishadic spirit (and in

any case to be on the safe side) would have been to remain silent,

if not withdrawing to the forest? (But that would represent

a Vedic – and Buddhist – rather than Upanishadic spirit, I suppose.)

As a final reflection, I suspect that as an author coming from the worlds of Kant and of contemporary

practical philosophy, along with social science and systems

methodology, and having moreover only just begun to discover

and explore a new and bewildering land of thought, I may have

tended to be somewhat quick and effusive in writing home about

my first impressions. Perhaps I am moving on firmer

ground, however, when I express my belief that from a Western

perspective, it is truly regrettable that the contemporary,

secular relevance of Upanishadic thought (or at least its potential

for having such relevance) has remained and risks remaining

largely unrecognized and underestimated in the West, due to

a reception that seems to presuppose that years

of religious devotion, meditation, and renouncement of secular

concerns are a condition for adequate understanding. To speak