|

|

|

Helping

researchers reflect and write about their practice We

tend to think of research as a systematic form of

inquiry that is regulated by conceptual frameworks, theories,

and methods, and the aim of which is to establish new knowledge.

This is not wrong, but it is seriously incomplete. Research

is also, and first of all, a kind of social practice. What forms

of inquiry are considered "research"; how we do it and how

we assess and use its results; the ways it shapes our perceptions of reality

and our notions of knowledge and expertise – these essential

aspects of our understanding of research are all

socially constructed (see Berger and Luckmann, 1966); that is,

they evolve through practice.

Moving

from the general notion of "research" to the level

of specific research efforts, a similar observation applies.

The aims and requirements that researchers associate with a

specific research effort, no less than the assumptions

that inform its findings and conclusions, will be shaped as much by the specific research

context at hand as by general epistemological, methodological

and sociological notions research; for it is only the specific

context that allows defining what is needed and relevant.

Research quality, then,

is no less a matter of research practice than

it is a matter of what for lack of a better term I will call

"research theory." Research theory as I understand

it is made up not only by general theories of knowledge and

science (an influential example is Popper, 1961, 1963, and 1972)

but includes all kinds of theoretical and methodological frameworks

and

other social conventions –

for social conventions they all are – that stipulate what

researchers are expected to do and what accordingly in

the worldwide research community as well as in the public domain

is to be considered respectable research. By research practice,

on the other hand, I mean what researchers actually do when

they "research" a specific issue or situation

and try to do justice to it, so as to come up with valid and

relevant findings and conclusions. This effort requires reflection

on how theoretical and methodological concepts can usefully

be put into practice and adapted to the situation; it also requires

a proper handling of all those genuinely practical

aspects of research that are indispensable to do justice to

the situation but which cannot be derived from general research

theory and justified in its terms, for example, because they

depend on the specific views and interests of the people involved

or in some way concerned.

To

be sure, as a matter of principle it is hardly adequate to oppose

research practice to research theory; adequate research theory

and practice should mutually inform one another. Adequate research

theory would thus be grounded in and support research practice,

and vice-versa. Unfortunately, this is not exactly the current

state of the matter. Practicing researchers are often lost when

they turn to the theoretical literature for advice about research

practice. The bulk of established research theory has focused

so much on the abstract, cognitive and methodological requirements

of research that it has tended to lose sight of the importance

of those other, "practical" aspects of research that

cannot adequately be described and decided in terms of research

theory, or at least not only so. For example, an

important aspect of what I mean by research practice is its

"self-reflective" quality: do the researchers

involved in a specific inquiry systematically question the manifold

assumptions on which its results depend and do they lay them

open, as well as making sure that all the users understand their implications for all

the parties concerned?

Another, related aspect of research practice is its "emancipatory"

quality: does research tend to make those it is supposed to

serve depend on its ways to define and answer the issues in

question, so that in effect

it puts them in a situation of incompetence, or does it enable

them to play a competent role?

My

philosophical as well as "applied" interest in such research-practical

questions explains why I have become

a co-editor of the Journal of Research Practice (JRP),

a journal that aims to help researchers in sharing

and improving their research practices.

Since

its inception in 2005, the journal has managed to maintain quite

a

remarkable level of quality; but this has gone at the expense

of rejecting many submissions or requesting revisions that did

not ultimately result in publications. As a consequence,

there has been a certain lack of papers that the journal was

able to publish on a regular basis without compromising its

standards of quality. There was thus a very practical need for

helping potential authors – researcher practitioners and scholars – in preparing

submissions that respond to the journal's aims and quality standards.

The

JRP Concept Hierarchy To do something

about the situation I initiated, together with my co-editor

D.P. Dash, the development of a specific

kind of research dictionary or

"taxonomy" for the journal. A

taxonomy is a systematic, hierarchical classification of concepts

that are considered useful for describing essential objects

or topics in a certain field of interest. A well-known example

is provided by biological taxonomies of species, say,

a taxonomy of plants (or of a subcategory of plants, say, flowers).

Such a taxonomy allows identifying individual plants (or flowers)

systematically on the basis of certain observable characteristics.

These characteristics then permit a step-by-step procedure of

examining and specifying the precise kind of plant one faces,

as if in a decision tree.

To

be sure, a research taxonomy is a more complex undertaking;

the aspects of research that can be of interest to research

practice are so multifaceted and interdependent that they can

hardly be arranged in the form of a strict decision tree. A

better way to approach the task is by thinking of these aspects

as elements in a complex conceptual network that we want to help

users explore, beginning at any place and moving in all

directions. The more important it is that the concepts in questions

are arranged and defined hierarchically, so as to provide a

basic structure of order in the form of higher-level and lower-level

concepts.

In

cooperation with my fellow editor D.P. Dash, we designed

the basic structure and initial content of what we call the

JPR Concept Hierarchy. It has a three-level

structure, and its initial content consists of well over 5,000

entries (but it is clear that many more entries will need to

be added as the intended users make the framework their own

and suggest new entries to meet their needs and interests).

It aims to be a tool that researchers can use to reflect on

their research and write about how they understand, practice,

and experience it. At the same time, it aims to be a tool for

the journal's editors in defining and communicating JRP's thematic

priorities and editorial focus, so as to strengthen its profile.

Ultimately, all the journal's readers, contributors, and staff

belong to the intended users: readers can use it to find

in the journal material of interest to them; authors and commentators

can use it to make sure their contributions respond to the interests

of the journal, as well as to index their content; and the editorial

staff and reviewers can use it to support well-founded decisions

about individual submissions, by considering whether a paper

contributes to the journal's aims and how it can be made to

focus more clearly on one of its thematic priorities, as well

as how it may be properly classified and indexed.

The

term "concept hierarchy" may require some further

explanation. Basically, a concept hierarchy is exactly what

the term says – a conceptual framework that is structured hierarchically

and is to form the nucleus of a specialized language (terminology)

in a field of knowledge or inquiry. In the case of JRP, which

is a transdisciplinary journal aiming to help researchers

share their research experiences and learn from them, it

is particularly challenging to develop such a research dictionary

and underlying system of classification, given that there is

such a wide range of interests and activities that may be pursued

in the name and spirit of research. Trying to achieve completeness

is neither feasible nor meaningful. What is feasible and meaningful,

however, is to strive for a conceptual network that assists

its users in systematically exploring and thinking through a

certain research interest, project, or experience, or the way

they report and reflect on such an experience in a planned submission

to the journal.

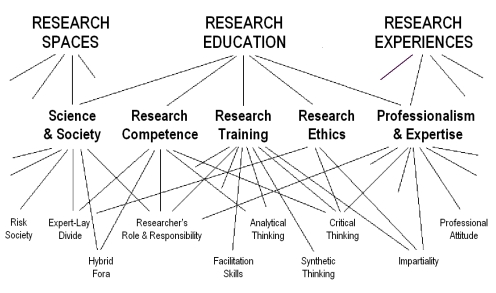

The

three levels: The

framework's three conceptual levels stand for three kinds of

concepts to which we refer, in a top-down perspective, as focus

areas, subject areas, and keywords (Fig. 1):

|

Focus

Areas

|

|

Subject

Areas

|

|

Keywords

|

Fig.

1: A three-level concept hierarchy for research

Focus

areas stand for broad topics of particular interest in which

the journal aims to be strong and which it considers to be of

key importance for reflecting about research practice. To put

it differently, they mirror the core questions on which the

journal aims to focus as a platform for discussing research

practice. Accordingly, the focus areas are defined by characteristic

core questions along with a limited number of subject areas

assigned to them.

Subject

areas stand for more specific (but still fairly broad) issues

that such discussion may raise, for example, concerning notions

of research competence and training, or the institutional and

societal contexts within which researchers work, or the basic

methodological frameworks and paradigms they rely on. Subject

areas are described by an open-ended number of keywords assigned

to them. Not all subject areas need to be and currently are

constitutive of focus areas; some may be assigned to several

focus areas.

Keywords,

finally, are basic terms for describing the nature and content

of specific research projects or papers. There is no such thing

as a definitive or complete list of keywords. The list of keywords

assigned to each subject area will need to grow and to be continuously

be adapted to the development of that subject area, its changing

topics of central interest as well as its changing language.

This is why we consider the concept hierarchy as merely an initial

version, the beginning rather than the end of an effort that

we hope will become a collective effort of all those

interested in it and contributing to the journal.

In

its initial Version 1.0, the concept hierarchy consists of 6

focus areas, 41 subject areas (of which 30 are constitutive

of focus areas), and around 5,800 keywords. We refer to all

these entries as index terms, a general term that offers

itself as all three levels of concepts can be used for purposes

of indexing articles.

The

network structure: Depending on whether one

looks

at the concept hierarchy from a bottom-up or top-down perspective, its entries lend themselves

to searching for the "parent concepts" or "child concepts"

that are related to some initial concept of interest. Say, you

start with an interest in "research competence" as

your initial concept. A related parent concept will then

be "research education" and a related child concept

will be "researcher's role & responsibility" (see

Fig. 2).

Fig.

2: Example of a concept family taken from the JRP concept

hierarchy

(Source: Ulrich and Dash, 2011, p. 6).

In

this example our initial concept (research competence) belongs

to the middle level, so we take it to stand for a subject area.

Accordingly the mentioned parent concept (research education)

represents a focus area and the mentioned child concept (researcher's

role & responsibility) a keyword. Further, via related parent

concepts or children concepts, one may also identify and explore relevant

sister concepts (or siblings) of the initial concept (e.g.,

in this case, all the middle-level concepts shown in Fig. 2).

Concepts

offered at the lower two levels may, in addition, stand for

cross-references to other parent concepts (i.e., other

subject areas or focus areas) where more lower-level concepts

of related interest

(siblings and/or children

concepts, in the example: subject areas and assigned keywords) can be found. In the

example, "researcher's role & responsibility"

is a child concept not only of the subject area "research

competence" but also of the subject area "professionalism

& expertise." Accordingly the index terms entered under

"research competence" include a cross-reference to

the alternative subject area "professionalism & expertise."

To distinguish such cross-references from other index terms,

they are listed in italics. This simple feature enables users

to systematically explore conceptual family relationships that

go beyond the search for parent concepts, or for child concepts

or siblings, and may include conceptual aunts and uncles, cousins,

nieces or nephews as it were. The concept hierarchy thus allows

being used as a conceptual network rather than a conceptual

tree only; one may start anywhere and can then move up or down

and laterally in all directions.

Three

main tools: So

much for a brief introduction. Should I have raised your interest,

I invite you to visit the Journal

of Research Practice, which is available on-line in

the open-access mode. You will find there three basic resources

to consult:

- an

Editorial

that explains the aims, construction, and intended uses

of the JRP Concept Hierarchy (Ulrich and Dash, 2011);

- an

overview of the JRP

Focus Areas; and

- the

initial list of the JRP

Subject Areas and Keywords (with currently some

5,800 entries)

There

is an entry

page to the Concept Hierarchy in which you can find the

above three links. Further, the overview of the JRP Focus Areas

is also presented in the Editorial, and a compact version of

it can be found in the JRP

index or "Home" page, conforming to the aim of

defining and communicating the journal's thematic priorities

and profile.

Application:

The concept hierarchy has several basic uses and expected

benefits for the journal and all its contributors and readers:

- Guidance

to authors: Starting with the focus areas and considering

corresponding core questions and subject areas, potential

authors can henceforth make a quick initial assessment

whether a contribution they envisage may be relevant

to JRP. Likewise, working their way through the concept

hierarchy may help them in structuring an article

well.

- Indexing

system: Index terms can be drawn from

all three levels of the concept hierarchy. By means

of a balanced selection of index terms from the three

levels, submitting authors can systematically indicate

to JRP editors and reviewers what they see as the paper's

relevance to the journal; conversely, the editors and

reviewers can better assess a paper's aims and relevance

and thus also can better assist the authors.

- Visibility

of journal content: A systematic choice of index

terms will do much to make sure a paper finds its target

audience. It matters in this context that index terms

drawn from the concept hierarchy will from now on be

indicated not only in the published articles as they

appear to readers (either in HTML or in PDF format)

but will also be included in the paper's metadata, that

is, that is, in the electronic data set that is not

visible to readers but which search engines may use

for identifying content. All potential readers, whether

they are aware of the Journal of Research Practice

or not, will thus have a greater chance of finding,

by means of a simple Internet search, material of interest

to them in JRP. This will increase the visibility of

published papers in the global research community.

In addition, JRP readers will also be able to search

the journal's content more systematically from within

the journal's web site.

- Editorial

tool: The journal's editorial staff and reviewers

can refer to the concept hierarchy for the purpose of

thinking through any topic with regard to its potential

relevance to JRP. Actual submissions can be assessed

more easily as to their relevance. Connections of a

paper's subject matter with other subjects that the

journal aims to cover can be explored systematically.

Options for developing a paper or for suggesting additional

contributions may thus be identified. Finally, the journal's

editors and staff can use the concept hierarchy, and

particularly the table of the JRP Focus Areas, as

a basis for taking well-considered staffing and policy

decisions.

For example,

we intend to nominate new members of the editorial team

so as to bring in specific qualifications regarding

defined focus and/or subject areas. We may also design

special issues so as to cover focus and subject areas

that have remained underrepresented in the journal.

Or, as a third and final example, we may periodically

review the journal's aims and scope by redefining the

JRP Focus Areas so as to keep pace with new insights

and issues in the quest for good research practice.

- Increasing

the over-all visibility and profile of JRP:

Indirectly, all the previous uses of the concept hierarchy

should also strengthen the journal's visibility and

profile. If potential authors can better assess how

to prepare relevant submissions; if reviewers have a

better basis for assessing a submission's relevance

and potential; if the journal thus ultimately publishes

articles that are focused on well-defined aspects of

research practice; if the journal's editorial staff

includes an increasing number of research scholars and

practitioners with a well-defined and recognized profile

in some of the journal's focus and subject areas; if

due to the journal's thus-increased profile the quality

of what it publishes grows further; and finally, if

potential readers worldwide, thanks to systematic indexing, have

higher chances to find material of interest to them

in JRP – all these factors should in the end make sure

that the journal's quality and reputation can grow,

which in turn should allow it to secure the collaboration

of qualified researchers and to generate a regular influx

of high-quality submissions.

In

addition to these expected benefits for the journal, it is an

equally important aim of the concept hierarchy to serve the

global research community:

- Offering

the research community a general taxonomy of research

practice: Everyone is free to use the JRP concept

hierarchy in whatever ways they find useful, regardless

of whether or not the aim is contributing to the journal.

Our hope is that many researchers will indeed find it

useful to use the concept hierarchy as a framework for purposes

such as

– structuring a research project;

– designing

or assessing a research report; and

– reviewing

or revising a research paper.

Perhaps

some of the users will then also decide to contribute

to the framework's further development, by communicating

to the JRP editors omissions they observe or suggestions

they may have for enriching the concept hierarchy and

improving its usefulness. The aim must be that over

time, the JRP concept hierarchy becomes a tool that

its users own and continuously help to develop.

I

therefore invite you to feel free and adopt the JRP

Focus Areas for your personal use, regardless of

whether you plan to contribute to the journal. Use it

as a tool for structuring and thinking through, within

the context of your research work, the rich and complex

issues of research that together make up "research

practice."

Outlook:

To be sure, the concept hierarchy that is available today represents

an initial version; as the Editorial introduction mentioned

above makes quite clear, the task of developing the framework

beyond its initial stage must be understood as a collaborative

project for which we depend on interested users (see particularly

Section 6 of the Editorial). Further, it is a never-ending task,

as the framework will always need to be adapted periodically

to the on-going development of research practices in different

fields.

A

second major development that we envisage is an interactive

graphic interface for displaying and exploring the concept hierarchy.

The electronic journal management platform that JRP's publisher

employs does not currently allow us to implement such a feature.

It remains a challenge for the mid- or longer-term future; for

more discussion, see again the Editorial (Section 5).

In

any case, an initial version is necessarily imperfect; what

matters more than perfection for the present undertaking is

that an impetus be given towards a richer understanding and

practice of research. Today, it is still common to conceive

of one's research and assess its quality in terms of theoretical

and methodological issues only, rather than in terms of both

research theory and research practice. The research community

can only gain by deepening its interest in, and understanding

of, the role of research practice as a force that shapes virtually

all aspects of research – from the research interests and questions

that motivate a research effort to the way the research context

is understood; from the research methods and procedures that

are chosen to the ways they are applied; and ultimately, from

the findings and conclusions that are identified to the way

they are interpreted, validated, communicated, and put into

practice.

Making

it a personal habit to question one's research proposals, projects,

and products in terms of both research theory and practice is

not a bad idea. It can mark a major step forward in a researcher's

individual quest for research competence.

I

wish you good research practice.

Conclusion

– two invitations Before

you now move on to exploring the Journal

of Research Practice (if you have not already done so,

I suggest you begin with the JRP

Focus Areas), allow me to end this Bimonthly with

these two invitations:

- An

invitation to contribute to the Journal of Research

Practice: The fact that you are

reading this Bimonthly and perhaps even are a

regular visitor of my home page may mean that you have

interests similar to mine. If this is so, you may also

be interested in topics that are of interest to JRP.

I would like to invite you, therefore, to visit the

journal's site and consider contributing to it. See

the journal's page "Contributors"

for a brief outline of the different ways in which you

can contribute. To be sure, the best way to contribute

is by submitting articles for publication (use the on-line

upload facility to this end). Thanks to its quality-conscious

but efficient and supportive peer-review system, JRP

provides an excellent opportunity for sharing your research

experiences and reflections with other researchers or

professionals and to see your contributions published

rather rapidly.

To avoid

a possible misunderstanding, the sometimes rather philosophical

character of my Bimonthly essays should not have

you assume that only philosophically oriented papers

will be considered for publication in JRP. Research philosophy

is only one of the journal's focus areas, as it is

only one among the many resources that can help researchers

achieve good research practice. Accordingly, it is only

one among many considerations that may help authors to achieve what really matters

for successful submissions: their self-reflective

nature. JRP is a vehicle not for reporting research

results but for reflecting on the ways they

are produced and used; on the underlying notions of "good"

research practice; and on what may be learned from specific

research experiences. These may consist in both completed

research projects or research in progress. The experiences

of novice researchers are also of interest; you need

not be an accomplished researcher to publish in JRP,

we also welcome contributions by diligent students of

research. JRP is a journal for all people who want to

learn about research as a practice, so try to

contribute by sharing your personal quest for learning

about research.

- An

invitation to participate in the next

Lugano Summer School: In the second

half of June, 2012, I will run the last planned event

in the current series of Doctoral and Postdoctoral

Summer Schools on Soft and Critical Systems Thinking,

LSS 2012. These Summer Schools pursue aims similarly

to those of my publications on reflective professional

practice, but they focus more specifically on the use

of soft and critical systems thinking as tools for improving

the participants's research or professional practice.

Soft systems thinking is represented by Peter Checkland's

(e.g., 1981, 1985; Checkland and Holwell, 2001; Checkland

and Poulter, 2006, 2010) work on Soft Systems Methodology

(SSM); critical systems thinking is represented

by my own work (e.g., 1983, 2000, 2003, 2006; Ulrich and

Reynolds, 2010) on Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH).

This is the first time

that I allow myself to draw attention to an upcoming Lugano

Summer School event in the Bimonthly, and

it will remain the only time. The exception may be justified given

that LSS 2012 offers the last opportunity ever to learn

about SSM and CSH directly from their originators, in

one and the same event. If this opportunity is of interest to you, please visit the LSS

site (see particularly the sections "Announcements"

and "Academic Program"). Also, in case you know of

other people who might be interested, I am grateful

if you draw their attention to the LSS site. Thank you.

I

sign off for this year with my very best wishes to all those

who belong to the occasional or regular visitors of my site

or who (if you are a first-time visitor) may become future faithful

visitors. Thank you for your interest, and stay well. Merry

Christmas and all the best for the year's end – see you in 2012.

W Ulrich

|

For a hyperlinked overview of all issues

of "Ulrich's Bimonthly" and the previous "Picture of the

Month" series,

see the site map

PDF file

|

|

|

References

Berger, P.L., and Luckmann, T. (1966). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the

Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY:

Doubleday.

Checkland,

P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester,

UK: Wiley.

Checkland,

P. (1985). From optimizing to learning: a development of systems

thinking for the 1990s. Journal of the Operational Research

Society, 36, No. 9, pp. 757-767.

Checkland,

P., and Holwell, S. (2001). Information, Systems, and Information

Systems: Making Sense of the Field. Chichester. UK: Wiley.

Checkland,

P., and Poulter, J. (2006). Learning for Action: A Short

Definitive Account of Soft Systems Methodology and its use for

Practitioners, Teachers and Students. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Checkland,

P., and Poulter, J. (2010). Soft systems methodology. In M. Reynolds

and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change:

A Practical Guide, London: Springer, in association with The

Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, pp. 191-242.

Popper, K.R. (1961). The Logic of Scientific Discovery.

2nd ed., New York: Basic Books (previously London: Hutchinson, 1959).

Popper, K.R. (1963). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth

of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Popper, K.R. (1972). Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary

Approach. Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

Ulrich, W. (1983).

Critical

Heuristics of Social Planning: A New Approach to Practical Philosophy. Bern,

Switzerland: Haupt (paperback reprint ed., Chichester, UK: Wiley, 1994).

Ulrich,

W. (2000). Reflective practice in the civil society:

the contribution of critically systemic thinking. Reflective Practice,

1, No. 2, pp. 247-268.

[HTML] http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/titles/14623943.asp

(restricted

access)

[PDF] http://wulrich.com/downloads/ulrich_2000a.pdf

(prepublication version).

Ulrich,

W. (2003). Beyond

methodology choice: critical systems thinking as critically systemic

discourse. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 54,

No. 4, 2003, pp. 325-342.

[HTML] http://www.palgrave-journals.com/jors/journal/v54/n4/

(restricted

access)

Ulrich,

W. (2006). Critical

pragmatism: a new approach to professional and business ethics.

In L. Zsolnai (ed.), Interdisciplinary Yearbook of

Business Ethics, Vol. I, Oxford, UK, and Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang Academic Publishers, pp. 53-85.

Ulrich,

W., and Dash, D.P. (2011). Introducing

a concept hierarchy for the Journal of Research Practice. Journal of Research Practice, 7, No. 2, Article E2

(16 November 2011).

[HTML] http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/279

Ulrich,

W., and Reynolds, M. (2010). Critical

systems heuristics. In M. Reynolds

and S. Holwell (eds.), Systems Approaches to Managing Change:

A Practical Guide, London: Springer, in association with The

Open University, Milton Keynes, UK, pp. 243-292.

|

|